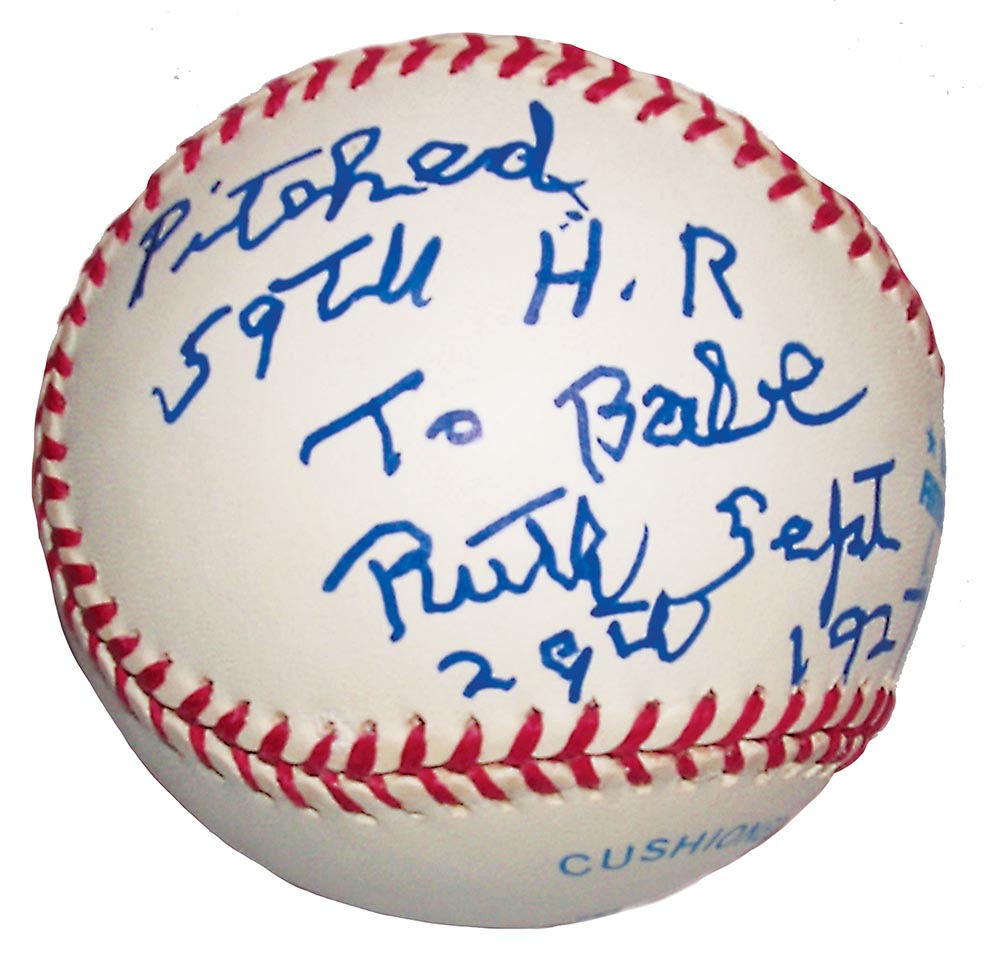

At age 23, Paul Hopkins ’27, P’56 stood on the pitcher’s mound at Yankee Stadium, facing Babe Ruth at the plate. It was Sept. 29, 1927: Hopkins was on the verge of the most memorable moment in his career.

Hopkins was a right-hand relief pitcher for the Washington Senators. Ruth needed only one more home run to tie his own record — 59 homers in a single season.

It was the bottom of the fifth inning, with the bases loaded and two outs. In the bleachers, 7,500 fans buzzed with anticipation.

The larger-than-life Ruth stood with his bat at the ready. The only thing standing between him and his new record was Hopkins, who had just been pulled in from the bullpen by Senators manager Bucky Harris.

“Hopkins was an unexpected choice, and no doubt caused many a spectator to turn to the nearest person with a scorecard for enlightenment,” Bill Bryson recounts in his book One Summer: 1927. “Hopkins … had never pitched in the major leagues before. Now he was about to make his debut in Yankee Stadium against Babe Ruth.”

The pitcher managed to get two strikes on Ruth with well-placed curveballs. Perhaps it would be a mistake in going to that same pitch one more time, but it was the curveball that had gotten the slugger twice already. Hopkins delivered his final curveball, hoping to strike the Sultan of Swat out for good, but Ruth would not be denied.

“At first Babe seemed fooled by it,” Hopkins recalled to Sports Illustrated 70 years later. “Ruth started to swing and then hesitated, hitched on it and brought the bat back. And then he swung, breaking his wrists as he came through it. What a great eye he had! He hit it at the right second — put everything behind it. I can still hear the crack of the bat. I can still see the swing.”

The ball soared over the outfielders and landed halfway up the right field bleacher — an undeniable home run. As the realization struck that Ruth had just set a new record, the cheering of the crowd reached frenzied new heights. (Little did these ecstatic fans know that The Great Bambino would once again break this record the very next day in another game against the Washington Senators, where he delivered his 60th and final home run of the season.)

Following Ruth’s record-setting home run, Hopkins pitched to one more batter, Lou Gehrig, striking him out and ending the inning. Years later, Hopkins would recall bursting into tears as he returned to the bench, overcome with emotion over what had just happened.

In the years that followed, Hopkins pitched only 10 more games in the major leagues before retiring from baseball in 1930 and returning to his home state of Connecticut. He became a successful banker and raised a family of future baseball players, including son Peter ’56 who was a catcher for Colgate’s 1955 College World Series team.

Living to the age of 99, Hopkins shared the story of his fateful pitch against Ruth until the very end. As a bookend to Hopkins’ baseball career, he found himself connected with yet another baseball record: In the days leading up to his death, he had become the oldest major leaguer alive. While Hopkins’ pitching career may have been short, the impact he had on baseball history is undeniable, and his name will be remembered alongside Babe Ruth’s forever.