Colgate Magazine learned about the work of Bruce Morser ’76 when we heard about his commission to draw the Mars Rover for National Geographic. For our autumn issue, we hired Morser to create portraits of two alumni who discuss the science of snacks. Here’s what he had to say about his process and his work:

“I get to draw somewhere between 50 to 100 portraits a year. It’s a fun change from the stuff I usually do.”

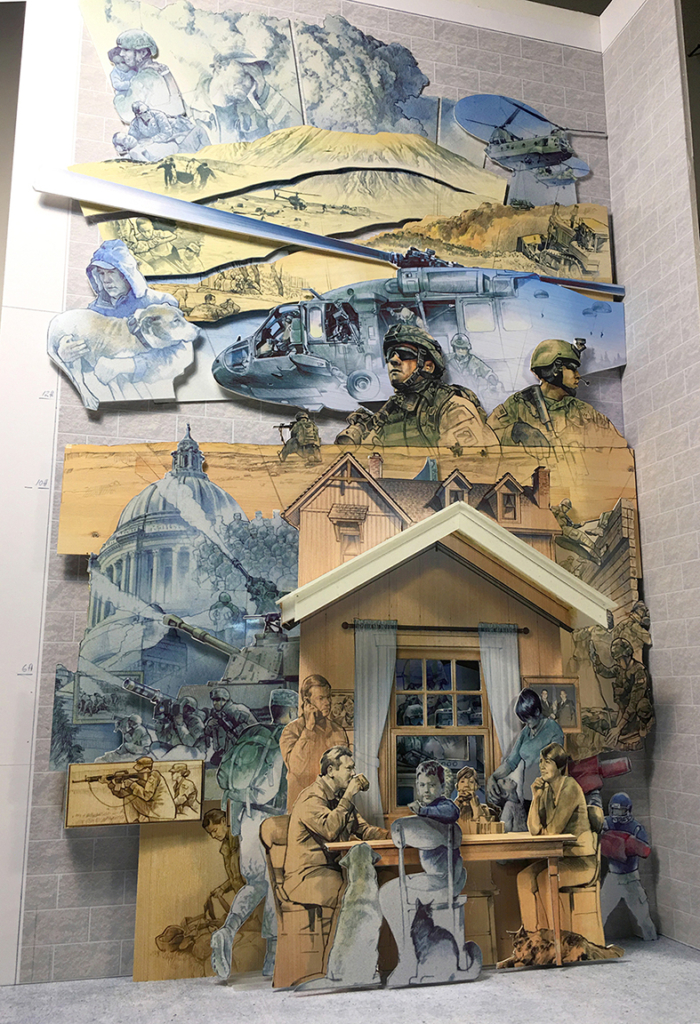

“Lately, I make and draw big installations for organizations. I’m working on one now for the National Guard; it’s about 25 feet tall and 15 feet wide. I make things out of a combination of wood and acrylic panel. [It will go] in a facility in Olympia, Wash., where there’s a new readiness center. It will be their big entry piece to try to help the public understand this greater role of the National Guard.”

“One of the things I really like to do is engineer things, and I like to figure out, so that’s going to be a couple thousand pounds and it’s 25 feet tall. How does it not fall on somebody? I really liked figuring that out and how to attach it to a wall. I’ve always enjoyed combining those two things.”

“I worked as an art director out of college for a couple of different advertising agencies and eventually for Leo Burnett in Chicago. I was a fine art major at Colgate, so it seemed like, I’m not really doing what I’m supposed to be doing. A couple people gave me the courage to go off and make imagery. I went back and got an MFA in painting [at the University of Washington].”

“There’s no retirement. These things are so interesting to make and so challenging that I can’t ever see stopping.”

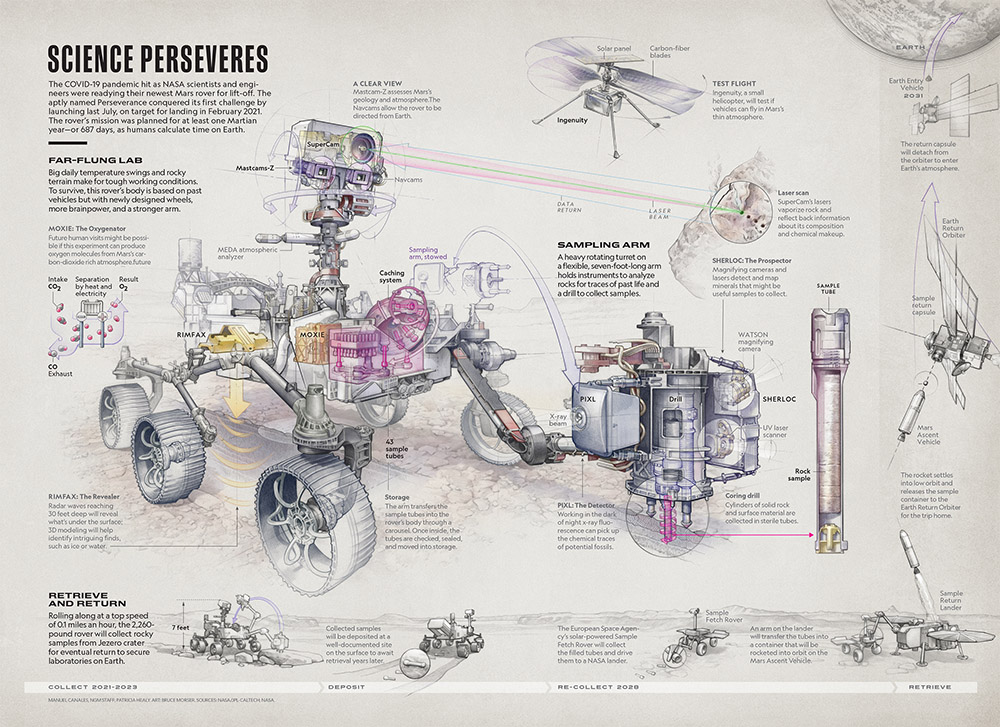

“In 45 years of doing this, one of the really cool things is I’ve never had a single boss; I have several bosses every year. It’s like perpetually being in a 101-level college class because you show up the first day and they throw you this information. The techniques I learned in college have [helped] … putting all this stuff up in your head for a time to be able to gather, use it. That’s exactly what these jobs are like… Martian Rover — that one took me about two months to figure it all out and make the imagery. I had to learn a great deal about Martian Rover. It’s like I’ve taken hundreds and hundreds of freshman level classes in my life. It’s cool.”

“One of the challenges of what I do for a living is … when you make imagery, you have to sit alone and do it. So I’ve always had to work things that would bring me into community situations. So I teach — the age range is huge, from fourth grade to 80-year-olds — in Seattle. I teach how to draw, but it’s more like using drawing as a way to access greater creativity. It’s not really about making the drawings. It’s about finding the ability to really see the world.”

“The key [to making portraits] is — and this is what I teach too — when I start drawing, I know that likeness is important, but that somebody needs more than a likeness, they need a feeling. What I’ve learned to do is I’m very unaware that I’m drawing a face. And I become utterly aware of the visual pattern that [faces] make. If I can stay true to being aware of that pattern, that seems to unlock a greater ability to communicate who [the subjects] are. We tend to look at something like a face and do this recognition, like two eyes, eyebrows. We jump on those as items that you put together, like you would with words in a sentence. And that tends to make things too much the same or categorized. When I’m purely looking at pattern, I am reducing everything to just what’s light, what’s dark, what’s green, what’s red. And seeing how those things flow to one another, I drop all the preconceived kind of symbols, and that seems to really help…. If you can capture that, then that somehow triggers in the viewer some sort of response; it’s much more connected to an emotional side. And I think that’s important.”