Colgate’s iconic allées began as functional additions to address the needs of a blossoming campus. Now, the University has the Third-Century Plan to preserve and extend their beauty.

A December wind is blowing through campus, swirling the first snowflakes of the impending winter. Trucks towing cherry pickers and wood chippers turn onto Oak Drive. They carry workers in coveralls, wearing gloves designed both for warmth and protection against splinters. These contractors are from the University’s arbor company, and they are here to address safety issues along the iconic entryway to campus: They will take down eight red oaks that have reached the end of their lifespan and are in danger of falling.

Landscape Project Manager Katy Jacobs, Colgate’s on-staff tree expert, is focusing on paperwork in her warm Merrill House office. Her reasons for avoiding the outdoors have more to do with the saws than the weather. She knows that removing these trees is a last resort, after cabling of the canopy, pruning, and injections of nutrients failed. She also knows these trees will be replaced immediately — by oaks that will still be growing strong when the Class of 2022 arrives for its 50th Reunion. This is what it means to steward Colgate’s beautiful campus. Yet she waits until she’s sure the first cuts into the canopy are complete before she steps out for a progress report.

Looking past James B. Colgate Hall and following the sweep of the hill down toward the old stone bridge, she sees “a smile with a missing tooth. It’s prominent.”

The Forest for the Trees

President Brian W. Casey often refers to Colgate as “a place set apart for the purpose of academic inquiry.” The aesthetics are not a luxury, but rather an intrinsic part of the University’s distinctive liberal arts experience. Just as academic departments regularly scrutinize the currency and rigor of their curricula, staff members and administrators carefully review and steward the campus environs. They map the place as a whole, and they log the locations and conditions of each pipe and wire, the health of individual trees.

Prioritization is key when there is so much to maintain, and it relies on a holistic approach, according to Jacobs. “It begins with the safety of the campus, then we look at functionality. People should be happy and relaxed, not worried about how to get where they’re going. So we are always asking, ‘What takes away from the awe of campus?’ because these things can be resolved.”

If you address the first two priorities of safety and functionality, Jacobs believes that you are well on your way to bolstering the third: that sheer beauty. History is on her side.

The aesthetics are not a luxury, but rather an intrinsic part of the University’s distinctive liberal arts experience.

That Old Saw

Kiss someone on Willow Path and you will end up married. This kind of lore — though a pleasant and important source of tradition — obscures some basic truths inherent in the history of both Colgate allées.

“A lot of people assume that the willows were part of the original construction [of Willow Path], and that’s simply not true,” says Professor of Art and Art History Robert McVaugh, who has made a close study of Colgate’s physical transformation through the centuries. “The willows were a way of completing something, which evolved from other needs.”

The need for Willow Path was originally articulated in the 1870s by a faculty committee, whose members wanted a safer, easier way for professors and students to walk from the quad down to the new academy building — locations separated by a muddy, marshy swath of pasture. The unadorned walkway they were given ran straight down the hill to Broad Street. It included a low wooden bridge across Payne Creek to prevent scholars from mucking their boots in the water, which carried runoff from the slaughterhouse at the corner of Hamilton Street and East Kendrick Avenue. Fredrick Law Olmsted’s campus sketch from 1883 labels this “the Present Path.”

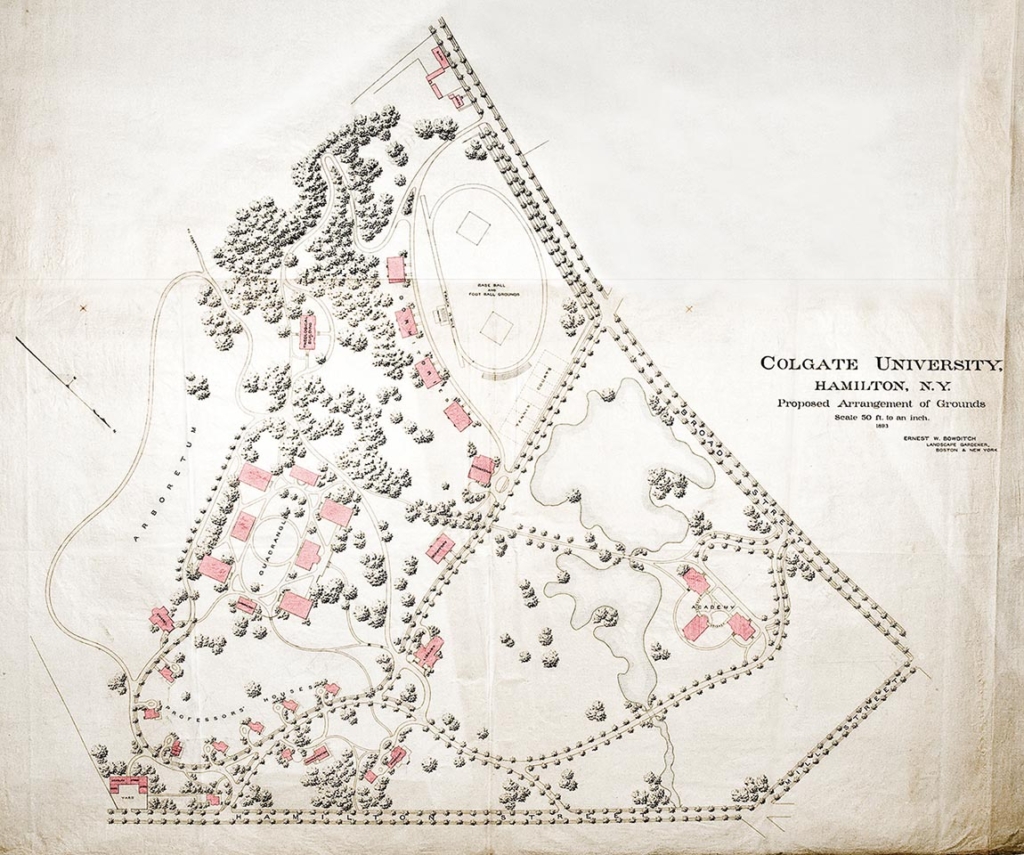

Years passed. Campus plans were drawn up and shelved until the 1890s, when the academy needed a sewer system. Ernest W. Bowditch, the University’s new campus planner, decided to use Whitnall Field as the leaching area. He would run the sewer pipe from modern-day Oak Drive to the Present Path. The pipe would then turn left and follow the path across the creek before banking right toward the leach field. But he needed a bit of elevation so the physics would work in his favor and the fluids would flow properly

In collaboration with Professor James Taylor, head of buildings and grounds, Bowditch had a lake dug in the pasture next to the walk. He took the clay-heavy soil from the hole and used it to bury the pipe and elevate the walk, making it level with the academy lawn. He constructed an elevated stone and iron bridge to replace the earlier, creek-level version and attached the pipe discretely beneath, snaking it across the run.

Even with such a beautiful new lake and stone bridge, Taylor continued the practice of planting random trees from the top of campus down along the plain for decoration. It wasn’t until the spring of 1906 that Taylor would embrace a signature embellishment of the era: paired trees along the Present Path. Thus, Willow Path.

McVaugh sums it up this way: “We needed a path that takes the academy students from the hill down to the academy. We needed it to be direct. And then there was the elevating, which was related to the operations of the infrastructure.”

But it sure is beautiful, especially with the lights on the willow trunks.

Driving it Home

Olmsted’s 1883 plan noting the Present Path included a carriage drive to convey vehicular traffic from the academy building to the quad. He suggested it for several reasons. First, in keeping with his approach to New York City’s Central Park, it kept pedestrians and vehicles on separate paths that never intersected. Second, it fully embraced the north-south opportunities offered by the Colgate Academy to a campus that had long been oriented on a rigid east-west axis.

Jacobs might call this safety first, then functionality. Or, as historian McVaugh tells it, “Olmsted is the one who said, ‘You are no longer a campus that is isolated on a hill. With the addition of the academy, campus sweeps from the hill to the plain, and you need to develop the continuity of that.’”

Versions of Oak Drive appear on numerous plans, including Bowditch’s 1893 effort. But it wasn’t until 1913, when the Colgate Academy closed and was transformed into the University’s administration building, that a carriage path from the top of the hill to the bottom became a true need.

“That completely changes the internal dynamics of the University,” says McVaugh. “The president was down on the plain, and there’s a constant movement back and forth.”

So the University pulled Olmsted’s and Bowditch’s various plans from the shelf and constructed the elevated road that still enters campus at the corner of Broad Street and Kendrick, crosses a stone bridge, and arcs toward James B. Colgate Hall. It circles the hill to the southeast then dead-ends just beyond the Coop — deviating from Olmsted’s original vision for a full loop around campus. As early photos of the stone bridge show, paired trees followed a few years later. The architects who were immediately responsible for the views we enjoy today both died without seeing their vision in its full glory.

It’s More Than Academic

The Colgate Academy is gone, and the stone bridge on Willow Path no longer serves as a fig leaf for a sewer pipe. The president and University administration are back atop the hill, and Oak Drive is traveled both by horseless carriages and cross country teams. The primary needs that drove the creation of these two landmarks are now interesting asides in University history, but the beauty remains — a striking first impression for visitors, an inspiration for the on-campus community, a source of nostalgia and pride for alumni. It even has its own section in the Third-Century Plan.

But trees, like humans, have a lifespan. For red oaks in a developed environment like Oak Drive, it is about a century. For coral bark willows, which were last planted along Willow Path between 1989 and 1991, it is around 40 years. Those who care for Colgate’s environs today have the privilege and the challenge of being on duty as these time frames intersect on campus. They must address immediate needs while keeping an eye on the legacy they pass along to the next generation. “Colgate is beautiful, and you have an obligation to steward that beauty,” says Casey.

Shortly before the arborists rolled onto campus last December, the president sent a message to the entire Colgate community, outlining ambitious plans for Oak Drive and Willow Path restoration. They include replacing those eight trees — the missing teeth — with 21 new red oaks to fill recent gaps, address long-vacant spaces, and lengthen the allée to Broad Street. Memorials to the victims of a November 2000 crash on Oak Drive will be reestablished. An additional 40 trees of various varieties will be planted along the access road to Hamilton Street and in the shadow of Merrill House, extending the spirit of Oak Drive all the way to James B. Colgate Hall while enhancing biodiversity in the area. New sidewalks and lighting will create a stronger connection between campus and the village of Hamilton while ensuring pedestrians and vehicles all navigate safely. This work will be funded through a gift from Peter Kellner ’65, who was inspired to give when he read the president’s message.

Willow Path presents its own challenges. The University has begun planning in earnest for replacements while pruning, cabling, and feeding the current trees. Local nurseries are unable to supply the required number and size of coral bark willows, so Colgate staffers like Jacobs are exploring options that include setting aside nursery space on University property or engaging with a local nursery to cultivate them. By taking immediate action, the University will be ready when the inevitable moment of removal arrives.

Like many other campus infrastructure projects, restoration of Oak Drive and Willow Path is a matter of safety. Falling trees are dangerous, and sidewalks are a must when drivers and walkers are mere feet apart. Then, there is function. Do the roadways and pathways lead you to your destination in a logical, helpful manner? The slaughterhouse might be gone, but the annoyance of a wet sock is timeless.

Yet beauty is no longer a mere byproduct of need, as it was in the days of Olmsted, Bowditch, and Taylor. It is that third priority, constantly on the minds of Casey, Jacobs, and fellow campus planners — an integral part of the distinctive place that is Colgate.

“I’d like to think, particularly with Oak Drive, we’re not just stewarding it,” Casey says. “We’re making it bigger, and in some ways this is a metaphor for what Colgate is doing through the Third-Century Plan. Not only are we going to take care of things; we are also going to address weaknesses and make Colgate bigger and better.”