April Bailey ’14 shows that people are always talking about men, even when they think they’re not.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon’s dusty surface and delivered his famous “one giant leap for mankind” line, it was memorable, if not exactly equitable. An astronaut today might replace “mankind” with “humanity,” or another gender-neutral word. But according to April Bailey ’14, a postdoctoral researcher in psychology at New York University, the astronaut’s audience would still hear those words and think of men.

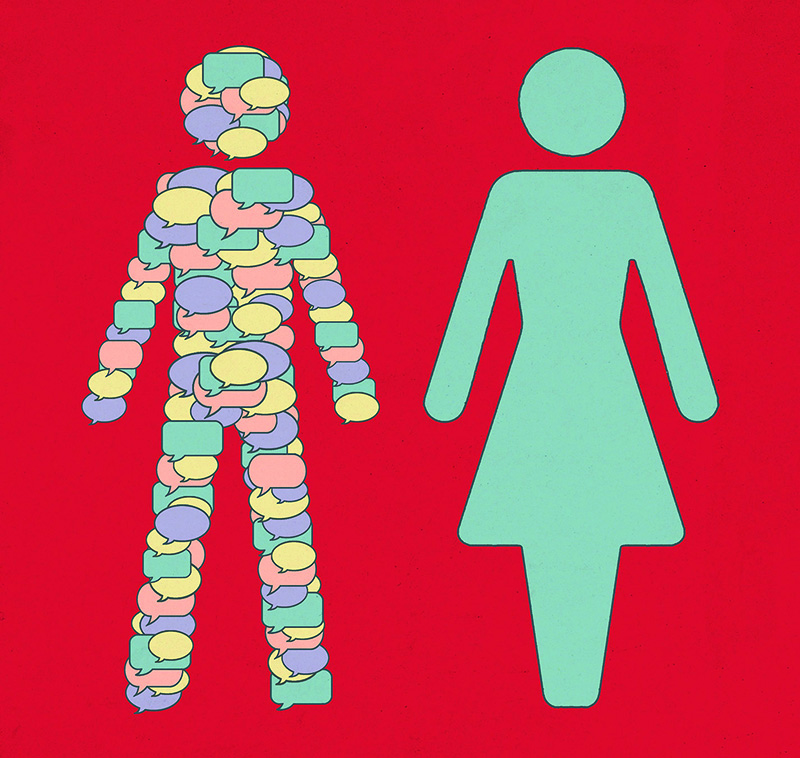

They wouldn’t be able to help it. Bailey’s research shows that for English speakers, words like “person” and “people” are not truly gender-neutral. We associate them more closely with men than with women. And this bias is baked into not just our minds and our language, but also the technologies we use.

Bailey and her co-authors described their findings in a paper published this spring in Science Advances. For their study, they took advantage of a technique known as “word embeddings.”

“This is a really old idea from linguistics, that there’s something important about the meaning of a word that’s captured just by its context,” Bailey says. If you come across an unfamiliar word in a sentence, neighboring words can give you a hint about its meaning: Does it have to do with politics? Pop music? Is it a breakfast food?

The researchers turned to a huge data set called the Common Crawl. It’s a cross-section of the internet, containing more than 630 billion words (mostly English) from almost 3 billion webpages. For any word within this data set, its embedding is a very long string of numbers representing how often the word occurs near other words in the data set. Researchers can then calculate how similar these strings of numbers are to each other.

Whatever the factors are behind our language’s inherent gender bias, Bailey says, it has ‘troubling implications.’

Bailey and her co-authors started with a list of gender-neutral words, including “people,” “person,” “humanity,” “human,” and “someone.” They compared the embeddings for those gender-neutral words to embeddings for a list of male words: “man,” “men,” “he,” and so on. They also looked at embeddings for a third list that included words such as “woman,” “female,” and “she.”

When we talk about “people,” the researchers wanted to know, whom do we really mean?

They found that the embeddings for the gender-neutral words were more similar to embeddings for the male words than the female words. “Our concept of a person, although it’s ostensibly gender-neutral and gender-inclusive, has more overlap with the concept of a man than a woman,” Bailey says.

Further experiments, which looked at lists of adjectives and verbs that were stereotypical to women or men, confirmed the finding. “We think of generic people as men, and men as generic people,” Bailey says. “And we think of women specifically

as women.”

These hidden biases don’t shock Bailey, based on the other research she’s done. “What is surprising about it,” she says, “is that men and women are each, of course, about half of the population.” There’s no reason that we should assume a person

is male.

As Bailey begins a new role as an assistant professor of psychology at the University of New Hampshire, she’s “interested in trying to understand more about where this bias comes from,” she says. For one thing, she wants to explore whether the same biases exist in some non-English languages.

Whatever the factors are behind our language’s inherent gender bias, Bailey says, it has “troubling implications.” When engineers or policy makers are making decisions that will affect all people, are they unknowingly thinking more about the consequences for men?

Furthermore, Bailey says, word embedding isn’t only a tool for psychology researchers. It’s a part of technologies that we use every day. For example, automatic translation uses language embedding to predict meanings. So does predictive text — when your phone guesses the next word in the message you’re sending a friend, for example. And gender bias, as Bailey has shown, is already built into the word embedding data that those programs

draw on.

In her future research, she also hopes to learn about the personal effects of our subtly gendered language.

“What does it feel like to be a woman and to be exposed to this kind of bias — to have other people around you talking about a person or people, and then realize that they don’t mean you as much?” Bailey says. “Women are, in fact, people too.”