Margaret Perez Brower ’11 writes about how a more equitable system can be achieved through intersectionality.

In 1996 Mariella Batista, a Cuban immigrant, was afraid for her life when she asked for a protection order against her estranged partner who had abused her for years. Legal Services Corp. (LSC), a federally funded nonprofit, rejected her appeal because LSC could not assist anyone who was not a citizen or lawful permanent resident. A week after her request was denied, Batista was fatally shot by the man in front of their 9-year-old son as they were heading into a Riverside, Calif., courthouse for a child custody hearing.

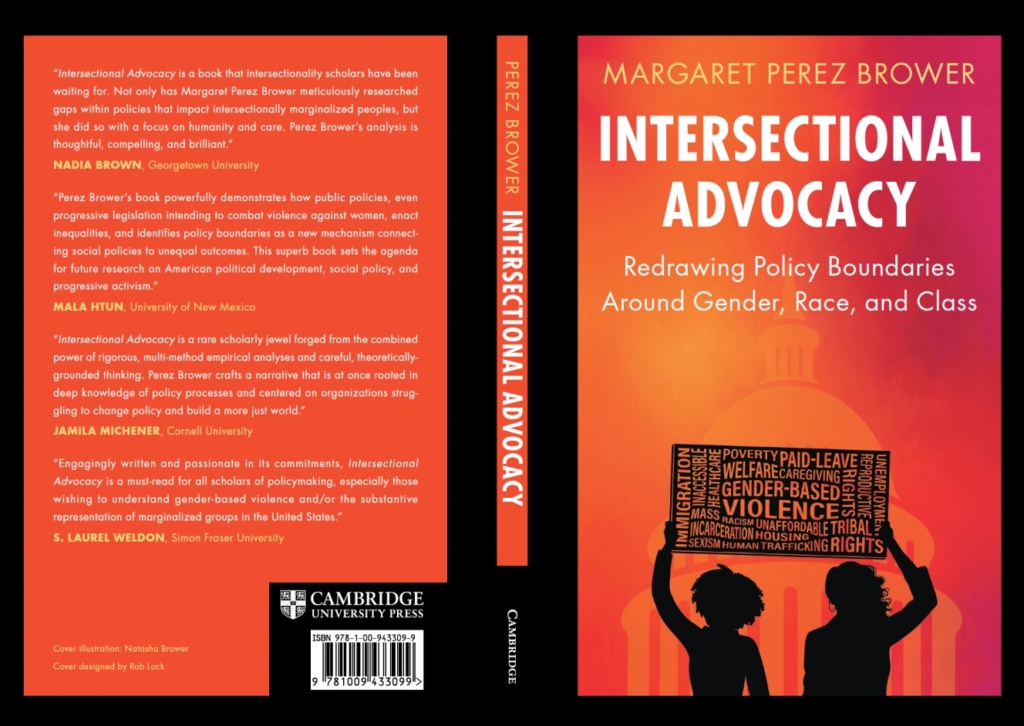

What happened to Batista “illuminates what policy gaps do to people who are marginalized,” says Margaret Perez Brower ’11, who tells the story in her new book, Intersectional Advocacy: Redrawing Policy Boundaries Around Gender, Race, and Class (Cambridge University Press, 2024). The book shines a light on activist groups that are “changing how we think about public policy [by] linking together issues like gender- based violence, housing, immigration, mass incarceration, and health care,” Perez Brower explains. “Millions of people are affected by more than one of these issues at the same time, so by linking these issues together, these advocacy groups are helping us have a policy system that comprehensively and holistically is taking care of people.”

Perez Brower’s book comes from her award-winning dissertation at the University of Chicago. After a two-year postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard’s Inequality in America Initiative, she joined the University of Washington in fall 2023 as an assistant professor of political science and gender, women, and sexuality studies. Her teaching is inspired by the late Colgate professor Joseph Wagner, who taught political science and helped develop what is today called the Office of Undergraduate Studies (OUS) program.

Participating in OUS “was an entryway for me to get an amazing educational experience,” says Perez Brower. And because she was interested in assessing how programs work, Perez Brower received a stipend during her junior year to support a summer research project for which she conducted interviews with OUS students and staff members. “It was giving back to a community I cared deeply about, and it put me on a trajectory of thinking about how research can do really important things,” adds Perez Brower, who majored in political science and educational studies. “Even for programs that you love, [research] can help transform them and make them better. And that really stuck with me, so I don’t think it’s surprising that I wrote a book about advocacy groups that are similarly doing empowering things.”

More from Perez Brower:

I’ve been thinking about intersectionality since I became aware of how my experiences mapped onto my identity as a woman of color living in this world. Intersectionality is something I personally experience, and that I see people in my community and my family experiencing.

When you’re a first-generation college student, you become aware of how much there are these systems, these benefits that are pretty exclusive. I learned at a very young age that certain people are just more prepared and supported to thrive. When I was at Colgate, I felt incredibly grateful to have access to that world because I realized I would be able to do important and powerful things.

[OUS] was a structure in which I could empathize and connect with other students who were people of color, first- generation, [and/or] low-income. We move through this world, sometimes a little bit lonely, not knowing if our experiences are similar to others’. Having that sense of community was really important to me.

[In the book] I look at organizations across geography and different policy spaces. Some of them are working at a federal level through places like congressional hearings, others are working at a state level in state coalitions, and then there are local advocacy groups. These activist groups are shaping public policy in a transformative way that is better for democracy if we care about justice, equity, and fairness.

It was my hope that I could write a book that would be rigorous and have empirical evidence, but that someone like my mother or my sister, who aren’t in academia, could understand and use. There is also a lot in there for organizations — how they could support intersectional advocacy. And then I also have some guides for policymakers.

My [forthcoming] book is about the COVID-19 pandemic, but also recessions in general. When you have something like the COVID-19 pandemic — which was a particular type of recession and shock to the retail, hospitality, and food service industries — how do the most vulnerable workers get affected? And what role does the government play? Since the Great Depression, the government has been doing these relief policies, which are supposed to help people most in need. What we’re trying to do (I’m working on this project with Jamila Michener at Cornell University) is figure out, to what extent do [these relief policies] reach the most vulnerable workers? I’ve been conducting interviews with women across race and ethnicity to learn about their experiences.

I see academia as a powerful tool because it gives you this language, these concepts, these research tools to be able to take lived experiences and amplify them, make them visible, understand them in ways that make intersectionality not necessarily a marginalized experience, but something that could be more empowering for people. I wouldn’t do this work if I didn’t think it had the potential to actually change systems of inequality and long-standing forms of oppression.