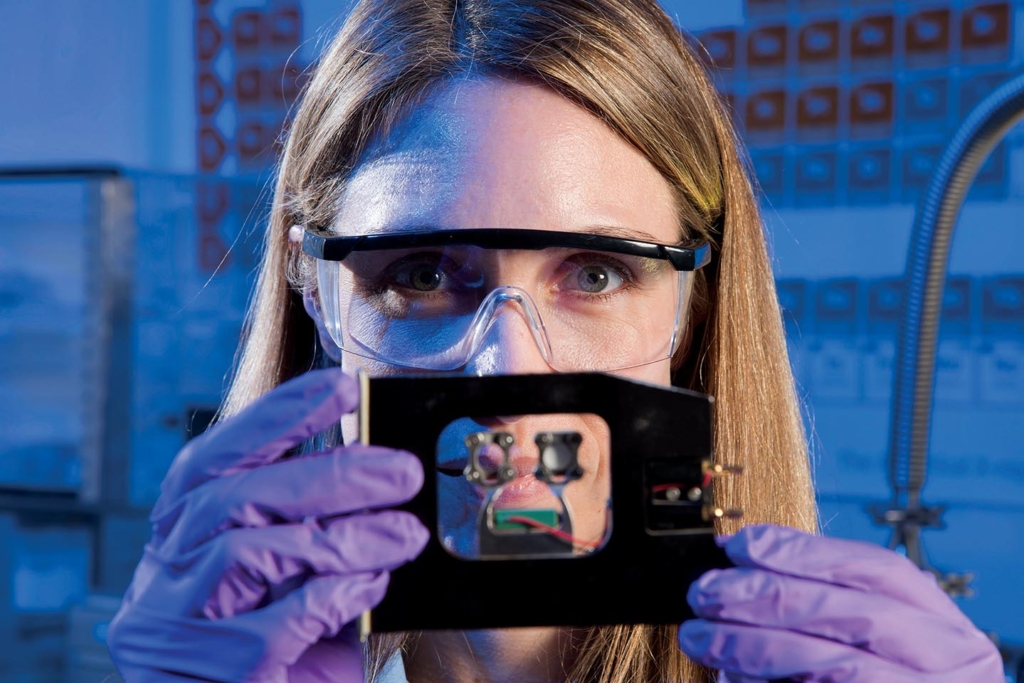

NASA planetary scientist Liz Rampe ’05 studies minerals on Earth that provide insights into Mars.

This summer, Liz Rampe ’05 kept to a schedule. Most mornings, in the shadow of an Icelandic glacier, she scooped sediment at the shores of Sandvatn, an otherworldly lake. For more sample collection, she hiked with colleagues to rivers far from any paved road. But whenever the SUV would pull up to her site, it was time for a break. She’d climb in the vehicle, dig out her bag of supplies, and pump breastmilk. Rampe’s 5-month-old daughter, Wren, was staying with grandparents a one-hour drive away. Mom’s fieldwork would have to wait.

Rampe is a planetary scientist at NASA, and the fieldwork she conducted in that remote corner of Earth has implications for research on Mars. Billions of years ago, Mars may have had rivers and lakes like Earth. It could have looked like Iceland does today. “The big-picture question we’re trying to answer is getting a better idea of what Mars was like three and a half billion years ago, and if it would have been habitable” by microbes or other simple life forms, she says. “We’re studying that through minerals on Earth that are in similar environments to what we think was on Mars.”

The red planet wasn’t always Rampe’s passion. She used to be more of a dinosaur fanatic. “I was always a science-y kid,” she says. Environmental scientist John Rampe ’75 and archaeologist Mary Barger encouraged their daughter’s interests, taking her to see fossil dino footprints a short drive from their Denver, Colo., home. By the time she was ready to follow in her dad’s footsteps at Colgate, she thought she’d set aside childhood interests and major in chemistry. But the Dinosaurs to Darwin course with Professor Connie Soja lured Rampe to geology. In addition, Professor Richard April and senior lecturer Di Keller taught Rampe how to use two specialized X-ray instruments to analyze clay minerals from soils in the Adirondack Mountains. When Rampe began graduate school at Arizona State University, a faculty member noticed her expertise from her Colgate studies. He made an intriguing offer: How would you like to study clay minerals — but from Mars?

“The big-picture question we’re trying to answer is getting a better idea of what Mars was like three and a half billion years ago.”

Liz Rampe ’05

“I knew nothing about Mars,” Rampe remembers, but she said yes and hasn’t looked back. Minerals can reveal a lot about a planet’s past. They’re fossils without bones, records of ancient climate and water conditions rather than a dinosaur’s ancient anatomy. A mineral’s composition can imply that it formed under warm and wet conditions, or cold and icy ones, or at a particularly salty seashore.

While still in grad school, Rampe landed a three-year fellowship to conduct research for a few months out of the year at NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. The center is the famed hub of astronaut training, but it also hosts extensive scientific research. Thus began Rampe’s long-standing relationship with the Johnson Space Center. As of 2017, she is the deputy principal investigator for the Chemistry and Mineralogy instrument on NASA’s Curiosity rover, which has been exploring Mars since 2012. She and her colleagues tell the instrument what to do and analyze its data. The instrument, called CheMin for short, contains miniature versions of the same two instruments Rampe used at Colgate. “It’s just full circle for me,” she says.

Rampe’s fieldwork in Iceland complements the work she does with Mars samples. Curiosity is studying lake samples, so the specimens from Sandvatn might help Rampe’s team better understand how subtle changes in water conditions affect mineral compositions. She and her colleagues conducted additional mineral studies along a river in Iceland to support a different NASA rover, Perseverance, which landed on Mars in 2021.

Rampe is excited to tell her daughter about her job someday. She has a lot of ground to cover. Ultimately, Rampe’s work is about understanding what makes planets good places for life to evolve and asking whether life emerged someplace other than Earth. That’s probably too much for the first lesson, she laughs. “I imagine we’ll start by looking up at the stars.”