New research outlines how Oneida lands became Colgate

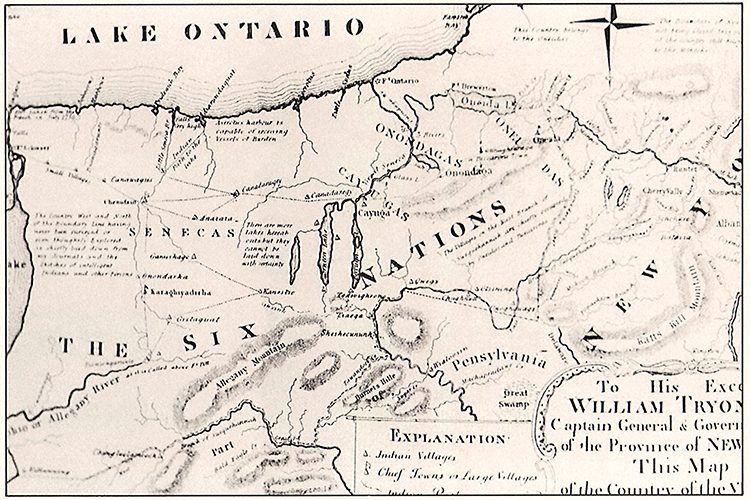

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Oneida people of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Nation and their ancestors had lived in central New York for millennia, in an area covering more than 6 million acres from the St. Lawrence River to today’s Pennsylvania border.

In observance of Colgate’s Bicentennial, the University’s Native American Studies Program commissioned Laurence Hauptman, distinguished professor emeritus of history at SUNY New Paltz, to research how the campus came to be situated on Oneida ancestral lands. Hauptman unpacked the complex account — including archaeology conducted by Professor Jordan Kerber (sociology and anthropology, Native American studies) and his student researchers going back to 1991 — in a detailed report.

Given its strategic location, the region’s land was coveted and contested by colonial, state, and federal officials; military officers; land speculators; and turnpike and canal developers. The Oneidas were drawn not only into negotiations for land cessions, but also wars.

After the Revolutionary War, prominent New York State families “tripped over their own feet,” Hauptman reports, competing with one another for Indian lands in pursuit of economic gains through settlement and commerce. And while Governor George Clinton had made promises to the Oneidas — that they and their lands would be respected, and he would enforce state constitutional law forbidding Indian land sales to individuals without legislative permission — he was soon breaking them.

With the Treaty of Fort Schuyler in 1788, New York State acquired 5 million acres for “safekeeping” through what Hauptman calls “a late–18th-century version of a Mafia protection racket.” Oneida Chief Good Peter “and his supporters were caught — on one hand fearing avaricious land speculators colluding with some of his people; and on the other, fearing the likelihood that the state government would not protect them and allow numerous non-Indian settlers to pour in and trespass on Oneida territory” — so they reluctantly conceded to Clinton and signed the “accord.”

By the early 1790s, acts of the state legislature provided for the survey and sale of the lands “acquired” at the Fort Schuyler treaty. William Stephens Smith — son-in-law of Vice President John Adams — purchased six of these townships. Soon after, Smith sold parcels within one township to Dominick Lynch of Utica, including a 123-acre parcel south of what would become the village of Hamilton. Lynch, in turn, sold that farm to Samuel Payne.

With that purchase, Payne and his wife, Betsey, became the first non-Indian settlers in the area, in 1794. Arriving the next year, Payne’s brother Elisha purchased a nearby lot, founding what was first called in 1796 “Payne’s Settlement,” now the Village of Hamilton. The brothers went on to join 11 others in founding the Baptist Education Society of the State of New York. In 1826, Payne sold his land to the society for half its value — $2,000 — to serve as the campus for the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution, which would become Colgate.

The archaeological evidence so far suggests that Oneidas did not establish a village site on lands that became Colgate University. Native Americans employed a temporary campsite in the vicinity of Hamilton off and on for thousands of years into the 1600s, but as yet, according to Hauptman’s report, “no evidence of a permanent village site, no palisaded structure, and no longhouse residence have ever been found” in the village or town.

Although eventual possession was made possible by the state treaty with the Oneidas at Fort Schuyler, records indicate that none of the original 13 founders of the Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution had participated in the councils in 1788, nor in other treaties with the Oneidas.

And yet, Colgate’s campus is, Hauptman points out, part of the Oneida territory that “allowed New York … to become the Empire State. To Albany politicians and to the emerging capitalist class … the lands in Iroquoia were … vital for the building of a transportation network that would further land sales and populate New York’s frontier. The sale of Hodinöhsö:ni´ [Haudenosaunee] lands provided the very capital for future investment.”

Read a fuller version of the story here.