Aug. 31, 1931–May 4, 2022

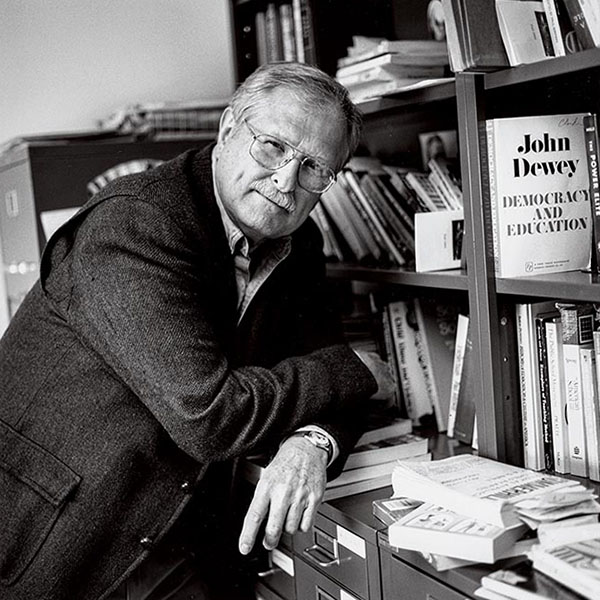

James E. Clarke, professor of education and social science emeritus, was ahead of his time in many ways, from his approach to his field to his beliefs about inclusivity.

He wasn’t just a staunch supporter of Colgate becoming a coeducational institution in 1970; when the women students arrived, he also encouraged them in their academic endeavors and bolstered their self-esteem.

“He built [my] confidence in my ability to analyze and think things through,” remembers Deborah (Booker) ’74 Matthews, who, as one of the first Black women students at Colgate, faced discrimination by some professors.

Cozette (Rooney) ’74 Ferron credits Clarke with “saving” her education because she hoped to major in educational studies at a time when that concentration wasn’t offered at the University. Clarke developed the major and created internship opportunities for students at local schools.

Clarke inherited his love of education from his mother, who taught in a one-room schoolhouse in North Dakota, where he was born. He earned his degrees in education and social sciences: a BA from Ithaca College and his MA and PhD from Cornell University. When he joined the Colgate faculty in 1962, he was finishing his PhD. “I was thrilled to be here,” he said in a 2020 interview with Colgate Magazine. “I felt quite welcome.

“I wanted to go to a place where I could establish an idea, and that was the idea that we should have a widespread analysis of education from a liberal arts perspective.”

Clarke and some of his colleagues set out to persuade “a very large body of the liberal arts family” to adopt the educational studies major, he recalled. It was, Clarke said, “a friendly revolution at Colgate.” He later led the development of a master of arts in teaching.

While most educational studies programs at the time focused on simply training students to become teachers, at Colgate, Clarke adhered to a different approach. He wanted his students to understand institutions, processes, theories, and a global perspective. “It was much more theoretical, which is the basis of the liberal arts,” he said.

Ferron remembers: “He was the one who really had me thinking out of the box.” She recalls learning from him the philosophy of teaching and “creating a utopia where everyone participates.” Clarke stressed an inclusiveness theory, she adds, which fostered her own beliefs that led to a career in special education.

Clarke’s other accomplishments at Colgate included a Ford Foundation Grant (1968), through which he and his family traveled the world studying in many countries. He also was the adviser to the women’s soccer team and the Kappa Delta Rho fraternity. He retired from the University in 1996.

Clarke is survived by his wife of 49 years, Donna; three children; three grandchildren; and his brother-in-law.