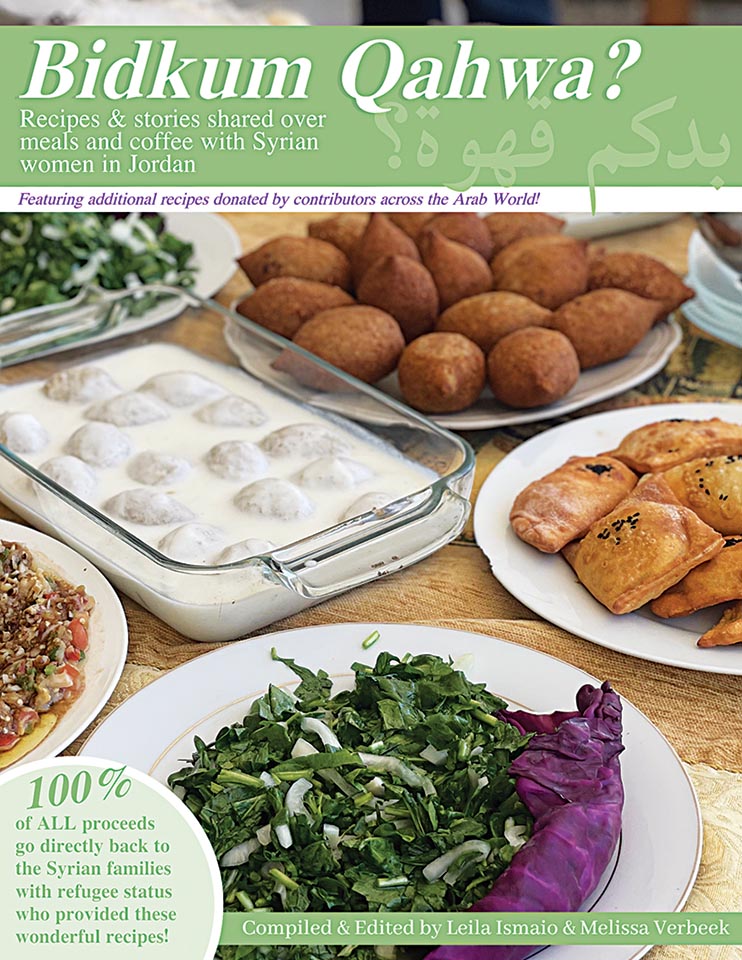

Two alumnae compile a cookbook of recipes from the Arab world, providing aid to women Syrian refugees in Jordan.

Heaping servings of dishes like grape leaves, lamb meatballs, basmati rice, and tabbouleh left Melissa Verbeek ’21 and Leila Ismaio ’21 stuffed after dinners at a Syrian refugee center in Amman, Jordan. Even the strong Turkish coffee that’s the customary conclusion to meals failed to rouse them, so they’d return to their apartment and nap.

Verbeek and Ismaio spent the summer helping Syrian women of refugee status; their work was supported by a Kathryn W. Davis Projects for Peace Grant. During their two months in Amman, they used the grant to create a children’s play space in one center, build a rooftop garden in a second center, and develop a digital cookbook that they began selling in September to provide financial aid to the women.

“Leila and I want to raise as much money as possible because we think that everyone deserves to live not only with the basic needs, but also comfortably and well,” Verbeek says.

The recipes in the cookbook were provided by the women at the second refugee center and translated into English by Verbeek and Ismaio. “Everyone had really cool ideas and they were super excited,” Ismaio recalls. Verbeek and Ismaio spent a day with each family to learn how to cook the dishes, take notes, and eat the meal together. “It was obvious when we started cooking with every family that that’s something they really enjoyed doing, and it was incredible to be a part of,” Ismaio says.

As is often the case with family recipes passed down through generations, cooking is done through instinct, so there aren’t exact measurements. In addition, the Syrian women are used to cooking for their large families. For example, one woman made 100 kibbeh — deep-fried pouches of ground lamb and beef. “They’d say, ‘4 pounds of flour,’ and I’d think, ‘How do we convert that into four servings?’” Ismaio remembers. “So it had its chaotic moments, but I think that was my favorite part.”

Verbeek adds: “I would be in the corner with my notebook writing everything as fast as I could. The notes are incomprehensible if you look back at them.”

Through the process, the two developed close relationships with the families. “It was more than just eating or picking a recipe, it was sharing my stories and their stories,” says Ismaio, who grew up with an Arabic background (her parents are from Libya).

Dinners would last hours. Sometimes the Syrian women would FaceTime with their families back home and include Verbeek and Ismaio on the calls. “We really got to know people through the process of cooking and then sharing Turkish coffee afterward,” Verbeek says.

End-of-the-meal Turkish coffee was a requisite part of the experience. Despite their achingly full stomachs and a general distaste for the beverage, the two Americans knew it would be rude to turn down the offer. The title of their cookbook, Bidkum Qahwa? — meaning “Do you want coffee?” in Syrian — is a nod to that experience. “The answer is always yes, even if you don’t really like coffee, because it’s the social way to gather and talk,” Verbeek explains.

The cookbook includes directions for how to make the thick, rich drink, along with a suggestion to add cardamom or coriander. The page is decorated with pictures by a woman called Um Amar, whose hobby is to photograph arrangements of her Turkish coffee.

Most of the recipe titles begin with “Um” — meaning mother — followed by the name of the woman’s oldest son. The authors explain this as well as other tidbits of information and anecdotes in the book.

“Something Melissa and I talked about while we were putting in these stories is we really wanted the book to center on who these women are, some of their passions, and what they’re excited about,” Ismaio says. “Obviously, they’re coming from a war-torn country, so there are a lot of really sad stories, but we wanted the book to reflect who they are and not the circumstances that have led them to be in the situation they are in. We wanted to highlight the strong women we met.”

They first met the women at the centers in 2019 during a study abroad program that focused on persons with refugee status and humanitarian action, specifically looking at the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan. (The nation currently hosts 668,000 Syrians registered with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.)

Verbeek and Ismaio had become best friends through their Arabic studies courses at Colgate — both majored in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies (with Ismaio adding a second major in peace and conflict studies).

During the study abroad program, Verbeek’s research project was inspired by her courses in educational studies (her double minor with psychology). She interviewed Jordanian and Syrian youth about the effectiveness of their educational system.

Ismaio’s research looked at the gaps in services from humanitarian aid organizations serving widowed Syrian women. The two students’ research projects often overlapped as they were interviewing the women and children at the refugee centers.

The issues they saw while doing this work inspired them to apply for the Projects for Peace Grant. “We did basic undergraduate-level research and weren’t really able to offer anything to the women, so we had them in our minds when we applied for the grant,” Verbeek says.

They received the award in 2020 but had to postpone their trip due to the pandemic. Returning to Amman this summer, Verbeek and Ismaio observed how communities have been affected. International funding assistance has been redirected to COVID-19 efforts, some of the women have lost their jobs, and many of the boys quit school to work to support their families. “The situation definitely has gotten worse,” Ismaio says.

From her 2019 research project, Ismaio learned that direct cash assistance is an essential service often overlooked by humanitarian aid organizations. That knowledge fed the idea for creating a cookbook and giving 100% of the proceeds to the Syrian women at the second center, which receives much less international aid than the larger center.

There are 28 recipes in the cookbook, most of which were provided by the Syrian women, but a handful are from the authors’ friends and Ismaio’s family (including her dad’s shakshuka, which the alumnae often made when living together). “The donated recipes are from other people across the Arab world to enhance the cookbook,” Verbeek says.

A “cucumbers of difficulty” rating on each recipe tells readers how much skill is involved. For a couple of the more complex dishes, there are links to videos showing, for instance, how to roll the grape leaves or form

the kibbeh.

A donation option on the website allows people to give and receive without purchasing the cookbook for $25. “If you donate any amount, we send you three mystery recipes,” Verbeek says.

Now they’re on to their next adventures. Verbeek received a scholarship to attend England’s University of Exeter, which has a well-known Arab and Islamic studies institute. Ismaio is studying for the LSATs with the goal of attending law school next year, and she is considering going into immigration or international law.