She brings readers into the lives of blues musicians in her new book, Deep Inside the Blues.

One hot summer day in 1997, Margo Cooper ’76 found herself at a picnic in Gravel Springs, Miss., the smell of stewed goat meat wafting around her. The annual event was held by hill country music legend Otha Turner, who was known for his spirited, traditional fife and drum music. Friends, neighbors, and Turner’s grandchildren played drums alongside Turner’s fife, while community members dabbed sweat from their foreheads. Cooper would photograph Turner that day, planting the seeds of a friendship that would continue until the artist’s death in 2003.

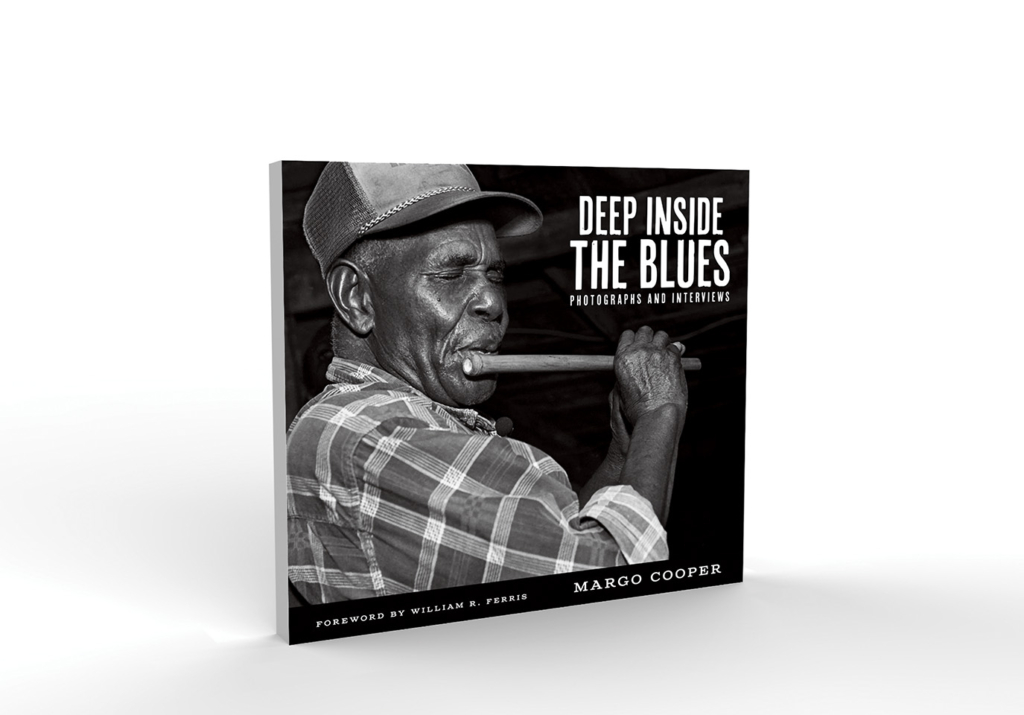

Cooper’s connection to Turner and his legacy didn’t end when he passed away. Turner’s portrait appears on the cover of Cooper’s latest photography book, Deep Inside the Blues (University of Mississippi Press, 2023), incorporating 160 photographs of and 34 interviews with musicians.

That day at the picnic, Cooper also met Turner’s 7-year-old granddaughter, Shardé Thomas, who is now a three-time Grammy nominee (and she’s now in charge of the annual goat festival). And, through the years, Cooper met a host of other blues musicians, like LC Ulmer, Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson, and Sam Carr. She fostered these relationships, keeping in touch with the men until their deaths.

Throughout that time, Cooper recorded her conversations with musicians from the region and nearby areas, which she transcribed and submitted as oral histories for the Mississippi-based magazine Living Blues. Concurrently, she was working as a court-appointed attorney and guardian ad litem in New Hampshire’s juvenile and family courts, and she would travel to the Magnolia State several times a year: “Although I didn’t have the time, I just said, ‘I will make the time to start working with musicians and writing their stories of their life, in their words,’” she recalls.

Cooper has been a fan of the blues since she was a teenager. In her early years as a solo law practitioner, the Colgate sociology and anthropology major would hang around blues clubs near Boston in the evenings, and sometimes she’d photograph the performers as a side gig. Many of those musicians were aging artists who’d grown up in the Jim Crow South and moved to Chicago during the Great Migration. Recognizing this history, Cooper wondered: “What was that experience like? What were the stories behind the music?

“I decided the only way to find out was to go to Mississippi,” she says.

The decision to travel down South to hear blues music and, by happenstance, attend Turner’s picnic would begin a lifelong journey of chronicling the lives and performances of blues artists. “Remembering is a duty,” she says about her work. The musicians became like family to Cooper, and they let her into their inner circle, so it’s her responsibility to make sure their lives are remembered. “In some instances, I worked with a musician over the course of several years before their story was finalized, and I always remained in contact and would visit those musicians whom I wrote about,” Cooper says.

“The friendship would never end.”