She’s representing the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. He’s solved a Paleozoic mystery in a South China quarry. She opens eyes by teaching a curriculum centered on the worldviews of Indigenous people in Maine. These and other alumni who work in museums are challenging expectations.

Before the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA) took shape as a 65,000-square-foot architectural marvel on the city’s waterfront, it resided in an old police station on Boylston Street.

“It was built in the late 1800s to keep people out, and it successfully did that the entire time the ICA was in said police station,” museum director Jill Medvedow ’76 quipped on the podcast Art Scoping last fall. “It didn’t have much of an audience, it didn’t have any money in the bank, it didn’t have much of a staff, and … its printer didn’t print v’s and w’s — which, with my last name, was very difficult. So it needed change.”

Medvedow launched that initiative, transforming not only the museum — which was the first built in Boston in a century — but also the city. Her leadership in the building project, which was completed in 2006, has been covered in numerous Boston Globe articles and is even the subject of an MIT Sloan School of Management case study.

This past spring, Medvedow entered the global spotlight when the much ballyhooed Venice Biennale began: She and the ICA’s chief curator served as co-commissioners of the U.S. pavilion at the world’s biggest art exhibition. They were awarded the commission based on their proposal to the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, which holds an open call.

The proposal’s acceptance was not only an important moment for the ICA, but it was also historically significant because it features artist Simone Leigh, the first Black woman to represent the United States at the Biennale. Now installed in Venice, Leigh’s Sovereignty is a series of figurative sculptures that represent the labor of Black women in colonial history. Part of the co-commissioners’ “massive responsibility” was to “ensure that the artist’s ambitious, glorious vision can be realized in all of its beauty,” Medvedow says.

The museum director has championed women artists since her days as an art and art history major at Colgate in the University’s nascent coed era. “Those were incredibly important relationships of early Colgate women in the arts, sticking together,” Medvedow remembers.

After graduation, she ran artist spaces in New York City and Seattle before heading to Boston. In 1991, she became the first full-time contemporary curator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “This city has always had extraordinary collections, but it did not have a culture of contemporary art,” Medvedow said in the Boston Globe. By “building interest and excitement for contemporary art in Boston, which had been a city much more connected to its past than contemporary art and culture,” she says, Medvedow has forged her path.

Deciding to leave the Gardner Museum in 1998, Medvedow founded a public art initiative called Vita Brevis. The Globe referred to the temporary installations — set up at Boston landmarks and focusing on issues such as urban violence and the legacy of slavery — as her Trojan horse. “I thought that maybe the way to get contemporary art through to Bostonians was through the things they already loved,” she told the paper.

Soon after, Medvedow was chosen as the ICA’s director. “The minute you met Jill, you immediately noticed that she is centered … she is not the least bit pretentious,” ICA board member and head of the search committee William Rawn said in the MIT case study. “She isn’t out to prove anything to anybody. She has a strong intellectual base for her opinions on art. This part of her persona was reflected in her vision for the ICA, which was something that really struck us.”

With lofty aspirations as she took on this role, Medvedow started making plans to take the ICA to a higher level. She envisioned a new building, with a permanent collection (it had previously only featured changing exhibitions) and crowd-drawing appeal, as a “platform for the work that needed to happen.”

Less than a year into her tenure, Medvedow learned of a competition for a waterfront parcel of land earmarked for a cultural site. Two previous directors were unable to convince the board to change the ICA’s location, but Medvedow succeeded, won the competition against several other major cultural proposals, and announced the organization’s first major capital campaign ($62 million).

The details of this effort are a long and winding tale, but it all boils down to Medvedow’s gumption. She credits her father — longtime New Haven, Conn., politician Leon Medvedow, from whom she “learned how to move an agenda” — and her Colgate education. “It is this background of political organizing [and] my degree in art history that has formed my version of cultural leadership and an understanding of how to navigate the really conservative oppositional waters in Boston when we were building the new ICA,” she said on Art Scoping.

As Medvedow was working to advance Bostonians’ attitudes about contemporary art, she was simultaneously helping to improve the cityscape. The ICA’s new location on Fan Pier is in the Seaport District, which at the time was just “above-ground, rubbly parking lots,” she says. “No one came to this neighborhood. There was a huge amount of skepticism: Would anyone ever come to the ICA?”

In its first year, the ICA welcomed more than 280,000 visitors and has held steady. The Seaport District is now rows of steel and glass structures, tech companies, hotels, and pricey condos. “It’s a lively neighborhood now,” she says. “That has been part of both the city’s change and the ICA’s change. It is considered to be part of the fabric of the city through our partnerships and programs.”

The permanent collection comprises 350 artworks, which include more pieces by women than men and almost 40% by artists of color. “We have an intentional focus on addressing the gaps in art history and history in terms of representation according to race and gender,” she says.

Featuring Leigh’s work at the Biennale is demonstrative of this commitment, as is the ICA’s plan to bring Sovereignty back to the museum when the Venice event ends. “I have this dream, and great optimism, that we can have every 9th-grader in this city come to the ICA to see this show, and then every class will go home with a classroom kit…. Because it’s that important,” Medvedow says.

Art education is another one of Medvedow’s main objectives. The ICA forged a partnership with Spelman College to have a yearlong seminar at the HBCU on the arts and ideas of Leigh. In Venice, the ICA organized a teacher training to prepare educators to bring their students to the Biennale. And back in Boston, the ICA opened Seaport Studio across from the museum as a space for teen programs and exhibits. Pre-pandemic, there were approximately 7,000 teenagers a year participating. “That reflects our long-standing commitment to the next generation of artists, thinkers, leaders, and electorate,” Medvedow says. “As we know, young people who participate more in the arts are more civically engaged as they grow older.”

Medvedow herself has been immersed in the arts since childhood, when she spent time with her mother’s best friend who was a professional artist, learned to paint, and frequented the Yale University Art Gallery with her mom. Medvedow’s parents were deeply engaged in the community and passed that virtue down to her.

“There is a core value of civic life that runs through her,” ICA board member Charla Jones told the Globe.

During the height of the pandemic, the ICA converted its third building — Watershed, an industrial space for art and community events — into a distribution site for fresh food and art kits for East Boston families. More than 50,000 people were served.

Broadening equity and access can be achieved through many different avenues, as Medvedow has proven. As she facilitates change, Medvedow considers the role of the arts: “One of the things I love best about contemporary art is that when we really, truly encounter it and put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, it elevates the dignity of each of us,” she said on Art Scoping. “We see people anew, we see ideas anew, we can imagine things that we hadn’t thought of before, and I think that the arts are part of this flourishing of truth and openness and expansion, and the circle is just so much better for being bigger.”

‘The Public Was Ready for This Kind of Show’

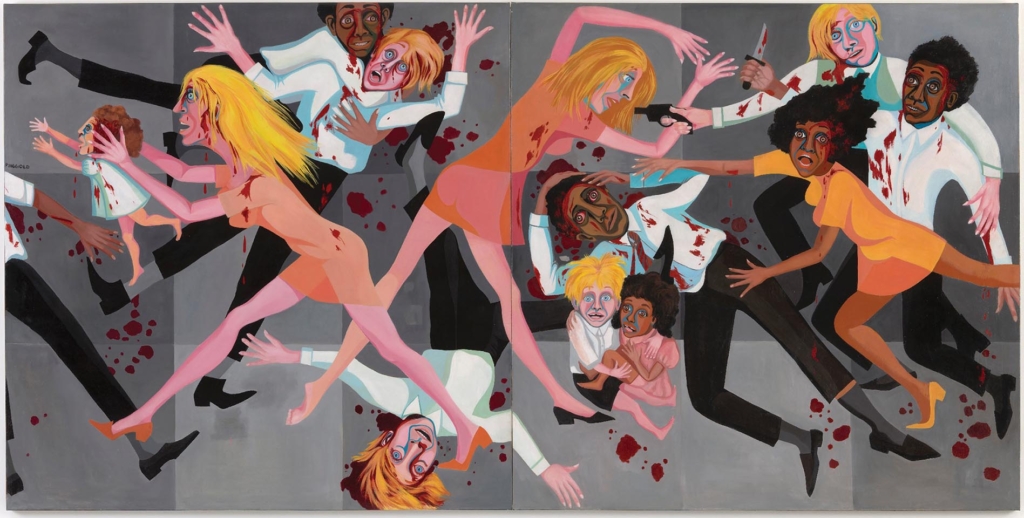

When MoMA unveiled the rehang of its permanent collection in 2019, it placed a mural-size painting by African American artist/activist Faith Ringgold titled American People Series #20: Die alongside Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The pairing set off a flurry of discussion about representation in the art world.

This summer, MoMA loaned American People Series #20: Die to the New Museum in Manhattan for its exhibition titled Faith Ringgold: American People, co-curated by Gary Carrion-Murayari ’02. The media has since turned its attention to this six-decade retrospective, calling it timely for the 91-year-old artist whom the New Yorker, for one, asserts “is sorely overdue for canonical status.”

Carrion-Murayari weighs in: “For many people, she’s a real icon of American culture, but she, for whatever reason, hasn’t had recognition by major institutions in New York.”

These are the types of artists whom he highlights in his position as the Kraus Family curator at the New Museum, which is devoted to contemporary art.

From the Whitney to the New Museum

“I’d been at the Whitney for several years, and I was working primarily with contemporary art by the time I left. The New Museum was a natural place to go … working in a museum that’s exclusively devoted to contemporary art was a logical step. [Also,] the Whitney is exclusively devoted to American art, and contemporary art today is an international field, so it makes sense to have a global vision.”

New Age

“The last several years I’ve been working more with senior artists. In recent years, we’ve done shows with Hans Haacke and Peter Saul — both in their 80s — who are incredibly influential to young artists. I’ve worked with many younger artists, so I know whom they look up to, the ones they think are heroes, which are not necessarily the ones that [larger institutions] are showing. It’s also the case with [these older artists that] you want them to get accolades while they’re still alive. I think that’s a really, really important thing.”

Mind the Gap

“I’ve been working in museums for 20 years now, so I’m very familiar with where the gaps in collections and programs are. I think I do have a sense of responsibility for using the platform I have to address those gaps within our living art history.”

Soul Searching and Critical Thinking

“In the last couple of years, museums have had to do a lot of soul searching and critical thinking about what they do and how they operate across the board. Some of those are issues about representation programmatically, which is important, but it’s also about equity within the institution, how institutions are run, and who has a voice within the institution in what the museum does and how it operates. It’s not just about what we show, but it’s also about who’s deciding what we show. For a lot of us who’ve been in museums for a long time, it’s been long overdue for those kinds of discussions to happen. It’s been refreshing, and I think we’re already seeing the benefits.”

Paving the Way for Canonical Status

“Faith’s show has been incredibly well received. The [monograph, which

Carrion-Murayari co-edited] is probably the bestselling book we’ve ever made. [It was #1 on ARTnews’ ‘Essential Books: 9 Recent Monographs on Women Artists’.] The crowds at the museum are at the level of pre-COVID, which is pretty amazing to see. So we know that we made the right choice … the public was ready for this kind of show.”

Fortune Favors the Brave

In Eric Carle’s beloved children’s book Papa, Please Get the Moon for Me, a girl named Monica asks her dad to carry out an extraordinary feat — which he does, with a ladder and patience.

Carle (perhaps best known for The Very Hungry Caterpillar) himself accomplished a pioneering act, in 2002, with opening a type of institution he’d seen in Japan — a picture book art museum — in the U.S. The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Mass., has since welcomed almost 1 million visitors.

And in 2008, Alix Kennedy ’82 embarked on a new mission when she joined Carle’s vision and became executive director of the museum.

“It felt like too big of a jump,” Kennedy remembers thinking when a board member approached her about the position. An English major at Colgate who earned her MFA in poetry, she’d built her career as a magazine editor, starting out at New England Monthly and then spending almost 20 years at Disney Publishing Worldwide, where she was ultimately vice president and editorial director. After further consideration of the opportunity, she determined: “I was almost 50 and it felt like a big chance to try something new and very different.

“I had never run a nonprofit; I didn’t know a lot about children’s books,” she adds. But she had what The Carle’s board was looking for: someone who had executive experience with strategic planning and a familiarity with a family audience. Kennedy had managed Disney’s four U.S. publications and was a liaison among the publishing headquarters in New York City, corporate headquarters in California, and her team in Massachusetts.

On the personal side, she has two sons to whom she had, of course, read Carle’s books. “I loved reading Brown Bear to my children,” she says. “But Papa, Please Get the Moon for Me was always my favorite book. It has that amazing moment where you fold out the page and the ladder goes all the way to the moon. It really speaks to the experience of being a parent and how much we want for our kids.”

Carle’s books are among many children’s first, and The Carle can be the first art museum experience for youngsters. The two go together like peanut butter and jelly. “Picture books are their introduction to literature, their introduction to art,” Kennedy says. “The work we do helps to encourage generations of children to become readers, to become lovers of art, to make art … lifelong learners in that sense.”

And although many visitors to the museum are parents with children, a lot of adults come on their own. “They’re there because they love illustration and children’s literature,” Kennedy says. Instead of considering itself a children’s museum, “We think of ourselves more as an art museum that’s really welcoming to children.”

Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, the museum highlights picture book artists and writers from around the world. In addition to doing this at the museum in Amherst, the collections travel the world.

In 2017, Kennedy went to Japan — the country Carle loved and where he found inspiration — with Carle when his work was on exhibition in Tokyo. “It was a very special thing for me to be able to do with him,” she recalls. “He had an incredible wit, he was a lot of fun to be with, and he was a big-hearted guy,” she says of the icon who died in May 2021.

As demonstrated by the style of his work and the creation of his museum, “Eric was a guy with big dreams,” Kennedy adds, “and he was bold.” It’s likely that his characters Monica and her papa would approve.

A Renaissance Woman

Rachel Kordonowy ’95 McGarry will tell you she’s not an emotional person. But when she recently stood face to face with the frescoes in Florence’s Brancacci Chapel, she says, “I absolutely teared up.”

Masaccio’s Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden (c. 1424–27) is known as a heart-wrenching painting, depicting a naked Adam and Eve shamefully leaving the Garden of Eden after being banished for their sins. But it was the proximity to the masterpiece more than the scene itself that bubbled McGarry’s feelings to the surface. She’d had the rare opportunity to see the chapel’s frescoes from just a few feet away, thanks to scaffolding that’s in place for restoration but has been opened to visitors.

“They’re made to be seen from a distance and they have a lot of expressive power,” McGarry explains. “So, when you get up close, they have an even stronger result. [And] there are so many details you can see the artists added, almost for their own enjoyment.”

She remembers studying these Italian Renaissance paintings in one of her first art history classes with Professor Mary Ann Calo. “I was more of a math and science kid in high school,” McGarry says, “but I took my first art history class and just absolutely loved it.”

She ended up majoring in art and art history, an experience that extends in many ways to her current role as the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s Elizabeth MacMillan Chair of European art and curator of European paintings and works on paper.

During her trip to Italy this spring, she attended the Venice Biennale (perhaps passing Jill Medvedow ’76 in the crowd). The last time McGarry was at the Biennale, she was a junior participating in the Venice Study Group led by Professor Rebecca Ammerman. From that semester abroad, McGarry says, “I knew I wanted to study Italian painting and drawing.”

The group went to Rome, Naples, and Pompeii, exploring classical art and archaeology. They studied Latin literature and translation, including Ovid and Livy, whose work is on her office shelf today. “I still draw on much of that knowledge,” she says.

Ammerman brought McGarry back to Italy the next summer to work at the National Archaeological Museum of Paestum to assist the professor on a book about terracotta figurines dedicated at the sanctuaries and temples. “We were in the basement cataloging the terracotta colors…. It was a really great experience,” McGarry recalls. “And the mozzarella di bufala is delicious there, and you’re at a beach…. It was an amazing summer.”

As a senior, McGarry defended her thesis on Lucanian tomb paintings at Paestum from the 4th century BC in front of a dozen faculty members. “It was like an oral exam; you really had to know what you were talking about, and you really had to prepare,” she says. “It was a very rigorous academic exercise.”

These experiences added up to McGarry being fully prepared when she entered NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts for her PhD. “I remember feeling very privileged to have come out of Colgate’s art and art history program…. I got a ton of attention from the faculty.”

She wrote her dissertation on Guido Reni and, this spring, went to see his work again in Rome as she prepares her contributions for an exhibition at the Prado on the Italian painter next year. In the meantime, McGarry has been putting together an exhibition she’s co-curating on Sandro Botticelli

(1445–1510) with the Uffizi Gallery that will open in Minneapolis this fall.

Comparing it to her undergraduate thesis, McGarry says the Botticelli exhibition — and often anything with artists from earlier periods — involves a lot of piecing together what little information is available and trying to parse fact versus myth. “You don’t have a slew of archives and documents to build facts on,” she says. “It’s complicated and time consuming, but fascinating.”

Uncovering the How and When

The Great Dying — the end-Permian mass extinction — 251.9 million years ago wiped out 96% of marine species and 70% on land. “It’s the largest mass extinction we know of,” says Douglas Erwin ’80, a senior research biologist and curator of Paleozoic invertebrates at the National Museum of Natural History. The Atlantic calls Erwin “one of the world’s experts on the end-Permian mass extinction.”

The leading theory on why the extinction happened is that it was caused by massive volcanism in Sibera, but Erwin and colleagues recently discovered that there’s more to it than researchers previously thought. They have also been trying to determine how rapidly the extinction happened. He elaborates on his research, their findings, and the remaining mysteries:

“The best record of it is in China,” says Erwin, who began working there in the early 1990s. He and colleagues have been collecting ash beds to “get precise estimates of the age of the eruption of those volcanic events that produced the ash so we could tell how fast this extinction occurred, and thus get a better idea about the causes of that.”

Scientists have believed that the cause of the extinction was a large eruption in Siberia. But Erwin and his colleagues have proven that“there were actually more volcanic events than we had initially thought….We discovered that there was a different kind of eruption in South China that released this huge cloud of mercury and copper and other volatiles that was a contributing cause to the extinction.”

“The evidence we have is an ash bed in South China, within marine rocks. There was a big volcanic eruption, the ash goes all over the globe, it eventually settles out, settles on the water, and then settles down through the water. The sediments eventually become limestone or mud, depending on the environment. One of the places we often go in South China is halfway between Shanghai and Nanjing, just south of the Yangtze River. It’s an old quarry.”

“We’ve found tons of fossils. The volcanic ash beds that we collect are interbedded with a lot of other deposits that are full of fossils.”

“There are still lots of questions. With most research, as soon as you think you’ve answered one question, you realize that just opens up a bunch of other questions. Why did this group go extinct, and not that group? There were a number of things to get through — lots of gastropods and sea urchins, trilobites. You look at what survived and what went extinct, and you can then ask, is it because of different geographic regions, or because of the physiology of different groups of organisms? What were the factors that may have played a role? How do we get the data to test those ideas?”

“Most of my job is research, but there’s certainly an outreach component to what we do.” For example, Erwin co-curated an exhibit on the Cambrian Explosion that traveled around Canada and the U.S. for about 10 years, to smaller museums through the Smithsonian traveling exhibit service.

The Atlantic calls Erwin “one of the world’s experts on the end-Permian mass extinction.”

Erwin is curator of Paleozoic invertebrates at the Smithsonian. So what’s his favorite invertebrate? “Opabinia, which is one of the Burgess Shale animals from the Cambrian. It’s a soft-bodied organism that was found by Charles Walcott, the fourth secretary of the Smithsonian and a paleontologist in British Columbia, which is where the Burgess Shale is found. Opabinia had five eyes on stalks on its head, and it originally had two appendages that were fused into what looks like a tube, so it looks like it has this long proboscis with a claw on the end of it. They’re about 3–5 inches long. They’re what Steve Gould [a former Harvard professor] called a ‘weird wonder,’ because they’re such a bizarre animal.”

“My first paper at Colgate in my freshman seminar in Lathrop Hall was on the end-Permian mass extinction. My senior thesis was on the origin of the animals in gene regulatory networks, so the same two questions that I was working on with Bob Linsley [Whitnall Professor of geology emeritus] at Colgate have gone through my entire career.”

The Elements of a Curator

Emily M. Orr ’06 likes to know how things are made — from a 1916 iridescent Tiffany vase to a 1999 iBook laptop.

Here, we look at the elements of Emily:

At Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in Manhattan, Orr is associate curator and acting head of the product design and decorative arts department. “We are the nation’s design museum,”

Orr says. Housed in Andrew Carnegie’s former mansion at 90th Street and 5th Avenue, the museum houses approximately 215,000 objects, including ancient ceramics, buttons, everyday objects like radios, and decorative items like textiles, prints, and graphic design.

“I specialize in American design from 1850 to 1950, which is the golden age of industrial design. It’s a field in which women have often worked anonymously or not been credited; and that really applies across media — we find it with textiles and graphic design as well. Now, with a lot of new resources available and research, [we’re able to] give credit where it’s due.”

Orr not only researches how items are created; she also helps develop the exhibitions. This entails collaborating with an exhibition design firm to determine the visitor flow and how to trace a narrative. “It involves everything from figuring out the layout to writing the labels to working with our teams [to decide] how things will be framed, how they will be displayed, what is required for security, and how we physically build the show.”

An exhibition Orr co-curated on American graphic designer E. McKnight Kauffer wrapped up this past spring. Titled Underground Modernist, it was the largest-ever retrospective on Kauffer, who produced advertisements, illustrations for literature, and posters in the early 1900s. “He was known as the poster king because he innovated poster design for the London Underground, among other clients,” Orr says.

Exhibitions can involve “crazy lead time,” says Orr, who began working on the Kauffer exhibition and accompanying publication in 2017. Through an Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom-Smithsonian Rutherford Fellowship in Digital Humanities, she spent three months of 2019 in London, in residence at the Victoria & Albert Museum, digging through its archives. She also met with Kauffer’s grandson and visited other collections to evaluate loans for the exhibition to supplement Cooper Hewitt’s holdings.

“I love teaching and mentoring; it’s an important part of the work that I do here,” says Orr, whoguides master’s students through an MA program Cooper Hewitt offers in partnership with Parson’s School of Design.“Whenever possible, we give [students] access to the collection,” she says. “We do object sessions — turn over objects, look at things in three dimensions, examine marks, and think about the weight of something.”

As a Colgate student, she worked at the Picker Art Gallery, cataloging works on paper and learning how to use The Museum System database. Knowing how to use that database is “foundational to being a curator,” Orr says.

After graduation, she was in the NYU master’s program called Visual Culture: Costume Studies, which was connected to the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Leaving that program, I knew that I wanted to be in museums and continue working with objects,” Orr says.

She then became the Marcia Brady Tucker fellow at the Yale University Art Gallery. At the time, Yale was doing a permanent reinstallation of its American decorative arts galleries and period rooms. Orr says: “That experience transformed and expanded my thinking and my learning about design.”

To work on her PhD in the history of design, she moved to London to be at the Royal College of Art and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Her thesis was on the design of department stores at the turn of the 20th century, which she finished in her first years at Cooper Hewitt as the assistant curator of modern and contemporary American design in 2015 (Orr was promoted a few months ago).

Her Colgate art history thesis influenced her PhD thesis, which became a book titled Designing the Department Store: Display and Retail at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019). “Props to Colgate for encouraging me to research and write on what I was interested in — fashion, retail, and exhibition design — because it wasn’t a traditional art historical topic.”

In April 2023, she’ll be curating an exhibition on symbol design in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Symbol Sourcebook by Henry Dreyfuss. A designer known for his work with Bell Labs, Polaroid, and airlines, Dreyfuss “realized that, as his consumers and his products were traveling faster around the world, he could use symbols to instruct and keep people safe,” Orr explains, “and [he identified a] number of ways that symbols could improve our lives and bring us together across language barriers.”

As is her approach with each exhibition, Orr will be looking at the history of the subject and bringing the story into the present.

“The show will talk about the making of the Sourcebook in the 1970s, but also ask visitors to contribute to a Symbol Sourcebook of 2023, prompting them to consider what new symbols we need today and what symbols mean to their daily communication, right up to the latest emojis.”

Welcoming Everyone

“Museums never felt accessible to me as a young person,” says Starr Kelly ’10, MAT’13. Because of that, she now makes sure those doors are open to today’s youth, as the director of education and exhibits at the Children’s Museum and Theatre of Maine in Portland.

Kelly grew up in Portland and is an enrolled citizen of Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, a First Nation community. Family finances were one barrier to museum trips. At the children’s museum, she partners with housing authorities and social service agencies to broaden membership scholarships. Her institution is also part of Museums for All, a nationwide program through which people receiving food assistance can get free or reduced admission.

But it’s not just about getting people in the door, Kelly says — it’s also about making kids and families from all backgrounds feel welcome. “Speaking from my own experience, being an Indigenous person, certain museums have definitely felt off limits as far as their connection to colonialism and hoarding items as a result of colonialism,” she explains. “I’m specifically thinking about collections with actual human remains … it can be really off-putting, but also a really harmful experience to go into a museum and see an ancestor on display or to see burial items on display.”

Kelly began unpacking those issues further while majoring in Native American studies at Colgate, especially through a museum studies class with Professor Jordan Kerber. “Even though we didn’t use words like ‘decolonization’ at the time, the course really dug into the power that museums have over the narratives of Native people, and how institutions, curators, or individuals could help to shape stories so that they’re from the perspectives of Indigenous people themselves,” she says. “That was really meaningful.”

She also worked at the Longyear Museum of Anthropology with Professor Carol Ann Lorenz, from whom Kelly learned about exhibition and collections care. “It truly fostered an interest for me to blend my educational work with museums,” Kelly says.

After earning her MAT at Colgate, Kelly taught high school social studies before joining the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor as curator of education. It was there that she began her involvement with the Wabanaki studies curriculum, which she continues today. Maine passed a law in 2001 that requires schools to teach the history and culture of its Native people. At the Abbe, Kelly co-curated an exhibition on porcupine quillwork art by the Mi’kmaq artists, led classroom workshops, and helped develop a children’s performance that centered Wabanaki storytellers’ creative vision.

Her equity and inclusion work at the Children’s Museum and Theatre of Maine also involves community building, even with those who live farther away in the state. “We’ve expanded our geographical reach significantly within Maine, which was a huge goal of ours,” she says.

“There are certain parts of the museum where stories highlight community members we’re trying to reach,” Kelly adds. A current exhibition brings to life the book Beautiful Blackbird, by Ashley Bryan, a celebrated African American artist and storyteller from Maine. With the message “Black is beautiful,” the exhibition tells Bryan’s story, but also the impact he had on illustrators of color. “We want people to see themselves reflected as vital members of our community and leaders with important stories to share.”

Kelly considers herself a social justice educator who hopes to contribute to what she calls “a curriculum for dignity,” which includes respecting “the people in our content” and “looking for those voices that have been silenced.”

She sees museums as a place to elevate those voices. “[We] need these spaces to connect and have dialogue,” Kelly says. “Museums are a place where we can tackle these big issues together, and a place to come around to ideas of what’s important to us in our communities. It’s also a space where we can create community and promote belonging work.”

On Campus

The museum studies minor — which brings together art history, history, and anthropology — has been offered at Colgate since 2017. Take a peek at the program today.

Two classes anchor the program curriculum.

Museum Curating (300)

The fall 2021 course was taught by Rebecca Mendelsohn, co-director of University Museums and curator of the Longyear Museum of Anthropology. Nine students curated an exhibition for the Longyear that was focused on the theme of music; they were involved in every step of the process, from concept to installation. Beyond the Beat: Explorations in Music and Culture opened in February and runs until December. “The exhibition is about teamwork,” says Ray Zhang ’24, a history major and museum studies minor. “I also had the chance to explore my own interests in different themes and design my own plans to attract an audience’s interest,” adds Zhang, who worked on a case displaying Central and West African instruments that were decorated with human forms. In addition, there was a curator contribution case, in which students lent a piece representative of themselves. Zhang, who is from Ningbo, China, contributed a gourd instrument from his country, called a hulusi. In fall 2022, the Museum Curating course will be based at the Picker Art Gallery and will be taught by Nick West, co-director of University Museums and curator of the Picker.

Intro to Museum Studies (120)

Highlights from the spring 2022 course, taught by Professor Liz Marlowe:

→ Visiting the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica

→ A field trip to New York City, spending time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. There, students learned how to do a critical museum review. Marlowe explains: “They’re in a frame of mind where they’re not just learning what the museum is trying to tell them, but they’re also trying to understand the institution on a deeper level: how it engages with its community, how transparent it is in the kind of information it gives in its labels, who its target audience is, and how attuned it is to current directions in the field in terms of community curation (i.e., bringing in community members to be part of decision-making processes rather than being top down). We talk about a lot of the shifts that have been happening, thinking around issues of museum ethics and how actively museums are engaging in those conversations and how much they’re actually changing their practices based on those new interests in the field.”

→ Topics covered throughout the semester: the history of museums, museum architecture, museum policies, repatriation, colonialism, and decolonization

Current museum studies minors: 10

“It draws students from across campus: We’ve had biology majors, history, classics, peace and conflict studies, [among others],” says Professor Liz Marlowe, director of the program. “That’s the exciting thing about it — it’s bringing in a whole constituency that wouldn’t ordinarily engage with the arts or with museum culture. As the Middle Campus project grows and develops, we’re hoping that museum studies will be a really dynamic piece of that initiative and will get students from all different majors involved with that part of campus.”