Crossing the street to a 19th-century hotel in Denver, Colo., Brian Allen ’74 carried a box of letterpress-printed menus. He’d burned the midnight oil printing 100 menus in two colors (using obsolete 19th-century technology), so Secretary of State Madeline Albright and other guests would know they’d be eating Colorado lamb chops and baby red-skinned potatoes for supper. As he approached the building to deliver the box, he saw two sharpshooters pointing down at him from the hotel’s rooftop. “Not wanting to tempt fate, I called my contact from a pay phone and they came out and got it,” Allen says.

A geography major at Colgate, Allen’s career in graphic design and letterpress printing is filled with such eventful stories as this one from 1997. He was often the man behind the scenes as the companies he worked for made strides, like creating new digital printing technologies and the fonts to be used with them.

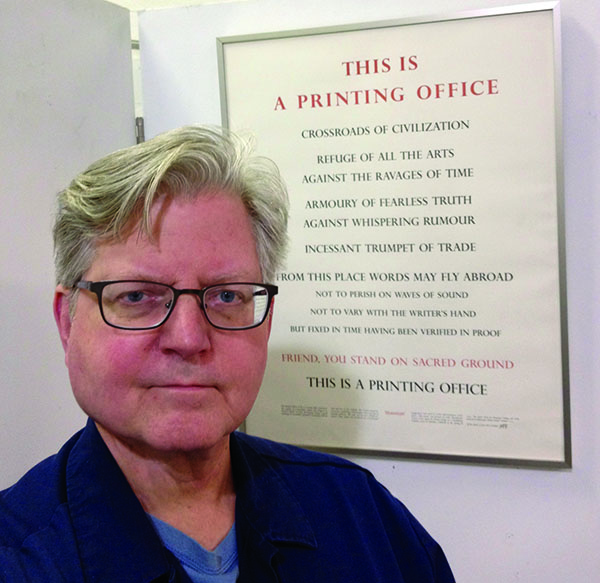

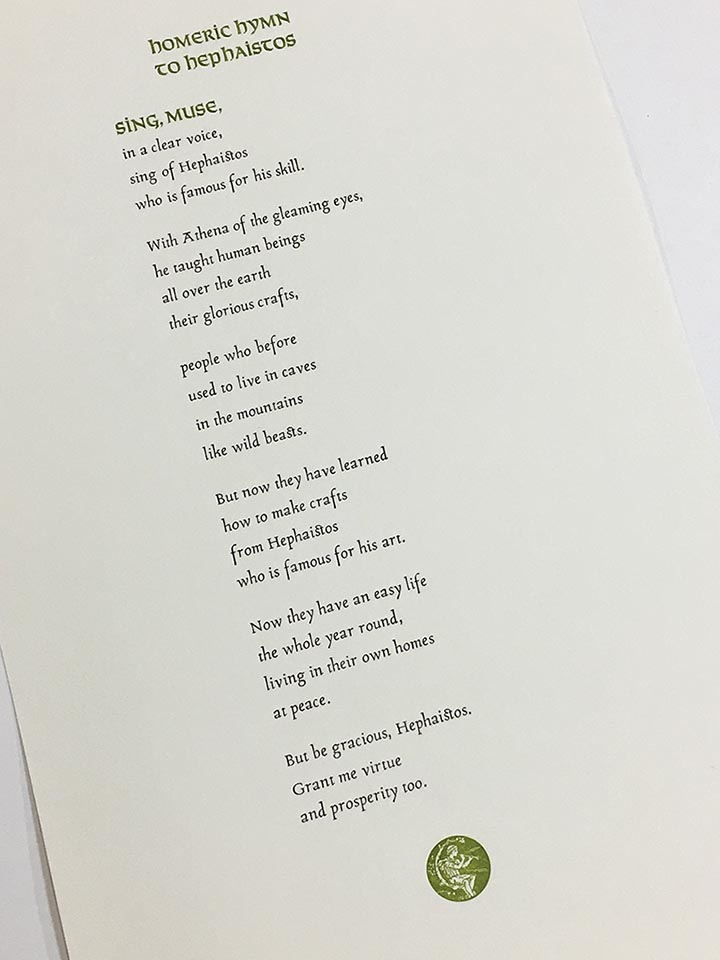

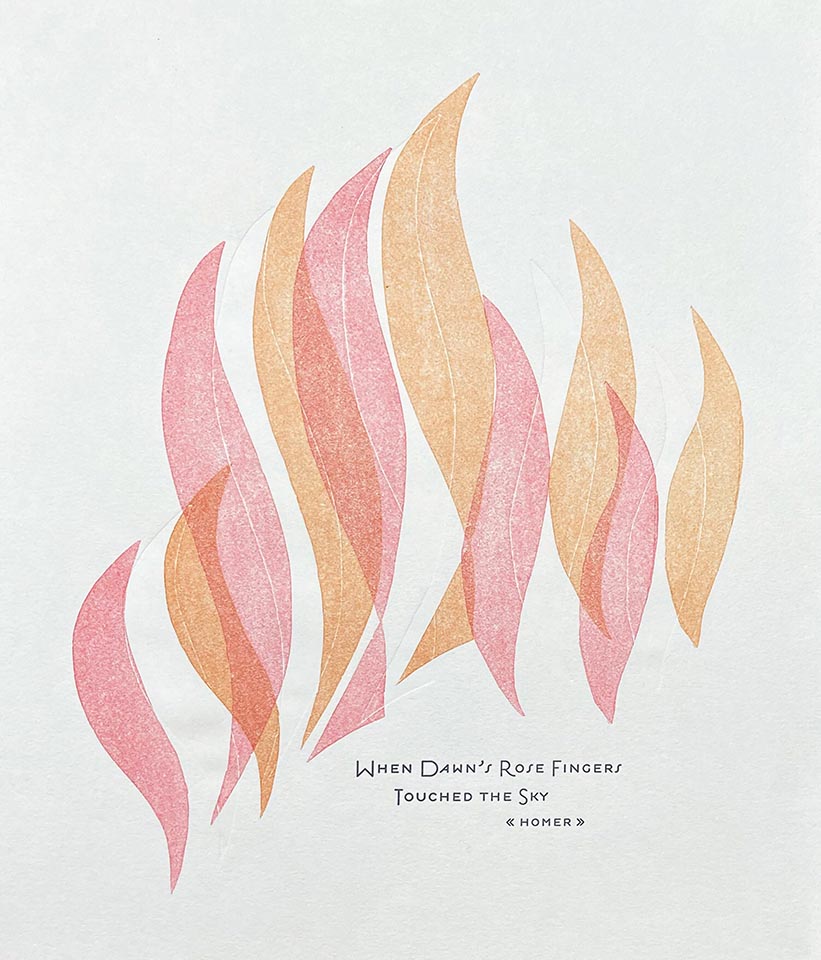

Now in retirement, he continues to create works of art using his letterpress. “My work joins together the legacy of the hand craft of calligraphy and letterpress printing with 21st-century digital technology, and my own aesthetic sensibility, to give form to thought,” he explains on his website.

Learn more about Allen’s journey through the world of printmaking.

From Northwest Georgia to Central

New York

Though Allen’s family is from Vermont, he grew up in the Peach State after his father was transferred by GE. The family often traveled back and forth on summer vacations to visit extended family, giving him the opportunity to see cultural differences between the North and South. “I had a rather disjointed upbringing, the Yankee by night and the Southerner by day,” says Allen, who ended up majoring in geography thanks to those 3-day road trips showing him different parts of the country. “I saw how other people lived.”

Design By Way of Geography

After Colgate, Allen moved to Boston and got a job at a map making company. “That started me in the world of graphic arts,” he says. He learned the basics, like how to set type on the phototypesetting machine, and he became interested in letterforms and typography. While earning his living as a typesetter, he took calligraphy classes on the side.

“I was making the transition into design and typography via the cartographic world,” Allen says. “I see graphic design as a geographic field; for clear communication, text and image are in a dynamic positional balance on page or screen. That’s what geography seeks to understand: how and why things are where they are, or should be.” In 1982, working for Autologic in southern California, he was on the other side of the typesetting machine, making the type for new digital technology. “This was the new frontier of communication,” he notes.

That Time His Handwriting Became a Font

Allen spent two decades making fonts for digital machines at several companies, including IBM. “Through all of this, the technology was changing rapidly,” he says. “We were very adaptable.” While working at the firm Monotype, his handwriting was turned into the fonts Segoe Print and Segoe Script for Microsoft. “In addition, Monotype had been a British company and was part of the empire, so they made metal type for all the colonial communications. There are fonts for South Asian scripts like Hindi and Devanagari. These are reference materials for digital fonts covering world languages to support our connected world,” he says.

University Printing

In 2006, Allen moved to Raleigh-Durham, N.C., to be closer to family and start his own letterpress business. Clients included the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University.

One of his favorite creations is a broadside bearing the words of designer Rudolf Koch: “We are type designers, punch cutters, wood cutters, type founders, compositors, printers, and bookbinders from conviction and with passion, not because we are insufficiently talented for other higher things, but because to us the highest things stand in closest kinship to our own crafts.”