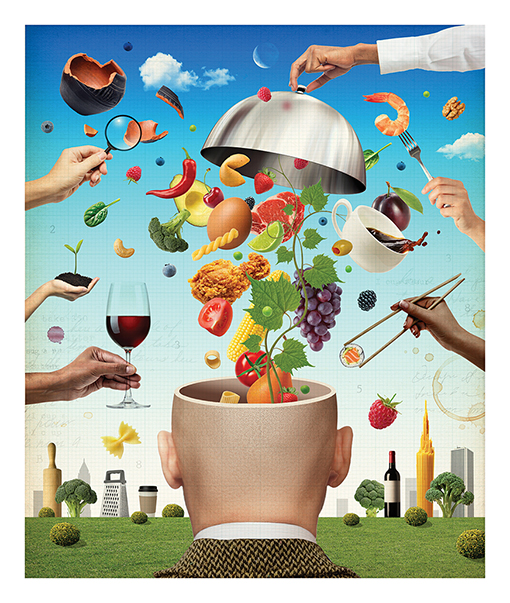

From a morning cup of coffee to an evening glass of wine, from buried pottery to planted seeds, Colgate professors are using food and drink as a lens to explore questions about humanity.

What is Jewish Food?

Jewish cookbooks have changed dramatically over the last hundred years, says Professor Lesleigh Cushing, who is writing her own book about what she’s found in her research. Cushing, who is the Murray W. and Mildred K. Finard Professor in Jewish studies and professor of religion, is a literary scholar.

These cookbooks used to be “steeped in nostalgia,” she explains — immigrants trying to evoke their grandmothers’ kitchens through their matzoh ball recipes, for example. But more recent cookbooks have shifted in focus.

For one thing, Cushing says, the voice of Jewish cookbooks is becoming more masculine, as celebrity chefs like Yotam Ottolenghi pull the cuisine into a less domestic and more prestigious realm. “The food is leaving the home, becoming more chef-like in some ways, but also becoming more global,” Cushing says. Jewish cookbook authors nowadays might even suggest including pork in a dish, or defying kosher law in other ways.

These changes point to ways Jewish identity is changing, too, Cushing says, and to questions about what it means to be authentic (and whether that matters). Are there foods that are Jewish, she asks, or just Jewish cooks who make food? Or neither?

“Something radical has changed about how Jews think about food,” she says, “and how they think about what it is to be Jewish and an eater, a consumer, a giver of food.”

Searching for Soul

Taryn Jordan, assistant professor of women’s studies, is also digging into cookbooks — specifically, soul food. But she’s most interested in the elements of a recipe that can’t be written down. “How does soul food communicate history through taste?” she questions.

One answer lies in fried chicken. It’s “a stereotype,” she says, “but also, the reason the stereotype exists is that enslaved Black folks could keep chickens relatively easily.” After Reconstruction, Jordan says, Black women could help support their families by raising chickens.

Later, fried chicken — a food that keeps well — became important for another reason. “A lot of times when people were traveling, they couldn’t stop just anywhere for lunch because they didn’t know if people were going to be racist or not,” Jordan says. With a cooler of chicken in the car, they could eat without getting off the road.

Growing up, she often heard her parents tell the story of a time when fried chicken in the car may have saved their lives. Her father, traveling with her mother and older siblings before Jordan was born, had pulled off the road for a rest. A police officer knocked on the window. He told the family he had “called some people” when he saw them parked there, and they had better leave town in a hurry. There was no time to stop for food as they fled, but they had chicken in the car.

Whenever she ate what her family called “traveling chicken” — a fried drumstick wrapped in white bread and covered in foil — on road trips, it “reminded me where we came from,” Jordan says. “It allowed me to taste history.”

Jordan’s father was the first Black executive chef in Las Vegas, and Jordan worked as a caterer during grad school. “Food is in my bones,” she says. So she has plenty of firsthand knowledge of the subjects she’s exploring now as a scholar.

As she visits archives and hunts down soul food cookbooks, she’s most interested in the domestic work of Black women in their own homes, Jordan says. She’s hoping to write a book that describes a “genealogy of soul,” looking at not just the food but also the kitchens it’s cooked in and the stories it conveys.

Jordan uncovered one tantalizing story on a visit to the Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library. She was there to see a collection of cookbooks that belonged to singer Ella Fitzgerald. In the collection, Jordan found a cookbook still in draft form: three file folders containing about 150 yellowed pages, some cut and taped together.

It seemed to be an early version of a book called All About Soul: Cooking and Related Subjects by author Aldeen Davis. The manuscript was unusual. The recipes had no measurements, for one thing, Jordan says. “She wanted you to cook with your soul, with your heart, with your feeling.” And the manuscript had odd elements interspersed, such as narrative essays and a key to the meanings of flowers.

It also had a handwritten inscription from Davis, wishing Ella Fitzgerald well. At the end of the note was a startling postscript. “It said, ‘I will never forget last night,’” Jordan remembers. “It made my skin tingle, and I think I teared up a little.”

She doesn’t know what type of relationship the two women had. “This is the mystery of my career,” Jordan says. “And I don’t know if I’ll ever find an answer.” But the love and the shared memory conveyed through the taped-together cookbook perfectly illustrate the themes of her research on soul food, Jordan adds.

“Food becomes a way in which to tell this history through taste and feeling,” she says. “It’s a language that doesn’t have a key; it’s unspoken … it’s only felt.”

“This is the mystery of my career. And I don’t know if I’ll ever find an answer.”

Taryn Jordan, assistant professor of women’s studies

History in a Bottle

In a different archive, Rob Nemes, Charles A. Dana Professor of history, discovered his own puzzle.

He started exploring the National Agricultural Library during a stay in Maryland more than a decade ago. There Nemes found a trove of historical agricultural manuals, books, and pamphlets from around the world, including Eastern Europe, which he studies. Nemes was often the only person in the library, he says. “I discovered this fantastic material in suburban Maryland, opposite IKEA,” he says.

Among the papers, there were numerous manuals from Hungary about wine-growing in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Nemes began to wonder: “What happened to this huge wine industry?” After a trip to the country in 2019, he published a journal article on the history of Hungarian wine.

Although most people haven’t heard of Hungarian wine, the country used to be one of the world’s top five wine producers, Nemes says. But during the late 19th century, an epidemic began to spread across European vineyards. It was a tiny, sap-sucking insect called Phylloxera, imported from North America. The pests ravaged grape vines.

“It’s a little bit like coronavirus,” Nemes says. “They could see it coming, and they had some ideas about how they might stop it, and yet their response was really confused and uncoordinated.”

Half or more of the vineyards in Hungary were wiped out. “A lot of people who had just a few vines were ruined,” he says. Those winegrowers became part of the wave of Eastern European migrants leaving for the United States.

To beat phylloxera, winegrowers began grafting European vines onto the rootstocks of American plants that were naturally resistant to the bug. In one way, it was a triumph of science, Nemes says. On the other hand, “it sort of punished people who stuck to traditional ways.” Much of the local culture around wine-growing in Hungary and elsewhere shriveled up with the blighted vines.

Knowing these histories makes Nemes keenly aware, when he holds a bottle of wine in his hand, that it’s not just something generic, but a product of real people in a certain place. “I’m very interested in the stories and the people behind the bottle of wine we drink,” he says.

The Proof is in the Pots

Some of the stories that food tells aren’t written in cookbooks or on wine labels, but in the walls of pots that have been buried for a thousand years.

Kristin De Lucia, associate professor of anthropology, studies an archaeological site called Xaltocan. The site, near Mexico City, is dry today. But during the period De Lucia is interested in — about 900 to 1250 AD — Xaltocan was an artificial island in the middle of a lake.

Pots and broken pieces of ceramic have taught archaeologists much of what they know about ancient societies like Xaltocan — or, at least, what they think they know.

“Archaeologists tend to make assumptions about what those vessels would have been used for,” De Lucia says. A container with a neck probably held a liquid for pouring, for example. A flat pan probably made tortillas.

To investigate the truth of those assumptions, De Lucia took a closer look. She worked with colleagues at the PaleoResearch Institute in Colorado to analyze microscopic particles called phytoliths from pieces of broken pottery. “Phytoliths are essentially fossilized plant cells. They can become embedded in the little spaces in the walls of ceramics because they’re so small,” De Lucia says. These fossilized cells have distinctive shapes that tell scientists what kind of plant they came from.

The researchers also looked under a microscope at starch molecules from the ceramics to get more hints about what types of plant matter the pots held. Infrared spectroscopy revealed other molecular signatures such as fats from meats. The researchers published their results earlier this year in the Cambridge University Press journal Latin American Antiquity.

Some of what De Lucia found was unsurprising — for example, corn. Its signature in jars suggested Xaltocan residents were making atole, a corn-based drink.

The researchers were surprised, though, by where they didn’t find corn. Two of the fragments they analyzed came from flat pans called comales. Archaeologists tend to assume these were tortilla griddles, which meant they should have held corn starches. “But in fact there was no evidence,” De Lucia says. They did find a possible meat signature, though.

That doesn’t mean comales were never tortilla griddles, De Lucia says. But they likely had other functions, too, like a modern frying pan.

Another type of vessel the scientists analyzed was a large, heavy-duty basin with handles. “I really had no clue what they were using them for,” De Lucia says. But the microscopic analysis turned up many fibers from corn husks. She thinks this is some of the earliest archaeological evidence for people making tamales.

De Lucia and her colleagues also found that different vessels had different purposes. For example, atole with chili peppers seems to have been cooked in different vessels than atole with no peppers. This might have been a way to keep the spice from tainting other meals.

Unlike just counting up the number of jars or pans at a site, this research helps De Lucia imagine the long-ago residents of Xaltocan more clearly, she says. “You can see all these artifacts as things people used.” They boiled or steamed tamales to feed their families; they added spicy pepper to their stew or chose to leave it out. De Lucia says, to her, that makes these ancient people more relatable.

“Cooking, in many ways, defines us,” she says. “It makes us human.”

When a Coffee Mug Is a Window

Rather than pots and pans, Peter Klepeis, professor of geography, is peering into cups and carafes.

He’s teaching a sophomore residential seminar this year called What’s in Your Cup? The Geography of What We Drink. Through the lens of everyday beverages such as coffee, water, wine, and tea, students will learn about the effects of their consumption, as well as how the production of these beverages affects the environment and the lives of the people who make them. Ultimately, Klepeis hopes that both he and his students will learn how to live better in the world.

“Geography is a funky discipline,” says Klepeis, straddling the natural and social sciences. He’s especially interested in relationships between humans and the environment. With this class, he says, he’s “using something we all consume daily to try to make a connection between our consumption and these other impacts.”

After taking the first part of Klepeis’ class this fall, students may be able to see firsthand how some beverages are made. He hopes to take the class to Colombia to meet coffee growers, but the pandemic and social unrest may necessitate a change of plans. Luckily, the themes he wants to explore show up throughout the world.

Klepeis and his students will talk about the working conditions behind certain coffees and other drinks, such as child or slave labor. They’ll also discuss the displacement of indigenous people, forest loss and impacts on biodiversity from farming, and other environmental issues like pollution and waste.

When he taught the class in 2020 as a first-year seminar, students were “surprised by the degree of social and environmental cost to what they’re consuming,” Klepeis says. “They generally don’t think about what they drink.”

It’s not all bad news, though. In Colombia, Klepeis hopes to talk to farmers who are working to lessen their environmental impact and respond to climate change, or creating cooperatives that let them earn better wages.

Klepeis doesn’t think we should feel guilt about everything we eat and drink, but aim to consume mindfully when we have the options and means. (He points out that FoJo Beans in Hamilton sells fairly traded coffee.) Although he personally has been careful about his consumption for a long time, preparing for this class has taught Klepeis new principles and reinforced others — for example, he says, “bottled water is something that we should all be avoiding if we have a better alternative.”

He’s also learned how effective it can be in the classroom to address heavy social and environmental topics through a fresh lens. “You talk about climate change, and [students have] been hearing about this forever,” he says. But when you talk about a hot cup of coffee, he says, “it perks them up.”

From Farm to (Everyone’s) Table

A conversation over coffee several years ago made professors Chris Henke (sociology and environmental studies) and April Baptiste (environmental studies and Africana and Latin American studies) realize they should team up for a research project about how people buy food when money is scarce.

Both professors were interested in whether eating local food might benefit people who experience food insecurity. Are farmers markets and community supported agriculture (CSA) memberships only about pricy peaches and upscale arugula? Or can local food be a practical option for low-income families?

Baptiste and Henke started their project near home. They set up a tent at the Hamilton Food Cupboard and interviewed visitors about their food-buying habits. Students helped develop the survey questions.

They learned that some people were interested in local options such as the farmers market. But, Baptise says, “There definitely were barriers to getting access to local food. The one that stood out to me was transportation access.” It was hard for people to even get to the food cupboard, much less the farmers market. Another barrier was that the Hamilton farmers market didn’t accept SNAP benefits, also called food stamps.

Baptiste and Henke also visited the City of Rochester Public Market, a huge, year-round market that’s different in many ways from the Hamilton market. There, they found better accessibility for low-income consumers, such as vendors accepting

food stamps.

They also spoke to farmers and found that producers themselves oftentimes are low-income consumers. Henke says, “There’s a joke a farmer told me, which I love: How do you become a millionaire in farming? Start out with two million dollars.”

Farming is often economically difficult, and “A lot of the folks we talked to were pretty open about some of those challenges,” he adds. Financial insecurity can also make it harder for farmers to take steps that would make their food more accessible, such as letting consumers pay for their CSA membership in installments, rather than all at once.

In price comparisons, Baptiste and Henke discovered that food from a farmers market or CSA membership is sometimes less expensive than food from big-box stores, depending on the season and other factors. So consumers might find some surprising deals, if they can get past the barriers.

“There definitely were barriers to getting access to local food. The one that stood out to me was transportation access.”

April Baptiste, professor of environmental studies and Africana and Latin American studies

Henke recognizes those barriers himself, as a committed consumer of local food. He says he and his family spend a large part of each weekend driving around town to pick up items like milk and produce. “It’s a ton of coordination to eat that way,” he says. “I realized my locavore privilege from this research.”

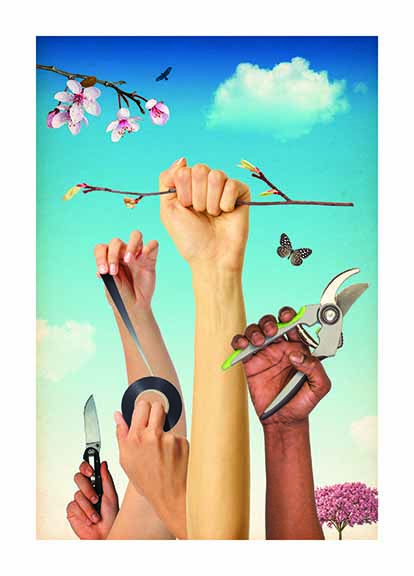

Forbidden Fruit

Assistant Professor of Art and Art History Margaretha Haughwout is also thinking about local food that people can access easily — as easily as reaching out and plucking a plum from a tree.

In her studio in the Village of Hamilton, plants used as food and medicine grow together and support each other. She calls it a food forest studio. (“I have a little bit of an allergy to the term ‘garden,’” she says.) Earlier this year, she used plants from that studio to build a permanent installation called Food Forest Futures at Bennington College.

The installation started with a group of five hawthorn trees Haughwout found growing at the boundary between a mown lawn and a wilder wooded area. Around those trees, she planted two disease-resistant chestnut trees, along with other plants, including cherry trees, grape vines, peas, elderberries, and herbs. The plants are meant to help each other grow while providing food for people and other creatures.

Her goal, Haughwout says, is “to inspire a radical imagination about what’s possible in our spaces.” What if a plot of land for growing food could also be a wild, natural place that didn’t need as much human intervention? What if apples and pears grew on city streets?

Toward that end, she works with a group called the Guerrilla Grafters, which first sprang up about a decade ago in the Bay Area. Guerrilla Grafters find the sterile fruit trees planted along city sidewalks, such as ornamental pear, cherry, and plum. Then, during a brief window in the spring, they use a knife to slice branches from the ornamental trees and attach branches from actual fruiting varieties. The grafters work stealthily, since the act may be unwelcome or illegal.

These branches often bloom in different colors than their host trees, Haughwout says, though they may not bear fruit for several years.

Haughwout started working with the Guerrilla Grafters when she lived in the San Francisco area and now works with groups in New York City. When I’m walking in the city, I’m constantly observing where the fruit trees are,” she says. She also hosts an annual exchange where grafters come together and swap branches to bring back to their neighborhoods.

“We hear from people all over the world who are doing this practice,” she says.

If she encounters neighbors while she’s grafting a tree, Haughwout says, she’ll talk to them about what she’s doing. But in other cases, her creation may go totally unnoticed at first. That’s OK, she says, because the kind of art she’s interested in making isn’t only visible. Rather, she’s interested in

art that inspires people to act or to change their perspective.

Sometimes there’s conflict between the grafters and city officials, for instance. “I tend to think if the government gets alarmed, then I’m on the right track,” Haughwout says. “As an artist, I have some ability to be antagonistic in a playful way.”

If people read about these conflicts and start to think about different ways public spaces could be used, or if they visit her food forest installation and feel inspired to plant a seed in their own communities, that’s her real work, Haughwout says. “It’s not just the branch. It’s these larger conversations and actions that emerge.”