I had started reading voraciously and writing poems and stories in high school, my limited pocket money spent almost entirely at a used bookstore. I had an inkling that I wanted to be a writer, and at Colgate, I had a professor who was one of the best writers I’ve ever read.

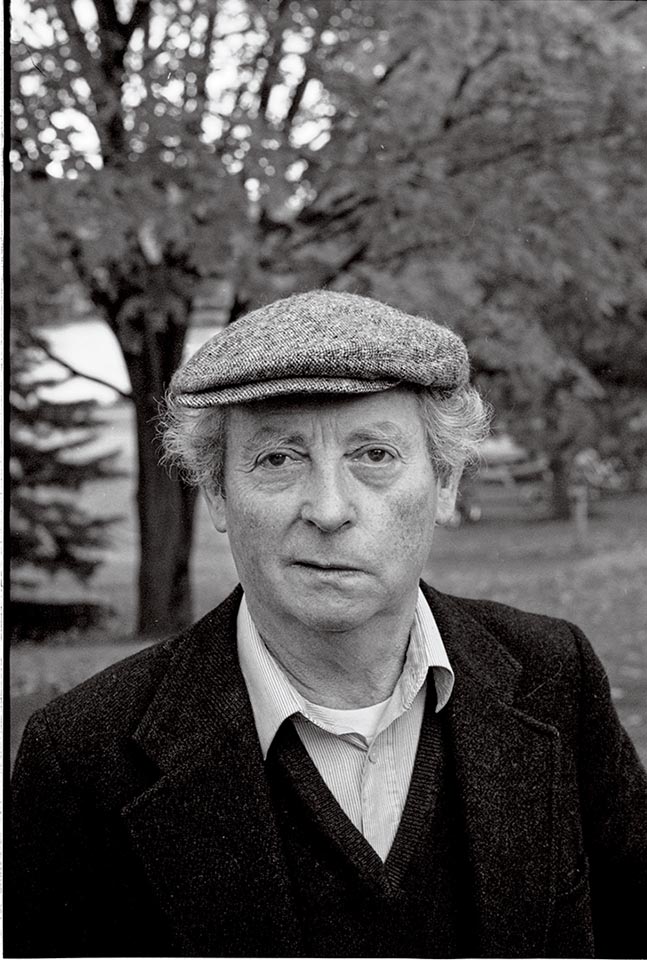

That professor happened to be John McGahern, who is considered the greatest Irish novelist and short story writer since James Joyce. He’s known for his novels, including The Barracks, The Dark, Amongst Women, and his Collected Stories. Some say he was among the finest prose writers of the 20th century. John Updike once wrote: “McGahern brings us that tonic gift of the best fiction, the sense of truth — the sense of transparency that permits us to see imaginary lives more clearly than we see our own.”

For a few years during the late 1970s, I studied creative writing and Irish literature and took an independent study course with McGahern. I would meet him in the hallways or in his office hours, where I gained a sense of how he thought and met his own rigorous standards. I learned as much from those conversations about writing and literature as anything I learned in class.

Because I would write for weekly classes, I always kept my own writing short and sharp — core scenes that were unique and interesting and could be developed into something larger. He said that he himself worked this way. Every now and then he would purposefully write the sharpest two pages he could — what he called a “tuning fork” to make sure that all the writing was consistently at a high level.

McGahern was known for his truth telling and storytelling, his beautiful sentences that floated rhythmically on the page and into the reader’s own consciousness, and his ability to make the language rise to stunning moments of understanding.

He would privately read our work and put check marks next to things he liked. Once I used song lyrics in a story as background, but he suggested that the lyrics too explicitly reflected my purpose. It would be better to write 100 pages that captured that focus and feeling. This was the approach he used to scaffold his own new book, The Pornographer, which he said had one simple theme: “how the young go to the city to live and the old stay in the country to die.”

The amount of time I had with him — during class, independent study, and office hours — has influenced me for more than 40 years. McGahern showed me how fiction writers read closely and gather a store of language, aesthetic convictions, and approaches to storytelling that they draw from writers of the past to add powerful dimensions to their work. If his novels and short stories were just autobiography, they would be far less consequential. But he carefully built his luminous, painstaking prose by borrowing from antiquity to the late 20th century, while hiding those influences in his scenes and sentences.

For McGahern — who had lost his mother at age 10 and was then raised in a police barracks by a brutal but colorful father — writing was a way to relive and relieve the past. He once told me that as he grew older, what he learned most as a writer was “to get to the pain faster.” His own aesthetic view was close to that of the painter John Butler Yeats. The painter once wrote that all art is dreamland, built “all out of our spiritual pain — for if the bricks be not mortised by actual suffering, they will not hold together.”

McGahern was not a rule follower himself. (I once asked him how he could teach Willa Cather’s My Antonia in a course on “The Contemporary Novel.” To which he responded: “There’s nothing more contemporary than good writing.”)

But from McGahern I learned scores of rules that helped codify what he was teaching, that I’ve since made my own, using them in different ways in life and my career:

- Write through suggestion, not statement.

- Allow the rhythm of life to motivate the language, giving movement and order to life’s stasis and randomness.

- Learn from your material. It develops organically from hidden or unresolved conflict, various rites of passage, and other factors that are present from the beginning.

- Keep at it. Your biggest weaknesses can become your greatest strength.

McGahern taught at Colgate eight times, sometimes for whole academic years, spanning each decade from 1969 through 2001. His first stint provided him refuge when he was sacked from his Catholic school teaching job for a combination of marrying outside the church and writing a second novel that, in part, exposed sexual abuse in Ireland and challenged the church’s power. That second book was banned in Ireland.

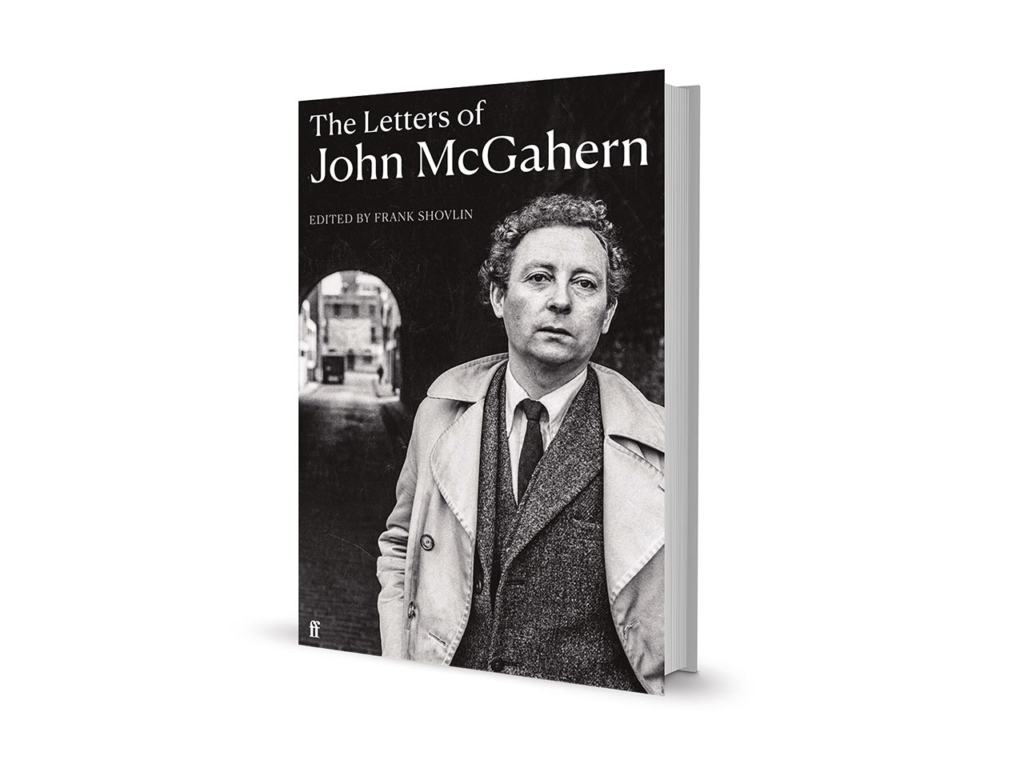

Anyone wondering how he transformed his life — not just the hardscrabble youth but also the tranquil later years — into fiction can learn more from the Letters of John McGahern (Faber, February 2022).

The book includes many letters to Colgate faculty colleagues. It brought me back to other teachers I knew. For example, George Hudson taught me 19th-century British, Southern, and Japanese literature; he led my Japan Study Group to Kyoto and gave us a tour of Russian art museums in Moscow and St. Petersburg during the height of the Cold War. (Sometimes I even helped him fix the roof of his farmhouse in Hubbardsville.) McGahern also frequently references Joe Slater, my adviser. In addition, McGahern and his wife, Madeline, were especially close with English department faculty members Wil Albrecht and Neill Joy and also friendly with historian Doc Reading ’33.

Excerpt, The Letters of John McGahern (Faber, February 2022)

Next Thursday I get my Chevalier’s medal from the French. I get to wear a ribbon like thousands of old fellows.13 Trinity College give [sic] me a doctorate in July and it is now settled that I go back to Colgate for the Fall term. Tell Susan that the delights of Fred Busch’s prose awaits me.

I enclose this piece which was commissioned for a special issue of a magazine for young people, ‘In Dublin’. ‘The Telegraph’ will publish it in London when the paperback of Amongst Women appears in May. I think ‘Liberation’ will publish it in France. I’m sending it in case Miriam might think of some place that it could interest in the States; but it may well be too local.13

With all good wishes

John

Russell and Volkening Papers, 14 February 1991

The things I learned from my professors affected my career decisions. I studied fiction writing with McGahern, and those skills landed me my first job, as assistant to the book review editor of Books & Arts, a national review publication.

Hudson inspired my long-term romance with Japan and my ability to write about other cultures. I’ve written a book-length series of articles on Japanese education for Education Week, and I am just publishing a poetry book about Japan in a Japanese style that is mortised with some of my own painful experience there.

The lessons I learned studying American literature with Slater and from numerous history professors not only helped me to be able to write a book-length poem about the genocide of the New England Algonquians but also to analyze any piece of writing, take stock of new movements and trends, and advance new ideas in education.

My experiences with McGahern, Hudson, and others remind me that students who study literature, history, philosophy, and other disciplines at Colgate gain as much from their relationships with the college’s humanities faculty as our peers in the social and hard sciences gain from close interactions with faculty research mentors. Those who study the humanities at Colgate get a close-up view of how their professors think, internalize lessons from their engagement with great ideas and the world, and apply what they know to their teaching, scholarship, and creative works.

This essay isn’t about me or John McGahern. It is about Colgate and how it changes you. To me, the faculty at Colgate are the institution’s strength and vitality, its heart and humanity.

Sheppard Ranbom ’79 is president of CommunicationWorks, LLC in Washington, D.C., and author of two books of poetry, King Philip’s War and I Didn’t Know Kyoto. If you have stories about McGahern and his teaching, email Ranbom (sranbom@communicationworks.com) so that he may share them with McGahern’s biographer.

Do you have memories of how a Colgate professor positively influenced you? Write to magazine@colgate.edu.