Matt Brogan ’05 collaborates with Massachusetts agricultural and cultural organizations to perfect traditional, dry ciders.

Nestled in North Adams, Mass., surrounded by the rolling hills of the Berkshires, there are three beautiful apple trees — right next to a Burger King drive-thru. On the median of a four-lane highway in front of a Dollar Tree, there are even more apple trees from which Matt Brogan ’05 picks for making hard cider.

There are, of course, pastoral places where he gathers fruit — including an orchard at the Herman Melville House — but Brogan has found that an idyllic setting is not required.

“It’s just hard work, getting apples from wherever you can, and turning them into something interesting,” says Brogan, who started a cidery with his wife, Katherine Hand, in 2020.

The foundations of the Berkshire Cider Project are in its name. The couple intentionally chose that area of New England, and their approach centers around the philosophy of it being a project: deliberately small, connected to the community, and open to changing ideas.

Brogan’s wife is originally from the Berkshires, so the couple would visit her family on breaks from their hectic professional lives that began in Brooklyn and then moved to Washington, D.C. He was an architectural consultant, specializing in performing arts spaces like David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center. She worked with corporations on their sustainability efforts. They’d come home and enjoy a bottle of traditional, dry cider over dinner. In 2015 she bought him a cider-making kit. “We made it, we thought we were going to bring it to a party two weeks later and we’d be the cool people with this thing we made,” Brogan recalls. “It tasted terrible.”

An art history major and physics minor who likes to “tinker with things,” Brogan didn’t just stick the kit in a closet. He set out to make a better cider. “In our tiny Brooklyn apartment, I’d have batches going: one in an ice bath, one near a window, one that had this yeast, and one that had that yeast.” A problem he identified early on was his use of store-bought juice. So, on one visit to the Berkshires, they stopped at an orchard (which they now partner with) and purchased some fresh-pressed juice.

“It really was just a hobby, but it got out of control,” Brogan says. “It took over our basement, and then suddenly I was taking a week off work to go to a cider workshop at the Cornell ag school.”

Meanwhile, his MBA-holding wife, who makes business plans for fun, was playing around with a cidery strategy. “At some point,” Brogan says, “we sort of couldn’t help ourselves.”

They saw potential in the Berkshires, “where no one was doing this kind of cider in a region that was traditionally known for its apple growing and hard cider–making,” he says. Nowadays, the area is best known for the arts, from the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art to the Tanglewood music festival and center. Brogan and Hand are marrying the past and the present, the agricultural and the cultural. “My wife calls it a love letter to the Berkshires,” he says.

They opened in 2020, finding an old wool mill that architects converted into a multiuse facility. Brogan designed their space and built its furniture. The couple operated seasonally, part time, while maintaining their jobs in D.C.

The launch wasn’t motivated by pandemic-fueled discontent, but the timing did have benefits. “That first year we were sitting on all this cider and needed help to bottle and label,” Brogan says. They found help in the artists and musicians who were suddenly no longer able to travel for work.

Other locals also offered support. As people came to buy cider, they’d bring their own apples and ask, “Can you do anything with this?” Soon, the couple hung a sign saying, “We want your apples.” It became the Community Cider Project, Brogan explains. “And it’s everything from a parent and their kid bringing us a little bucket of apples from their backyard to being invited to an old farm with 40 apple trees.” Sometimes they’re told, “You can get back there, but you’ve got to whack out the prickly bushes.” The payoff can be truckloads of fruit.

The Berkshire Cider Project also partners with commercial orchards, but interesting-tasting cider requires fruit from different locations.

“We’re not farmers, and I don’t really want to be one,” he says. “So how do we expand this idea of getting a few bushels from here and there — how do we do that at a little bigger scale?” One opportunity that’s presented itself is at Melville’s Arrowhead farm. The property manager secured a state grant and approached the couple with the desire to recreate the old orchard. They’ve planted 30 trees so far.

They just received approval to do a similar project this spring for the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival.

And they’ll soon be releasing a pear cider from fruit found at Edith Wharton’s home, The Mount. Brogan is brainstorming labels inspired by the great writer’s work.

After three years, Brogan and Hand left their previous jobs and committed to the project full time this year. They’ve outgrown the mill space — which they used as both a production facility and tasting room — and the Berkshire Cider Project is moving. Their “new” space is an old autobody shop they’ll renovate. It’s yet another exciting task for Brogan, who’s stimulated by the creative outlets in this job. Meanwhile, his scientific side dabbles in challenges like how to use quinces from local English gardens to make a sour cider.

They currently offer 13 ciders, the number being purely coincidental and hitting the maximum of what they hope to achieve. Brogan, the head cidermaker, will make approximately 3,000 gallons this year. “That’s just about as small as you can get,” he says.

Their ciders are comparable to a dry white wine or champagne — a growing trend in the industry. “We were so afraid that people were going to come in wanting sweet cider and that we were going to disappoint,” Brogan says. “We’ve had the opposite [happen]. People are so grateful because [this type of cider has] been hard to find. But luckily people now know what it is. You just have to find it the right way.”

And sometimes, that right way begins near a fast-food drive-thru.

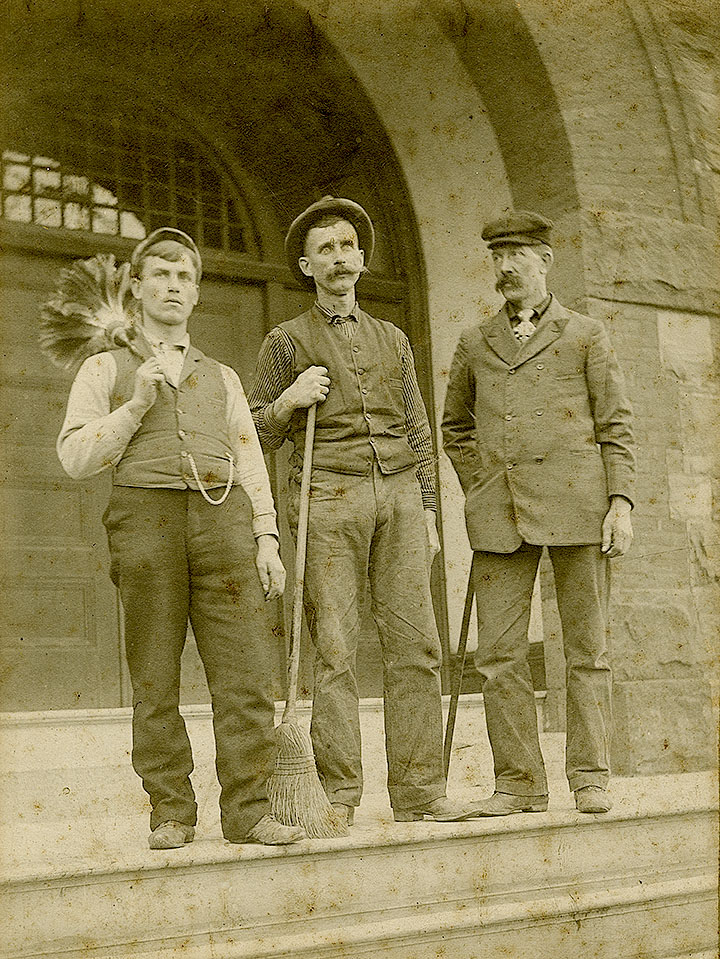

Brogan’s great-great-grandfather was Lant Gilmartin (pictured, center), who worked at Colgate in the late1800s. His title was head janitor, but the University history books explain that he was so much more, serving as the right-hand man of James Taylor, Class of 1867. Gilmartin supervised the crew of fellow Irish immigrants digging Taylor Lake. “There is one style of work which money cannot buy and dollars can never pay for, and that is the manner of work which Lant gives Colgate,” said a Madisonensis writer, quoted in Becoming Colgate. Photo courtesy of Special Collections and University Archives.