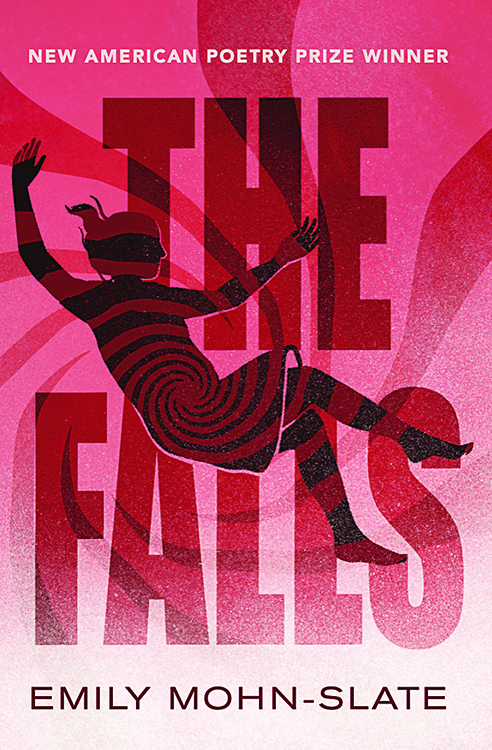

In her prize-winning new book, The Falls, Emily Mohn-Slate ’01

dives into the complexity of emotions.

Finding and holding on to happiness, gratitude, contentment — the bundle of feelings that describe joy — in the midst of hardship is a struggle everyone can relate to after this past year. Emily Mohn-Slate ’01 wrote the poem featured here before the pandemic, but its sentiment is evergreen.

She was inspired by fellow poet Ross Gay’s book, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude — both the themes he explores and his narrative writing style. Mohn-Slate approaches her own poetry by finding inspiration in real-life events and using them as a jumping-off point into her creative realm.

“I was doing my version of the logic of his poems, where you’re thinking about one thing and then you leap to another idea or thought,” she says, “which I think mimics the way our minds operate.”

At the time, Mohn-Slate was a new mother, so she wrote about grappling with the uncertainty of the future as well as the idea of mortality. “In the end of the poem, the speaker gets to this realization that joy is so bound up with loss and with how finite we all are — that the depth of the joy we experience connects to the fact that our lives will not go on forever,” she says.

While the piece keeps slipping back into sorrow, sadness, and grief, the speaker keeps wresting it back to joy, she explains. “And then it ends on a note that contains all of those emotions mixed up together.”

The poet was battling these conflicted feelings herself as she was quite literally trying to write a joyful poem. She estimates that it took 50-something drafts until she was satisfied.

Mohn-Slate spends a lot of time talking about the writing process in her high school English classes at Winchester Thurston as well as in the Madwoman in the Attic Writing Workshops she teaches through Carlow University.

At Colgate, Mohn-Slate was an English major who took poetry courses, including one with Peter Balakian, the Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar Professor in humanities and professor of English. “I learned so much from him,” she says. In her junior year, Mohn-Slate took Professor (now emerita) Margaret Darby’s literature course on language and gender, which gave her a new perspective: “I started reading all these feminist poets who completely blew everything open for me, and I thought, ‘I want to write my own stuff. I don’t want to only talk about what other people are writing.’”

She went on to earn her master’s at Boston University and spent several years working at Carnegie Mellon University. Approximately 10 years ago, she returned to that goal of writing her own poetry and essays. A few life changes and many drafts later, The Falls was published in 2020 and received the New American Poetry Prize. The book’s final chapter concludes with “I Am Trying to Write a Joyful Poem.”

“When you’re ordering a book of poems, it’s like making a playlist; you want your first and last poems to have a lot of impact on the reader,” she says. “And what I wanted, for the narrative arc of the book, is for the reader to feel the speaker trying to move toward the light.” There are somber notes in The Falls, which deals with divorce, the anxiety of motherhood, and death. Even so, the book is not depressing; it’s a portrait of life. And while “it’s not a happy ending,” Mohn-Slate says, “it’s at least trying to be a happy ending.”

Next, she’ll be writing new poems that explore the ways technology affects relationships. “I started working on these poems before the pandemic, and now [the topic] feels even more relevant, given how many of our daily social interactions happen online,” she says. The poet will observe how technology hampers our ability to be present for each other, changes our relationships as well as our ideas of ourselves, and creates connections but also disconnections.

I’M TRYING TO WRITE A JOYFUL POEM

after reading Ross Gay’s new

book,

which makes me feel light

and giddy, like maybe

a world in which figs fall

from a city sky is possible,

but my poem becomes

about the collapse of long

love, how even the brightest

glint in the eye

becomes shadow eventually.

My son dances across

the room in a red

cowboy hat, he asks me

to chase him,

but the girl in the documentary

I watch lives in a landfill

outside Moscow —

she drinks water from

dirty milk jugs and —

why does joy always slide

into darkness?

My son laughs, his eight teeth

new and white, shining in the

sun

while I tickle his belly.

Joy must be at least

as complicated as sorrow,

which is one reason

I hate those posed pictures

people take before

weddings, before babies,

hands clasped over the

woman’s

belly — cupping warm skin

thinking they know

what’s inside.

Maybe joy is an animal that

scurries

when you get close,

or maybe it’s my son

pointing out the moon

saying Look! Up there!

which makes me think

how he almost wasn’t

so many times.

And doesn’t the girl in Moscow,

Yula is her name,

have joys, too?

And this cramped coffee shop

hums with people telling

other people across a stretch

of table what it feels like

to live on this planet right now,

to have a mouth,

to form words — I’m saying,

How are you feeling?

She’s saying, It was just so

funny,

so damn funny

and the woman next to me

she laughs, she sighs,

she holds her belly.

Maybe joy is the real mystery.

Maybe I’ve been wrong

for decades, only looking

under the rock, pointing out

the shades of dark.

Last night I lay across

from my love and

said I love you,

something I usually say

while opening the fridge,

while leaving the house,

my back turned,

I said I love you

staring right into

his open eyes —

what made me look

is that I remembered

he will die. Maybe joy

is a hand reaching out

in a fierce wind,

one so very hard

to open your fingers in,

or your eyes.

5-Minute Poetry Class

“Read a lot of poetry … a lot of different kinds of voices so that [you’re] not only reading poems by people who live in the world in different contexts and ways, but also seeing different ways to make a poem.”

“A lot of people come into studying poetry with negative associations like it has to rhyme or have hidden meanings. [Some] people feel like they can’t fully access poetry as an art form. I love breaking down those barriers and finding ways that each person feels like they’re able to connect and respond to voices that speak to them.”

“It’s not that you have to find a voice. Everybody has a voice already. It’s how you are going to claim it and use it to articulate what you want to say.”

“Don’t fall in love with your poems too quickly. Once you have a full draft, force yourself to reconsider the poem again. In poetry, even small changes can have a big impact.”

“Your first draft can and should be absolutely terrible. You might end up with a couple of good lines in there, or even a couple of stances if the muse is kind to you, but a lot of times, it’s a process of unfolding the idea you’re wrestling with. Turn it over in your head when you’re driving to work, or in the shower, or making dinner.”