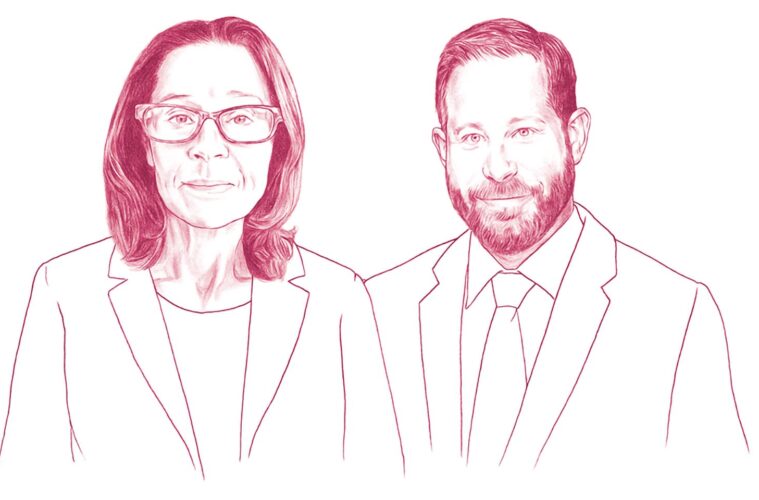

Two alumni are changing the lives of incarcerated individuals

Sally Moran ’84 Davidson is an economics and finance professor, teaching concepts like scarcity and risk tolerance, but her classroom isn’t the typical college lecture hall. At the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Concord (MCI-Concord), her students have no access to Wi-Fi, so even a Zoom class is out of the question. Instead, in a bare room with just a few desks, she asks for volunteers to come up to the whiteboard to solve complex problems. Hands shoot up, eager to hold the Expo marker and work through questions in front of the class. “[When] you’re in a smaller space with fewer students, there’s a lot more conversation that happens,” Davidson says. “They ask questions and they support each other.”

Davidson first became involved with prison education while developing a new course at Columbia University called The American Economy, which focused on inequalities around income, wealth, gender, and health, among other topics. While researching areas of focus for the course, she came across the Bard Prison Initiative. Soon she started teaching economics to students in the New York State Prison System, in addition to her classes at Columbia. Later she became affiliated with Columbia’s Justice-In-Education Initiative before relocating to Boston and joining the Emerson Prison Initiative, through which she now teaches.

The experience of teaching the men at MCI-Concord is understandably different from teaching 20-year-olds on campus. “They’re older, first off; they have very different life experiences than an undergraduate student,” Davidson explains. “They just do all the work, everything. You could be reading a paper and they’re going to ask questions about the footnotes because they read things that deeply.” The men apply themselves, and work hard to master the material taught in class, because they want a different life for themselves when they reenter their communities, she adds. The program’s first cohort of students, which started coursework in 2017, will graduate with their BAs in September. Their degrees won’t be any different from students who studied on Emerson College’s Boston campus.

Davidson’s interest in economics dates back to her Colgate days. “I started off taking math [courses] and knew nothing about economics,” she remembers. “[I’d] never even heard the term economics as a kid and just decided to take a class. And I really liked it.” She thrived under the mentorship of assistant professors of economics Mary Jo Kealy and Mark Rockel, with whom she collaborated on research projects. And following the Colgate tradition, they often invited Davidson over for dinner and good conversation.

After Colgate, she worked as a research assistant and assistant economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, followed by a stint at JP Morgan Securities providing support for government bond and foreign exchange trading. “At that point, I realized I should just go back to what I really loved, which was economics,” says Davidson, who earned her PhD from Columbia in 1999.

Davidson taught economics and finance at Columbia for almost two decades — even helping to create a financial economics major — but teaching her students today is in some ways more rewarding. She says the prison is a challenging and exciting environment to teach within, and the mutual respect she’s able to foster with her students allows them and her to thrive.

“One of the things that has always been true for me is, I like my students,” she says.

“They are incredibly hard working and very smart. “They want a different life, and they work really hard to achieve that. When they’re released, they want to be part of their communities. They really embrace education as a way to have a good life.”

Representing the Forgotten

“It’s been a long struggle,” Joyce Watkins said the morning she was pronounced innocent.

In the late 1980s, Watkins, along with longtime boyfriend Charles Dunn, was convicted in the brutal rape and murder of her great-niece. Watkins received a life sentence and ultimately served 27 years

in prison before her exoneration on Jan. 12, 2022. Dunn died several years ago, but until her charges were dismissed by the Davidson County, Tenn., criminal court judge, Watkins maintained their innocence and fought for her release.

As senior legal counsel with the Tennessee Innocence Project, Jason Gichner ’99 was at the helm of Watkins’ case and ultimately helped her become the first African American woman to be exonerated in Tennessee.

“I feel very lucky and fortunate that I was able to represent them, but it’s also heartbreaking,” Gichner says. “Joyce and I are very close. She’s like my adoptive grandmother at this point. That case meant a lot because of how tragic it was, what happened in the case, what happened to these two people, and because I just care about Joyce.”

Gichner first became involved in Watkins’ case when he joined the Innocence Project in 2021 after years of public defender work. Because she was convicted based on medical evidence rather than witness testimony, Watkins had a real chance of exoneration. Thanks to modern technology, defense lawyers were able to discern that the original 1987 medical examiner made a mistake regarding the timing of the victim’s injury. With the help of a Vanderbilt University pediatric neurologist and the current Tennessee chief medical examiner, it was clear that Dunn and Watkins were not with the child at the time of the crime.

Nashville has had an uptick in exonerations in the last year, Gichner says, and several factors contribute to that statistic. First, the city has a robust conviction review unit, which aids litigators in examining old cases, looking for errors. Also, now that the Tennessee Innocence Project, which started as a nonprofit in 2019, has been around for a few years, a backlog of cases is finally being tended to. Each file the Innocence Project takes on is carefully vetted, and the team often receives recommendations from other lawyers who want rulings on their previous cases reexamined. “One thing that limits the cases we take is that we only represent people who are claiming to be actually innocent,” Gichner says. “We are only taking cases for folks who say, ‘I was convicted of a murder I didn’t do.’ If it’s a self-defense case, that’s not a case we would take. If it’s ‘the police illegally searched my car and found something they shouldn’t have found,’ that’s not a case we would take.”

Gichner’s work has always centered on public interest law, with a decade spent at the Nashville public defender’s office before another 10 years doing civil litigation and criminal defense work. Now, he’s one of only three full-time attorneys at the Tennessee Innocence Project: “There’s a lot of people in prison who are wrongfully convicted who need help, but there’s not a lot of lawyers who do this kind of work.”

Even so, if Watkins’ release is any indication, there are more exonerations to come for the people of Tennessee.