Men in these occupations are hesitant to share their feelings, so Matt Domyancic builds rapport and helps them with mental health struggles.

Law enforcement personnel are 54% more likely to die by suicide than decedents with other occupations, according to a U.S. assessment published in Policing: An International Journal.

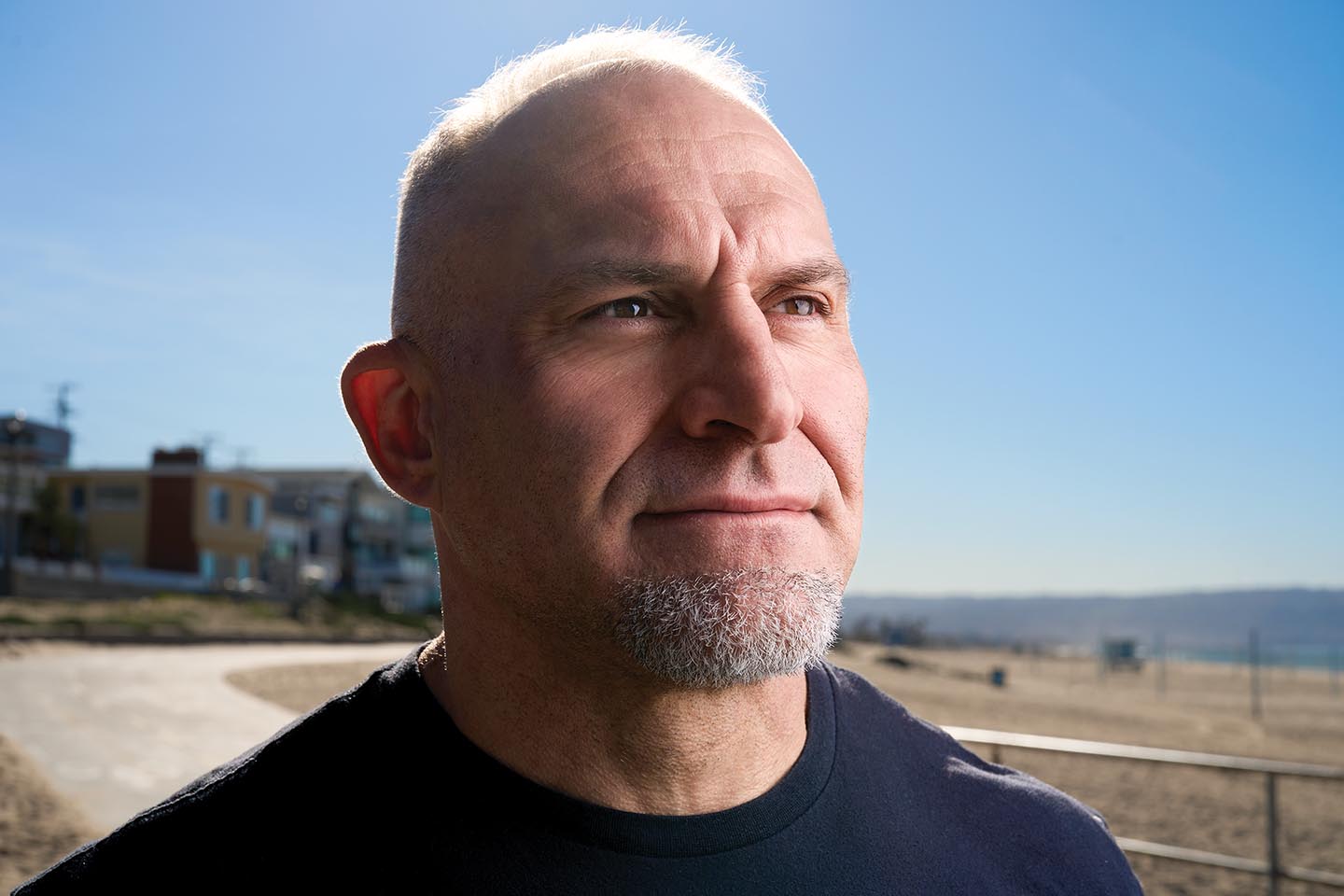

In his work as a chaplain, Matt Domyancic ’97 strives to prevent that from happening, long before it’s even considered. He likes to use the analogy of giving someone swim lessons before they’re drowning in rough waters.

“I talk to them about mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual health,” Domyancic explains.

He specializes in working with police officers, firefighters, and other first responders — occupations that have a few commonalities: high-stress routines, witnessing trauma, and a masculine culture in which expressing emotions is thought to be a sign of weakness (even for women). Because of this prevalent mindset, Domyancic builds trust and rapport by “spending time in the trenches, riding along with them on shifts, lifting weights at the stations,” he says. “And they share their stories with me.”

Officers aren’t hesitant to talk with Domyancic because they see him as one of them. It’s not a far stretch. Domyancic is a medically retired police officer who, before a botched surgery ended his career, dedicated his life to being a SWAT team member, police academy instructor, Georgetown University strength coach, and sports minister. He was living in the Washington, D.C., area and enjoying his multiple responsibilities. But after the surgery, he had medical complications, needed more surgeries, and was prescribed medications that “killed my immune, digestive, and endocrine systems,” he says. “I ended up obese, chronically ill, and I was forced to retire. I went through a very difficult period.”

A psychiatrist suggested he go to California, where a holistic approach of functional and integrative medicine was more available at the time. So in 2009, he moved to Los Angeles (where he still lives today) and spent two years building himself back up. “I had to eat clean, meditate, stretch, journal, do therapy, do neurofeedback,” he says. “It wasn’t taking a pill to get [quick] results.”

Domyancic has understood the importance of physical, mental, and spiritual health since he was a football-playing political science major at Colgate. He transferred to the University from the Air Force Academy his junior year after a cadet broke his eardrum in boxing class. Domyancic visited Harvard, Cornell, and Colgate — which he chose based on Coach Ed Argast ’78, who took a genuine interest in him beyond football and introduced him to administrators and career counselors. It also helped that there were 13 other players from Domyancic’s hometown area of Pittsburgh.

Early on, though, he had a setback: Domyancic tore his calf during practice and thought he would never run again. This led to a spiritual crisis. Raised Catholic, he’d learned about other religions when starting his college career and had a desire to learn more about other faiths. Domyancic met with the campus priest as well as professors from different religions to learn their perspectives. This was the start of a 10-year “investigation of my own,” he says. “I exposed myself to different branches of Christianity, to Buddhism, to Native American spirituality. I studied the contemplative practices and the depth psychology of different traditions because I never wanted to only serve people who think just like me.”

Domyancic earned a pastoral theology degree from Loyola Marymount University in 2018, and he began doing chaplaincy with police departments in Los Angeles. Today, he works with approximately 400 police officers and firefighters. He also receives invitations from organizations helping first responders with mental health issues around the country.

“I try the proactive approach,” he says. “A lot of times, mental health professionals and peer support are only for PTSD, addiction, and suicide. But there’s a long road to that.” By building long-term relationships with the people he helps, Domyancic finds that they’ll talk to him before a critical incident occurs.

His methods involve “normalizing therapy and improving fitness, nutrition, stress management, self-regulation — different things to holistically help people live better lives before they end up broken down.”

A linebacker, Domyancic was a member of the 1997 team that won Colgate’s first Patriot League Championship.