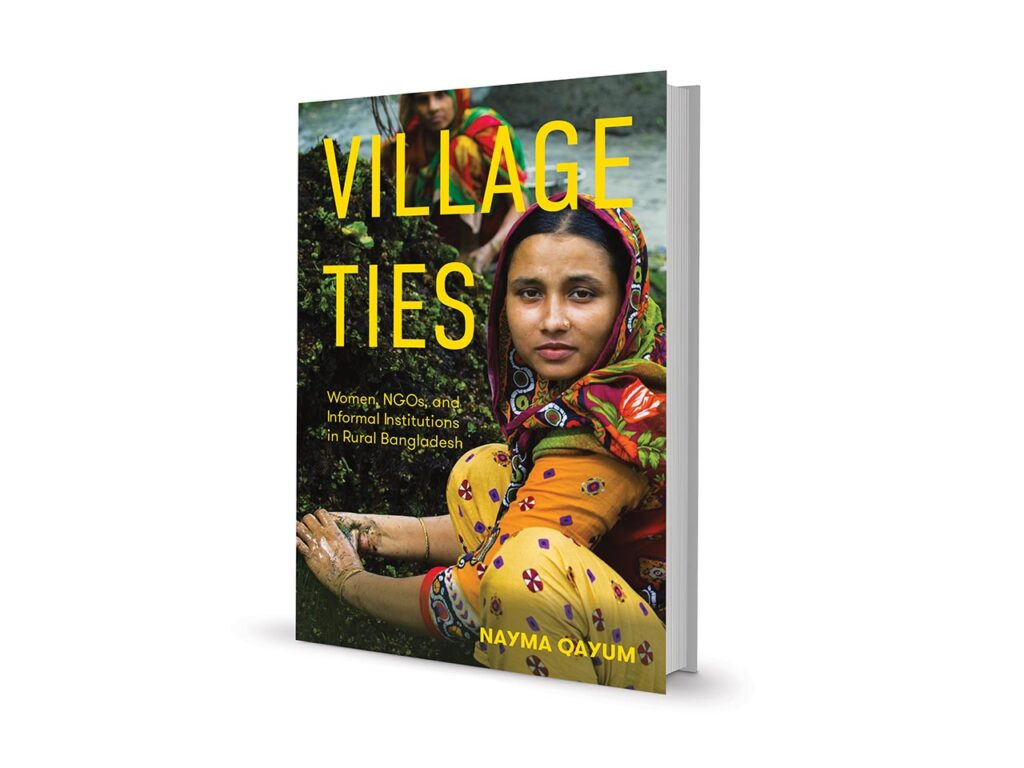

Returning to her home country of Bangladesh to conduct field research, Nayma Qayum ’02 studied issues such as domestic violence, child marriage, and dowries — illegal practices that continue as social norms — and how women-led grassroots organizations are stimulating change in their communities. She focused on Polli Shomaj (PS) — a grassroots program run by the development organization BRAC — which she views as a model for other organizations, “to show how the women of PS negotiate with state and society to alter the rules of the game,” as explained in her new book, Village Ties: Women, NGOs, and Informal Institutions in Rural Bangladesh (Rutgers University Press, 2021). Here, Qayum, who is an associate professor of Asian studies and global and international studies at Manhattanville College, discusses her findings.

I knew I wanted to look at informalities — the things that happen behind closed doors. We uncovered a lot of data that looked at why, for example, child marriages were happening and what these [women-led grassroots organizations] were doing to push back against them.

In the process of writing my book, I started looking at: How do you change social norms? How do you change human behavior? And how do you change the expectations around women’s behavior? Because that is huge.

There are all these non-government organizations training people about domestic violence and child marriage (Bangladesh has one of the highest rates of child marriage in the world.). For example, many organizations, including BRAC, run community-level workshops for young people and their families, sharing information and leading discussions on the adverse consequences of these practices. But these practices still exist. I wanted to study instances where actual social change was happening.

I studied changing social norms in three areas in the book. First, how the members of Polli Shomaj shifted the ways in which services are distributed in rural society. Welfare goods often come to the local government, but the ways in which they distributed [these goods] can

be very ad hoc … with so few resources and so many poor people, resources often went to people who were connected to the local government or had abilities to bargain. [The PS] groups now make a list of people who they think are the most deserving candidates in the village; they shifted expectations around who should get it. In many ways, they hold these officials accountable and many of the people on the PS group’s list received goods in these areas.

The second thing I looked at was legal issues: child marriage, dowries. The [PS] goes to try to negotiate with the families first. They’ll provide information, saying, ‘This is illegal. You shouldn’t do this.’ If that doesn’t work, sometimes they’ll make these issues public and put pressure, showing up in a large group and having the conversation outside of the person’s house. And if all else fails, they might threaten to call the police.

The third area I looked at was women being elected to local government. Bangladesh’s local government has quotas for electing women officials, but often the women who fulfill those quotas belong to the rural elite. So when members of Polli Shomaj campaign to have one of their members or somebody who’s poor elected, it shifts expectations that not only women can be in local government, but also poor women can be in local government.

The larger message is: How do you change expectations? What the political science literature tells us, and also what I found, is that you do it by establishing new expectations.

I’m hesitant to say, ‘These are permanent, and society’s going to change forever.’ But I think it gives us a glimpse into how institutional changes can happen even as we recognize that such changes take so much time. Change is not easy. You go five steps forward, two steps back. And sometimes you end up in unexpected places. But these stories show that institutional change — shifting social norms — is possible.

Qayum lived in Bangladesh until the age of 14 when she went to boarding school in India. At Colgate, she majored in political science. “[This] was my coming home in a way,” she says. “The journey of writing this book was a very reflective exercise for me. I got to travel to places where even my family members who lived in Bangladesh all their lives haven’t been. The fact that I got to meet and live with and talk to people all over Bangladesh made me realize the country is so big, and there’s so much diversity.”