Nestled within Little Hall’s Clifford Gallery, a small white house with two windows, two doors, and an array of tiny portraits was installed in the fall. The structure itself, a one-room building with white painted wood, may appear simple at the outset, but the complexity of emotions that can be felt while standing within those four walls is far from it.

This installation, titled The Little House, opened with a lecture and reception in September. It was the result of a collaboration between lecturer in art and art history Samuel Guy and multidisciplinary artist Marissa Graziano. While Guy and Graziano have been creating art side by side since graduate school, The Little House marks the first time that the two have combined their artistic specialties to create an intersectional installation.

The origins of The Little House go back to March 2020 at a lakeside cottage in Afton, N.Y.

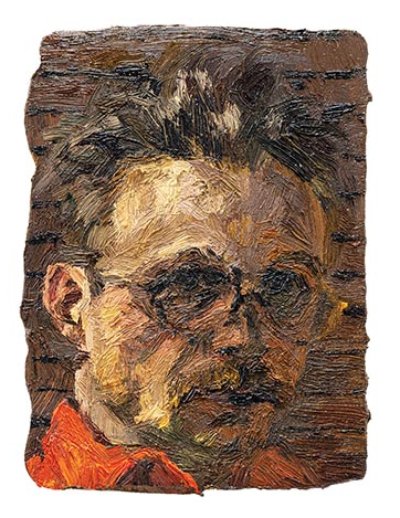

Guy specializes in painting, and Graziano focuses on works across painting, drawing, and visualization.

Through Graziano’s blocking of the house from floor to nonexistent ceiling and Guy’s striking portraits within, the exhibit came to life as a space bordering between a gallery and a home. “The Little House is an alienated space,” explains Guy. “Structurally, it’s a one-to-one replica of a living space, but it has all the character removed to preserve the sense that it is a gallery. In this way, it lives somewhere in between.”

The origins of The Little House go back to March 2020 at a lakeside cottage in Afton, N.Y. When Graziano and Guy took up residence in the little cabin, they had no idea that the COVID-19 pandemic would make it their unexpected home for the next six months. In this state of limbo, Graziano experienced a shift in her way of thinking and viewing the world — one that would ultimately serve as the inspiration for The Little House.

“During those six months, I had to learn how to renavigate the world,” explains Graziano. “I couldn’t feel quite comfortable at the cottage, and I began to think about the lake in relation to traditional horror tropes, such as surveillance.”

One night, Guy and Graziano were taking a walk and realized that most of their neighbors did not close their curtains and, thus, the inner workings of their homes were visible to all.

“It was a fascinating glimpse into domestic life, and I wanted to create something that could emulate the sense of discomfort and fascination that one feels looking in on others and being looked in upon.”

One way that Guy and Graziano achieved this dynamic of being both the viewer and the viewed is through the installation’s two handmade windows. Despite being barely large enough to peer through, these windows were a source of much discussion and consideration between the

two artists.

In her previous exhibits, Graziano traditionally employed peepholes as a way for visitors to experience the installation, almost as spectators. On the other hand, Guy preferred not to have the portraits within the installation viewed in such a voyeuristic manner. As a compromise, they chose to create small windows and place them parallel to important features of the room, such as the main entryway. By using windows as a visual entry point for the installation, Guy and Graziano created a restricted viewing experience similar to that of peepholes but without the negative connotations that accompany the term.

Destiny Sambrano ’21 says she was taken aback by the power of the windows to make her aware that she was both observing the gallery around her and also being observed. “Being inside of the room, I felt as if I was part of the art. Perhaps what I appreciated most were the moments of connection I felt as I peered out the windows and made eye contact with those looking in. Simultaneously, both I and they were the exhibit.”