In Mechanicsville, a neighborhood just south of downtown Atlanta, poverty reigns. Severe economic decline, caused in part by the construction of Interstate I-75/I-85 in the mid-20th century, combined with population migration, devastated the area. As a result, residents today struggle to pay bills and feed their families — and they deal with insurmountable stress and trauma. For those raising children, the burden becomes greater.

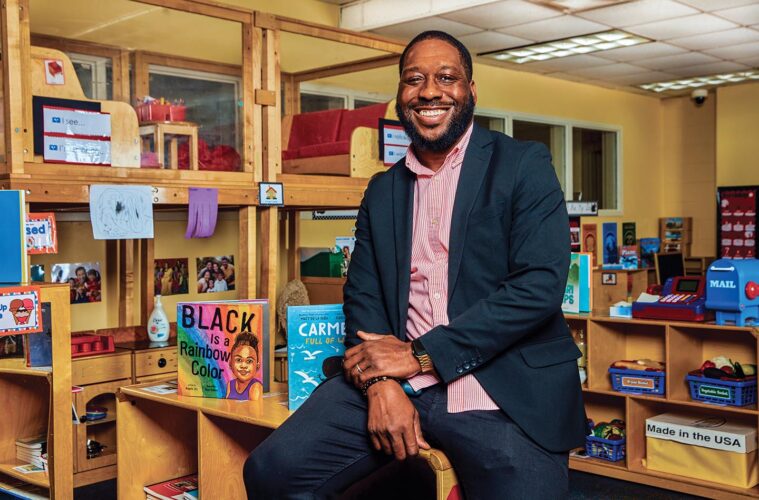

“Oftentimes inner city kids who live near or below the poverty lines go home to a family that’s struggling,” says Gemorial Johnson ’05, director of Educare Atlanta. The school serves low-income children in Mechanicsville, and Johnson is seeking to change daily life for parents and children in the largely underserved community.

“You have a child who has this great school environment, who goes home and all of the great experiences they had during the day get wiped out,” he says. “Sometimes families are not sure where they’re going to live the next month,” Johnson says.

To make that transition from school to home life easier on its 200 students,

who range from infants to age 5, Educare employs the two-generation model for families. This means providing equal support to both parents and children. Parents have access to counseling services, financial literacy courses, and better employment opportunities. The local food bank brings shelf-stable items directly to the school, so parents can take what they need while picking up their children. And, health care for children is often available at the school during school hours through Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, which houses an RN on site at the school. Therefore, parents can focus on working during the day.

Students receive individualized attention at Educare, thanks in part to its partnership with Georgia State University (GSU). Research students from GSU frequently come to Educare to observe and interact with the children, tracking each child’s educational growth. They periodically give their findings back to Educare, so the data can inform changes to the curriculum. “It allows us to see which children are struggling,” Johnson says. “We can take a deeper look into what’s happening with a child.”

For Johnson, going into work each day isn’t just about making the lives of children better. It’s also about reclaiming his own childhood. “I grew up in a community very similar to this one. I was able to get to Colgate by doing well in school, but also being an athlete,” says the sociology and anthropology major. “[After college,] I didn’t have the resources to be able to go out of the country and study anthropology. I needed to come back home and work.”

His backup plan was childhood education, so he started teaching at Sheltering Arms, which would later become Educare Atlanta, in 2005. He moved up the ladder, leaving the school in 2015 to take an assistant director position at Bright Horizons, another education center in Atlanta. In August 2021, he came back to Educare, this time in the top position. “This is coming full circle, being able to go back to a place where I helped start, helped build. [I’m helping to] make it better and have a bigger impact on children and families.”

He adds that because most of the school children and families are African American: “For the little boys here, or even for the young dads here, to see someone who looks like them in this position is a really powerful thing. That’s one of the things that makes me really proud.”