An unwavering curiosity becomes a labor-of-love project for Peter Oltchick ’91.

I couldn’t not open the box in my mother-in-law’s basement.

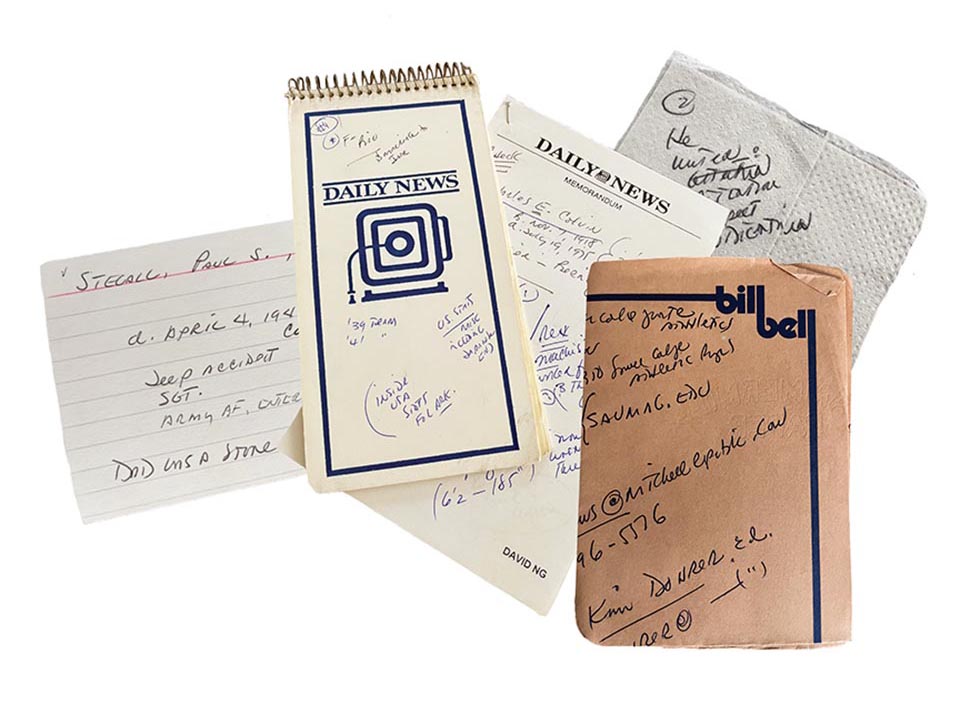

Inside was a perfect mess of my late father-in-law’s book research: chicken-scratch scribbles across mounds of cocktail napkins, backs of envelopes, bits of small sheets — including remnants of an amorously illustrated à faire aujourd’hui (to do today) notepad, scattered index cards, sectioned thick spirals (via fraying Post-it notes), and of course, his trusty 8″ by 4″ Daily News notebooks.

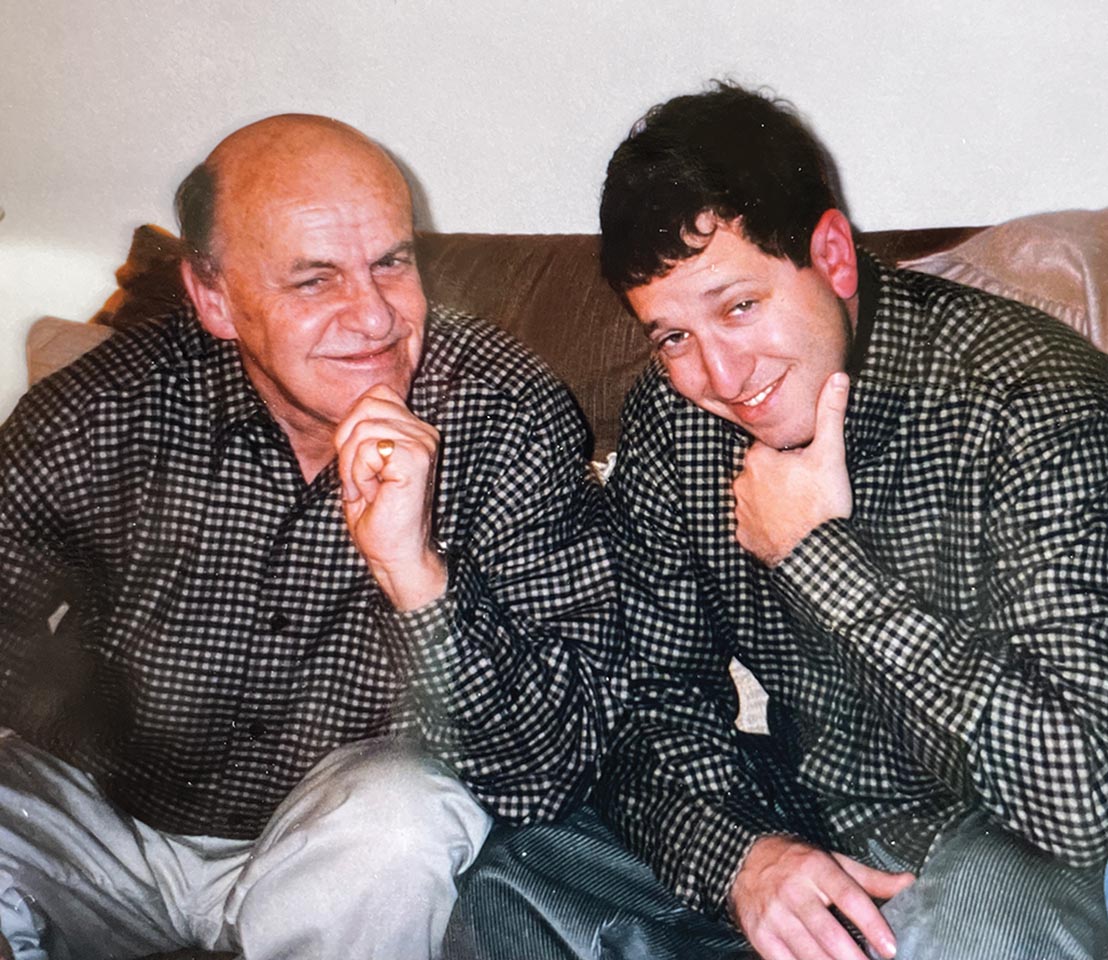

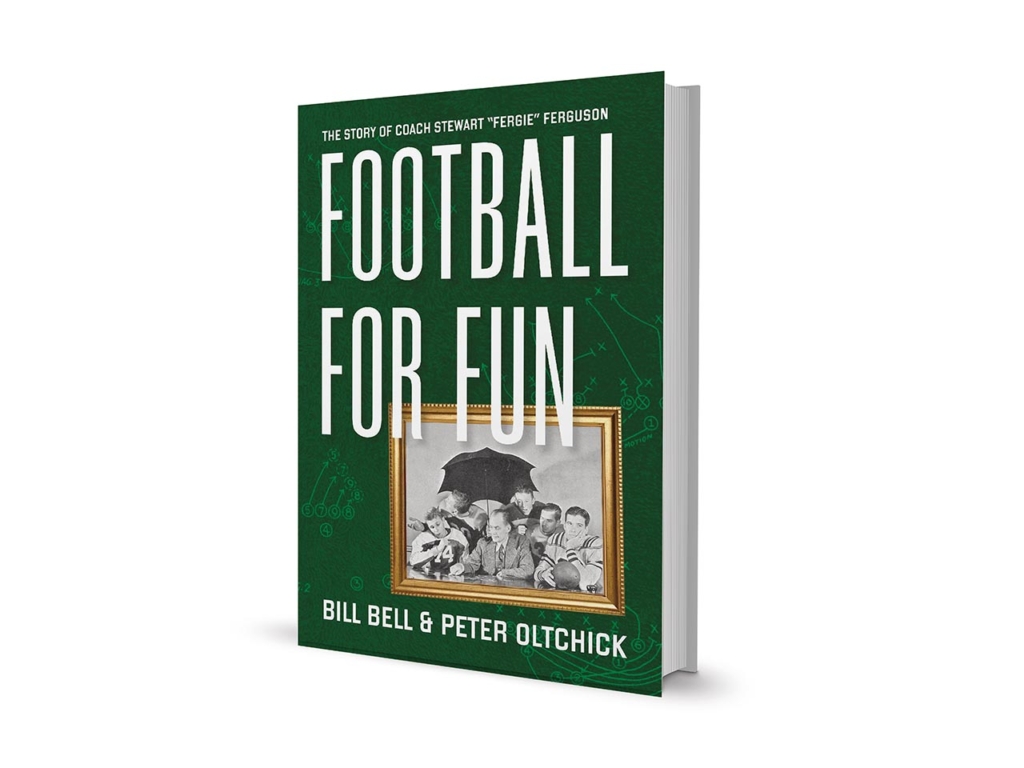

An acclaimed lifelong journalist who grew up in Pine Bluff, Ark., Bill Bell had worked extensively on a book about a nutty, rural Arkansas college football team (the Arkansas A & M Boll Weevils) with a strange sort of coach, who from 1939–41 had become famous, and in certain circles infamous, for playing and losing — from coast to coast — for fun. However, Bill and his literary agent increasingly pictured a bigger book, one centered on a slight, mild-mannered but fiery ex-college coach turned full-time history teacher. The hard-to-fathom story of Coach Stewart Ferguson — later known as “Fergie” — was in motion. Battling failing health, Bill would make a strong push to capture Coach Ferguson’s turbulent and defining earlier years.

Upon scanning several of Bill’s chapter files, I, too, was hooked by the fascinating Fergie and felt a strong pull to shape the book into a biography. I was especially energized to dig into Fergie’s later years, in which he, as a high school football coach, left an indelible imprint on the Black Hills’ still frontier town and close-knit community of Deadwood. I reset to full-research mode, channeled my days as sportswriter and editor of the Colgate Maroon (pre 1992 merger with the Colgate Snooze [couldn’t resist]) and went about trying to walk in Bill’s — and Fergie’s — footsteps, which led me to Arkansas, Louisiana, and across South Dakota.

As for the whole writing part, I started with some simple internal marching orders: Don’t screw this up! This maybe wasn’t the most productive approach, so I pivoted to something more positive, though hardly pressure free: Do right by Bill. Not surprisingly, my overriding thoughts focused on ensuring the final manuscript would read as one voice. To address early agita around revising, moving, or deleting any of Bill’s content, I leaned on a healthy dose of color-coded fonts and annotated strikethroughs; every new draft specified what changed from the previous version. If a prospective publisher wanted the play-by-play “save as” anatomy of a manuscript, I’d be ready.

Eventually, the multicolor fonts faded, the strikethroughs disappeared, and voices evolved into voice. A spectrum of doubts shifted into a semblance of rhythm and ascending confidence. At a certain point, who wrote what was no longer a thing, which felt freeing. Writing and rewriting became solely about serving the story — sharing and celebrating Fergie’s wild ride.

Reflecting on the entire labor-of-love process, I gravitated to some narrative nonfiction guideposts that kept me on track. Holding on to the story — and character — helped me focus on Fergie’s journey and ensure the reader rooted him on through his multiple missteps.

I also slowed down when necessary and embraced all the circuitous paths of the research process, realizing that surprises and new nuggets could be around the corner. In fact, some of my favorite finds came from allowing myself to just read and learn. This was particularly true as I consumed late 1800s to early 1900s newspaper issues of the Deadwood Pioneer-Times and the Lead Daily Call and worked to understand the complex relationship — and bitter rivalry — between the twin Black Hills cities.

For interviewing Deadwood High School alumni, I ensured I was extra prepared. The due diligence around gathering old photos and accumulating football game-day details were essential triggers to spark specific decades-earlier memories and other revealing insights. Nearly as important was actively listening.

Through it all, I fought myself to perfect wherever possible but try not to demand perfection.

Approximately eight years after I peeked inside that big, dusty box, the whirlwind of feelings came roaring back when I was preparing the book’s acknowledgments. Dubbed by his family as “the thing in the basement,” Bill had the unique ability to do a crossword, play guitar, read, watch college football, belt out Johnny Cash, and nap all at the same time. Yeah, and as a lifelong newspaperman, he could also bang out stories with the best of ’em.

Those stories took Bill literally around the world for the United Press International — from South America to Europe and Africa — before he settled down in Connecticut and started up at the New York Daily News. Spending years as the religion editor and “City Beat” columnist, he was a witty, gritty, wise, and beloved newsroom figure.

While his newsroom buddies knew how excited Bill was about his second act as an author, I only became acutely aware after stumbling upon a document during some additional Connecticut basement book research. Circa 2004, Bill Bell typed up the not-so-little, therapeutic ditty It didn’t take this long to… Enjoy one of the 53-strong beauties, a nod to Fergie’s religion-centric musings in the book: “It didn’t take Adam this long to convince Eve they should be more than friends.” On Bill’s behalf, I’m thrilled the wait is finally over.

This essay by Peter Oltchick ’91 includes text from a forthcoming book by Bill Bell and Oltchick, Football for Fun: The Story of Coach Stewart “Fergie” Ferguson (South Dakota Historical Society Press, September 2023). Oltchick is also the author of the children’s picture book Clean Clara. He says 13 is indeed his lucky number, thanks to both of his kids’ birthdays (including one on Colgate Day!). He can be reached at pjo24@yahoo.com.