Paleontologist G. Arthur Cooper conducted field research in North and South America while working his way up the Smithsonian command.

Gustav Arthur Cooper, Class of 1924, MA’1926 dedicated 57 years of field research and hands-on leadership to the Smithsonian Institution. His specialized focus on Paleozoic brachiopod fossils (shelled marine organisms) unearthed the history of their evolution.

At Colgate, Cooper studied chemistry and geology. In the latter field, he stayed with the University to earn his master’s degree. In his dissertation, “Stratigraphy of the Hamilton Group of New York,” he remarked that Hamilton is “especially well-known for its abundance, beauty, and variety of fossils entombed within its mass.”

After Colgate, Cooper went on to Yale, where he delved into the study of fossil brachiopods and earned his PhD in 1929. This was also where he met his wife, Josephine Wells, who was a fellow geology student.

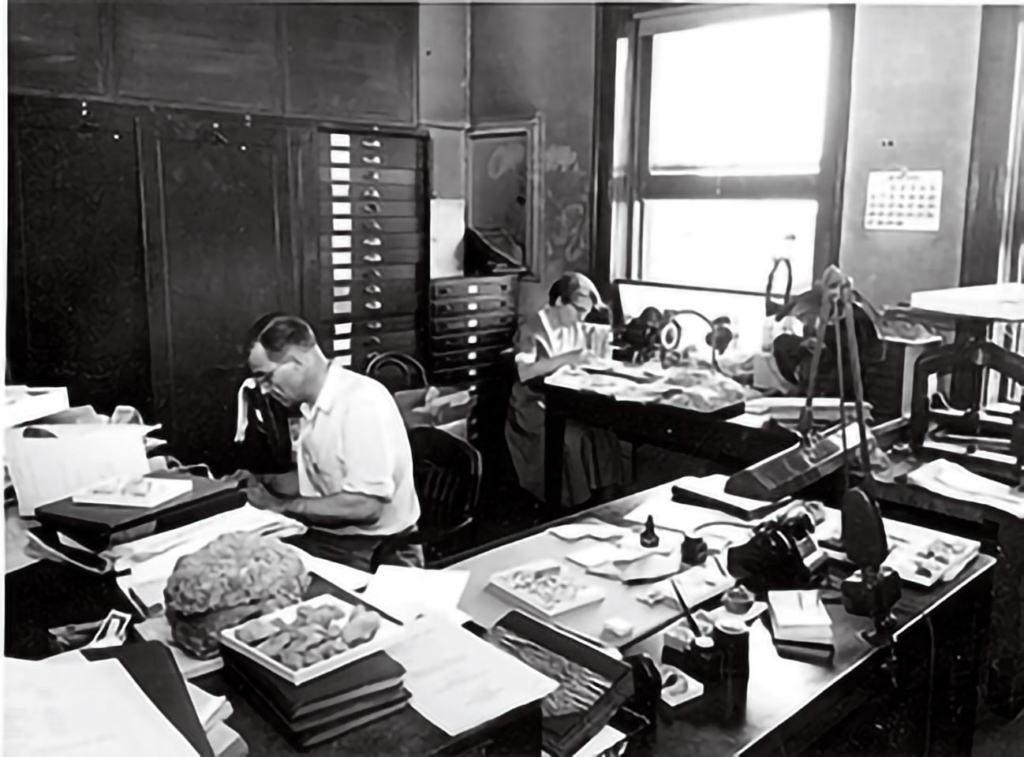

Cooper continued to unearth fossils by conducting field research in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, yearly. He was responsible for an abundance of field-defining discoveries, such as the naming of the brachiopod genus Maltaia in 1983. Along the way, Cooper worked his way up the Smithsonian command, with roles including the head curator of the Department of Geology (1957) and chairman of the Department of Paleobiology (1974). He continued his research with the Smithsonian through 1987.

The Smithsonian specimen database contains 6,475 specimen lots that Cooper collected on his own and an additional 4,242 specimen lots he collected with collaborators.

One of Cooper’s more acclaimed collaborative projects was a work he co- authored in 1938 titled “Ozarkian and Canadian Brachiopoda.” In this piece, Cooper and colleague Edward Oscar Ulrich examined the “parallel development” of brachiopods, which occurs when distinct species living in the same region evolve with similar characteristics. Cooper’s work on the matter contributed to the body of early research on parallel development and proved that organisms that live together evolve together.

For both his excellence and devotion, Cooper received the Paleontological Society Medal in 1964, the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal of the National Academy of Sciences in 1979, and the James Hall Medal of the New York State Geological Survey in 1986. In a statement released from the Paleontological Society, members Ellis Yochelson and James Thomas Dutro Jr. memorialized their colleague’s character.

“‘Coop,’ as he was called by most of his colleagues and friends, was generous in sharing his fossils and his knowledge with others,” the statement reads. “He was the role model for two generations of young paleontologists who began their careers at the museum.”