Thea Traff ’13 shares her experiences photographing famous faces, including Lily Gladstone, Mick Jagger, and President Biden.

Thea Traff ’13 can easily rattle off the elements of a “good” editorial photograph. Readability, she says, is foremost. “You have to immediately understand what you’re looking at.” Also, repeating shapes satisfy a particular itch in the human brain. Layering is important, too — drawing the viewer’s interest to both the foreground and background to make an image more dynamic.

And then there’s the light.

“You can have an amazing subject doing an amazing pose with a great expression, but if the light’s not right, it’s not going to be a good photo,” Traff says. “The light is everything.”

But, of course, there’s also something else — something that, even when all the boxes are checked, separates a nice picture from a striking piece of art. That requires skill. A good eye. Or “an understated yet sophisticated sense of nuance,” as Professor of Art and Film & Media Studies Lynn Schwarzer puts it. “Thea always had it.”

In the 11 years since graduating from Colgate with a degree in art and philosophy, Traff has emerged as a stand-out talent in the editorial photography world, making her mark as a photo editor for the New Yorker and TIME magazines, and most recently, as a freelance photographer, with her work appearing in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, and Rolling Stone. Some of her recent subjects: of-the-moment pop singer Sabrina Carpenter, fashion icon Diane von Furstenberg, and Cyndi Lauper.

A Minnetonka, Minn., native, Traff enrolled at Colgate interested in photography. Drawn to Colgate’s small-town feel — “It reminded me of home” — she found a mentor in Schwarzer and thrived within the arts curriculum, which exposed her to “sculptors, painters, and installation artists in addition to other photographers,” says Traff. “I benefited from being immersed in all these art forms and learning how they play into photography.”

At Colgate she began to find her quiet, contemplative style. Her senior project — a series of minimalist landscapes in and around Hamilton — demonstrated her “thoughtfulness and restraint,” says Schwarzer. “We talked for hours about details, like the snow and the fog in [one of her landscapes]. She went to that particular landscape again and again just to see the subtle changes in the light. ‘Well, what does it look like at 10? What does it look like at 2? What happens if the contrast is a little different? And then which one gets you to look hardest at what it is?’”

Also during her senior year, Traff signed up for Career Services’ Day in the Life program, which paired her with Christina Cahill ’85, then a photography editor for Reportage by Getty Images. Cahill welcomed Traff into her New York City office for several days, eventually connecting the young photographer with the photography team at the New Yorker. After an interview and a review of her portfolio, the director of photography offered Traff a job as web photo editor; she started immediately after graduation.

“[Cahill] really gave me an in into the editorial world in New York and set me down this path,” says Traff. “I owe everything to her.”

As photo editor, Traff initially felt overwhelmed. “I was working for the New Yorker’s website, and for a time, I was the only person choosing the visuals for all the stories,” she recalls. “It’s a news website, so I was working seven days a week and expected to be responsive to news 24/7,” says Traff, who likens her five-year tenure at the New Yorker to “editorial photography graduate school.”

By 2018, Traff moved into a new role with TIME, as a photo editor for the print magazine and the website. There, says Traff, she further developed as a storyteller, determining how to create portraits that convey emotion in a fresh way. But all the while, Traff felt herself pulled back behind the camera.

“So often as a photo editor, I would get shoots back and [the subjects] would have kind of a blank, thousand-yard stare,” she says. “I felt like the photographers could be pushing the boundaries a bit more.”

In 2020 she returned to making images of her own, incorporating all she’d learned at the photo editor’s desk into her approach. She also began to shoot almost exclusively in black and white — an attempt to stand out during a time when most editorial photography veers toward loud and vivid color.

“The trend of the past few years has been shooting in a kind of filmic, very colorful, little bit retro way,” she says. “I want to create images that feel timeless.”

Guided by the work of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, Traff often asks her subjects to mimic reference images — sculptures, for instance, or photos of dancers. The idea is not to copy the reference, but to inspire that same emotion in a slight tilt of the head or hint of a smile.

“I try to evoke emotion through a gesture or a facial expression in hopes that it brings some emotion out of the viewer,” she says.

In an interview with Colgate Magazine, Traff shared the stories behind some of her favorite recent shots and the lessons she’s learned — about photography, creativity, and herself — along the way.

Rachel Weisz

The New York Times Magazine, April 2023

“All the stars aligned for this shoot. Rachel and her team gave me nearly three hours, which almost never happens — with some celebrities, I’ll have just two minutes. But she was so patient and trusting and open for collaboration.

“The [accompanying] New York Times Magazine article was about her TV series Dead Ringers, in which she plays twin doctors in a maternity clinic. It’s a highly sexualized show with themes around abortion, sex, and pregnancy, so for references, I pulled a lot of Renaissance paintings that use fruits to hint at sexual ideas. You can see in my work that I like to use hands. I think they’re a nice shape and can create something visually interesting. I’ll ask [subjects], ‘Is there anything with your hands that feels natural around your face?’ Rachel just got it and embraced the ideas.”

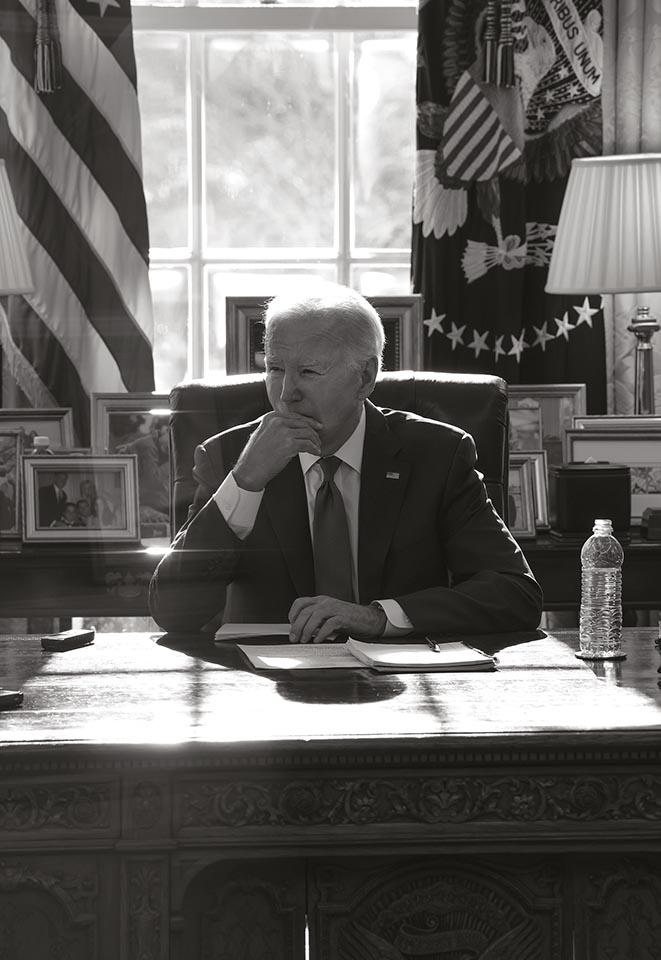

President Joe Biden

The New Yorker, January 2024

“I got the call about this assignment on Jan. 16 at 3 p.m., and I had to be at the White House the next day at 11 a.m. So I had no time to plan, to brainstorm, or even to organize an outfit for myself. I was told that the writer and I would get 30 minutes with [Biden] in the Oval Office. So I grabbed my suit jacket and pants that did not match, picked up my cameras and lighting equipment, and got on a train to D.C. I was actually still on the train when I learned I wouldn’t be able to use any lighting in the Oval. No flash. I don’t know if that’s because it would be too distracting to [Biden] during the interview, but I also wasn’t able to direct him or pose him in any way. So that was an unexpected challenge. When I arrived in D.C., I ordered an Instacart delivery from Lowe’s — a few pieces of fabric and a pane of glass. My thinking was that, if I can’t use a flash, sometimes shooting through objects makes an interesting effect. I’m always trying to make portraits a bit more interesting and elevate them in some way.

“In the end, I only had about 10 minutes with him, and my favorite photo was shot through that piece of glass; that little flare to the left of his body is a reflection. The New Yorker chose to run it in color, because the editors felt like a black-and-white photo would be too somber and heavy. The whole experience was a big adrenaline rush, and I was proud of the result. Sometimes when the circumstances are so limited, it takes a bit of the pressure off of me. It’s easier to know I did my best.”

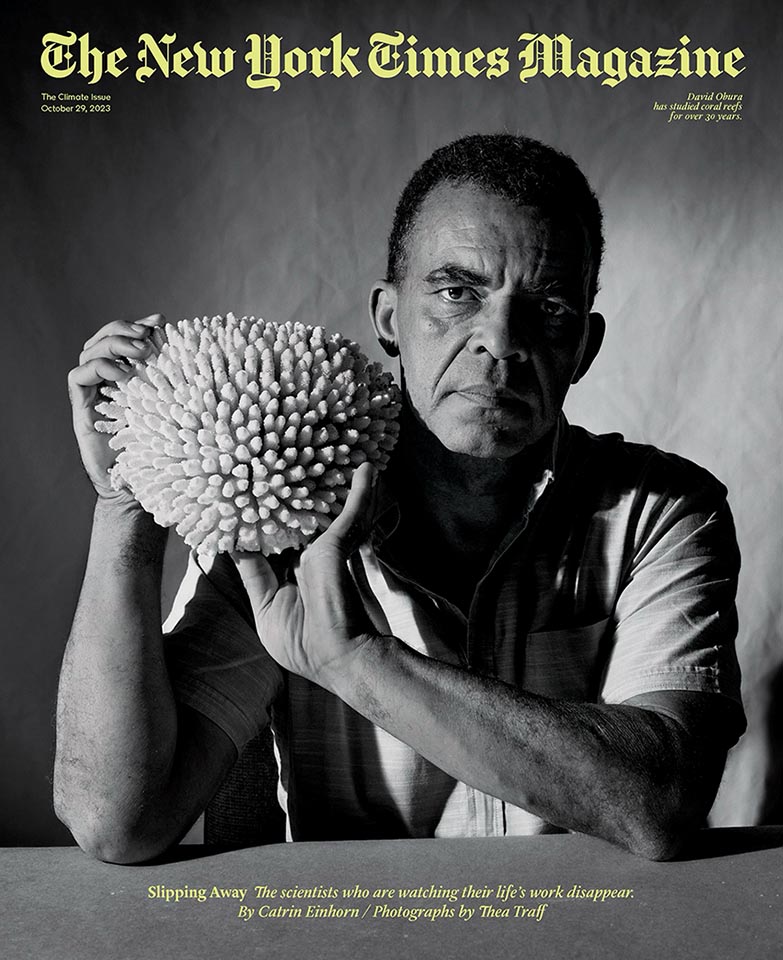

Climate Scientists

The New York Times Magazine, October 2023

“This was the biggest shoot I’ve ever done in terms of time granted and resources. The piece required a lot of solo travel — from Chile to France — to photograph scientists who are studying different aspects of the earth that are affected by climate change.

“To get the shot of [coral reef scientist] David Obura, the plan was for me to go to Kenya for 48 hours and shoot him in Mombasa, where he lives. So I packed my equipment, my whole lighting setup with my light stand and my backdrop, one change of clothes, and a lot of bug spray. I got to JFK, and I’m in the Kenya Airways check-in line, and they asked for my passport and visa. I thought, ‘Oh my God. I don’t have a visa.’ So I waited at JFK for four hours trying to see if I was going to be able to make it without the visa. That didn’t happen. I got in touch with David to tell him, and he was just incredibly patient and excited to be a part of the story. He told me that that weekend, he was going to be in Paris for a day to attend a conference.

“The idea behind the shoot was that each scientist would be holding the object of their study, and for David, that was this native piece of finger coral. He had a contact at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and they happened to have a piece of the coral he studies. So I got on a plane and headed to Paris. I had about 20 minutes with him at the museum, and he was really lovely and open to my references and sense of direction. We got the shot, and then he got on his train and left. That portrait ended up on the cover.”

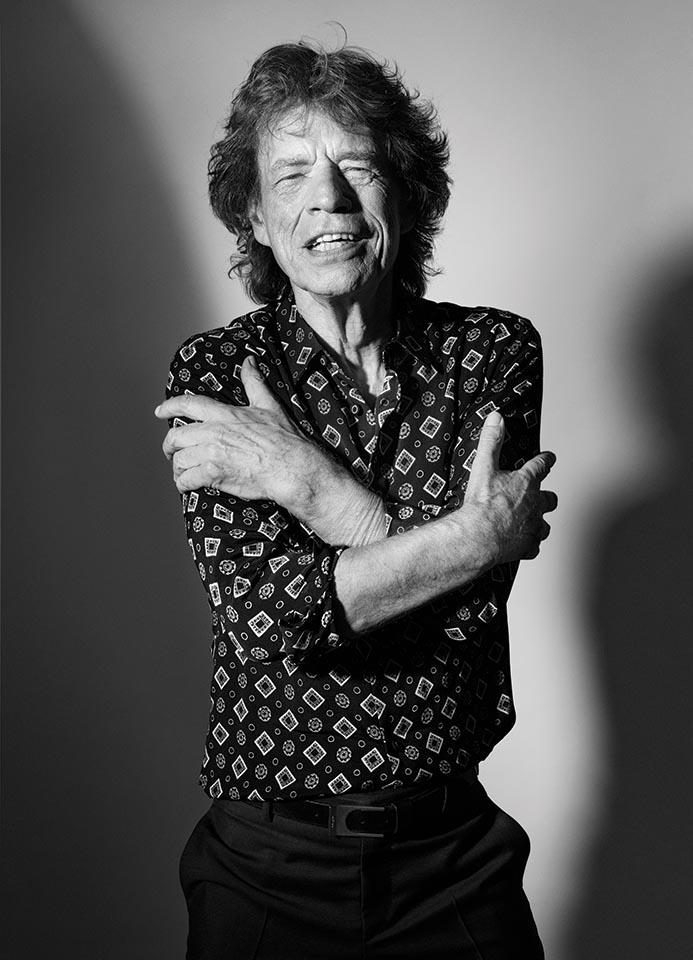

The Rolling Stones

The New York Times, September 2023

“This was an awesome shoot and exactly what you’d expect from [the Stones]. I shot them all separately and Mick, especially, was so lovely. [He said] ‘Hi, Thea, it’s nice to meet you. I looked at your website. Would you be OK if I wore this? If not, I have a second option.’ We had our full 20 minutes, and he asked, ‘Do you feel like you got what you need?’ Just very patient and kind.”

Lily Gladstone

The New York Times Magazine, January 2024

“This shoot was for a profile of Gladstone, who had just been nominated for an Oscar for Killers of the Flower Moon. Knowing she is Native American and how much it connects to her role in the film and her work as an actress, I wanted to convey some element of nature in the shoot, even though we were in a studio. I used this metallic reflective sheet, and I pointed the light down at it so that the sheet reflected her face, like a water reflection. I cropped it and played with the light a bit in Photoshop, but I loved the result.

“Most people wouldn’t expect this, but actors can feel really awkward during photoshoots because you’re photographing them — not a character they’re playing. So I’ve found that giving them a role to play for a shoot can make them come alive a bit more in front of the camera. If I’m shooting someone and it’s pegged to an intense film that’s coming out, I’ll say, ‘I’d love to convey the intensity and the drama of the film through your expression. Is there anything you can give me in that world?’ Sometimes my ideas are shot down, and it’s taken a lot of practice to remind myself that that’s part of the process. In fact, I tell myself now, if I’m not shot down with one idea, I haven’t pushed hard enough creatively for that shoot.”