Photos by Mark DiOrio. (Editor’s note: Photos were taken on March 17, before the governor of New York State recommended wearing face masks.)

Colgate’s emergency response system was forged in fire, but don’t let the dramatic origin story fool you. When crises arise, the University still follows a simple rule: remain calm and activate the EOC.

Andrews Hall residents report that their roommate never returned home after stepping out for a late-night slice. A tornado has ravaged campus. A student-athlete has been medevaced to Utica with symptoms of meningitis. An epidemic has become a pandemic, and the governor has just closed all state-run institutions of higher education.

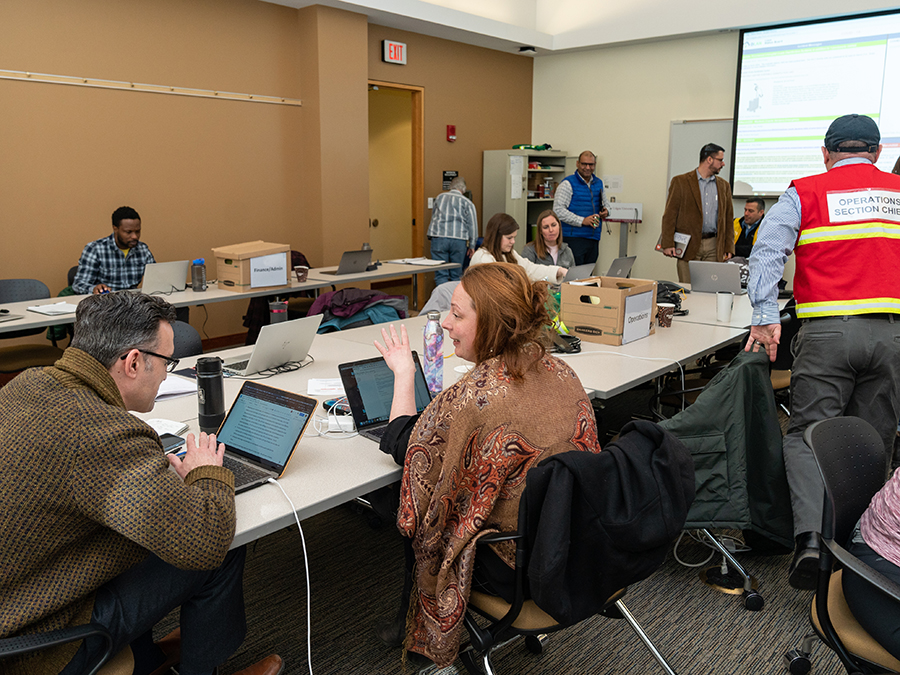

For members of Colgate’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC), these might be monthly training scenarios or the real thing. Either way, it all starts with pings on cell phones. If you work on a floor with multiple EOC members, you hear the alert tones roll from office to office, first a text and then an email. Brief lines announce an EOC activation and describe the nature of the emergency. More than 50 people assigned to this response team will begin a double-time walk across campus to the designated meeting location, where DLAN — a web-based situational awareness software program — is already projecting incident details onto a large screen. Laptops come out.

There is a particular kind of silence in an initial EOC activation. A room full of people normally hums with conversation, but in these moments, everyone is trying to take in as much information as possible, as quickly as possible. They are mastering their emotions — the words and pictures must be the stuff of bad dreams or their presence wouldn’t be needed. Any conversation is typically at a librarian’s whisper, not by mandate, but because that’s how a body wants to speak when dozens of people, packed together, are so completely wrapped up in concentration.

“Attention in the EOC.” The call comes from the incident commander, standing at the front of the room. Attention couldn’t be higher, but the volume and authority of the statement pull staffers out of their thoughts and into the moment for a full briefing. These four words mark the beginning of what could be a long, challenging period for staff as they guide the University community through trauma and disruption.

Define the Scope

In autumn 1970, Southern California was burning. Between Sept. 22 and Oct. 4 of that year, while Colgate students debated women’s rights and administrators fretted over dwindling financial aid resources, fires scorched 500,000 acres — nearly 800 square miles — on the other coast. Seven hundred buildings were destroyed and 16 people died. Fire districts shared personnel and equipment in the attempt to prevent flames from leaping canyon to canyon, forest to forest. State and federal agencies poured resources into fighting the blazes, too, and when the smoke cleared that winter, the after-action reports noted no problems with the firefighters, their gear, or their tactics. But experts agreed that, if multiple districts and counties, the state, and the federal government were going to win the battle against California’s large-scale natural disasters in the future, they needed to make significant operational changes. In particular, they had to speak a common language on the same radio frequencies, share their resources, and make decisions based on the same information.

Five years later, an interagency partnership introduced Firefighting Resources of Southern California Organized for Potential Emergencies (FIRESCOPE). It included an Incident Command System (ICS) that promoted collaboration and clarity of purpose on the ground and a Multi-Agency Coordination System to handle cross-jurisdictional interactions as necessary. At the heart of the ICS sat the EOC, headed by a single incident commander, typically the senior officer on the scene, overseeing four sections: planning, suppression and rescue, logistics, and finance. FIRESCOPE, in spite of its title, was adaptable to non-fire emergencies, scalable for use by single districts, and resilient, given the constant upgrades to technology, forecasting software, and other tools of the trade. Developers and adherents were proud of their system and honed it for decades, but among first responders, it was always known as a firefighter’s protocol.

Then came 9/11. A lot of communication took place that morning. In the lobby of New York City’s 1 World Trade Center, firefighters at their command post were on their radios, calling out locations of victims trapped in the burning high-rise. Dispatchers received offers of help and routed engines from other locations to the scene of horror. There were ambulances, police, federal law enforcement, volunteers, and self-activated retirees all converging on the same location for the same purpose. The problems foreseen by California fire officials decades earlier became reality:

Throughout the response on September 11, the FDNY and NYPD rarely coordinated command and control functions and rarely exchanged information related to command and control … We believe there were very limited communications, either directly or through a liaison, between senior FDNY chief officers and the senior officers in charge of the NYPD response. In addition, some potentially important information on the structural integrity of the buildings never reached the Incident Commander or the senior FDNY chiefs in the lobbies. — New York City’s report, “FDNY Fire Operations Response on September 11”

In the aftermath of 9/11, the newly formed Department of Homeland Security (DHS) sought a single system that would, again, allow everyone to speak a single language and draw on shared sources of information. Thanks to the work that had been done more than three decades earlier, they didn’t have far to look. DHS and its partner departments took the proven FIRESCOPE system, modified it slightly, and called it the National Incident Management System (NIMS)/Incident Command Structure (ICS). No longer just a firefighter’s system, it became the mandatory emergency operations approach for any federal, state, or local agency receiving funding and material support from the U.S. government.

The heart of the structure, still known as the EOC, remained almost unchanged. The NIMS EOC comprises five sections: operations, logistics, planning, finance and administration, and the executive group. Section chiefs guide the work of logistics, planning, and finance, reporting to the incident commander, who oversees the operations section and sets mission objectives. A liaison on the incident commander’s staff communicates between the EOC and the executive group, which typically includes elected officials and policy makers. A communications officer also serves on the command staff. Because NIMS is now a national standard, this structure can be found responding to a house fire in Peoria, an earthquake in San Bernardino, or a bombing in Boston. It is designed to be efficient and scalable; sections can be reduced or disbanded depending on the nature of the situation.

Scale to Fit

The NIMS/ICS EOC arrived at Colgate in the backpack of Dan Gough, the new director of environmental health and safety (EHS), in 2010. A Brown University graduate, Gough learned the system during his 11 years in the Navy, putting to sea on a fast attack submarine, supply ship, and guided missile destroyer. His billets included navigator, weapons officer, combat systems officer, and force protection/anti-terrorism officer. He practiced deploying ICS in the higher education context at Rhode Island’s Roger Williams University, where he was EHS director for half a decade. The endurance required to see it through — that came from the years in between, when he was a professional marathon runner, sponsored by Nike.

Until Gough’s arrival, Colgate, like most universities, had a stack of plans for incidents ranging from toxic chemical releases to public safety threats. Gough characterizes it as “an ad hoc approach, addressing each incident as its own little universe.” But the EOC structure offered a solution that would apply to any and all emergencies in a uniform fashion. It could be practiced in periods between deployment. It could even be used to counter unforeseen contingencies, because, no matter what, the structure and the associated duties would remain the same.

Gough set out to preach the EOC gospel, but implementing the system wasn’t easy. “We’ve blended it to fit the University and catered it to higher ed, because it gets weedy with resource assets and additional command staff acronyms and names, and that just wasn’t going to work,” Gough says. “That would have really pushed people further away. It took a good three years for people to understand it and appreciate its efficiency.”

Then there was the expense. Even back in the mid-’70s, FIRESCOPE called for communications equipment and situational awareness software to track activities, weather forecasts, and more. The University dedicated resources to purchase DLAN, a software package that allows EOC staff and the executive group to share all of this information in real time. The EOC would need places to meet, both on and off campus. (In the case of an active shooter, it would be unwise for the University’s response team to meet and move between buildings on the Hill, so Gough and colleagues identified an alternate site in the Village of Hamilton.) Both of these locations needed to be outfitted with communications equipment, screens, radios, chargers, and other necessities.

If, after navigating Colgate through a series of emergencies both large and lesser, the EOC needed a proof of concept, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided it.

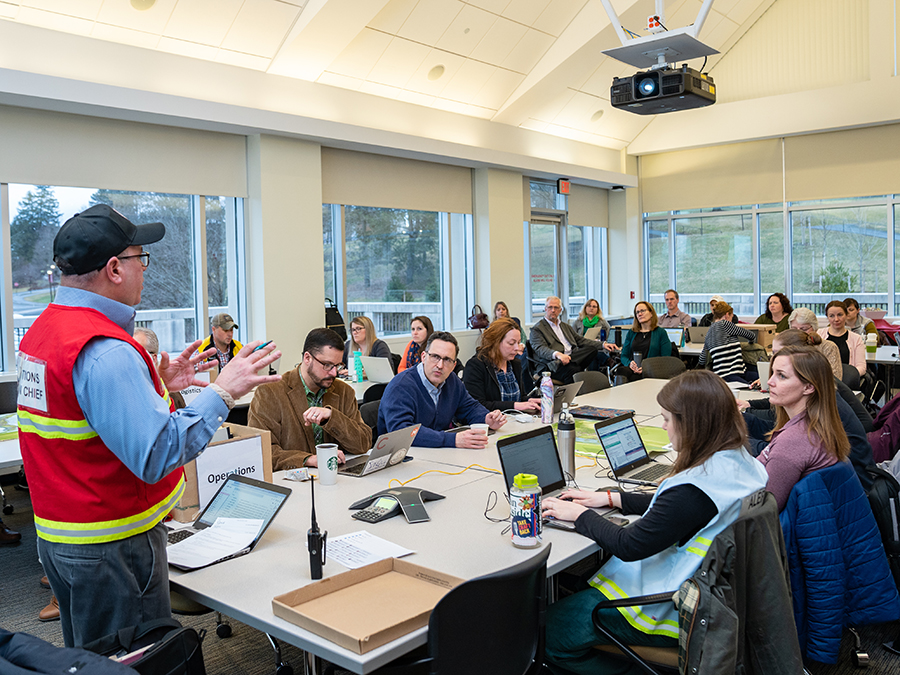

Effective EOCs also demand people power. Gough envisioned a robust EOC, following as closely as possible to the letter of the NIMS/ICS program, so he needed each division within the University to dedicate significant staffing to the effort, train them, and allow them time for monthly drills. In the event of a true emergency, these individuals would be expected to leave their normal work behind and head to the EOC gathering point. Their traditional lines of supervision, and, in some cases, the kinds of jobs they were originally hired to do, would be left at the door. EOC members serve their section and report to the section chief.

“People will say that they operate in this ICS structure, and they will show you six or eight people, including the president, around a table in a small conference room,” Gough says. “That’s not the ICS structure.”

Get Comfortable Being Uncomfortable

By the time Gough left Colgate in 2016 to become environmental health and safety director at the University of California–San Diego, the EOC was well established at Colgate. He returned to Hamilton, N.Y., as the University’s associate vice president for campus safety, emergency management, and environmental health and safety a year later, resuming his position as the go-to incident commander. Today, the EOC is activated not only for emergencies but also to manage large-scale events, from homecoming to commencement.

The EOC comprises five sections:

• Operations • Planning • Logistics

• Finance and Administration • Executive Group

The team meets monthly under normal circumstances. After signing in, members report to their sections. Every other meeting is a tabletop exercise devised by EHS staff members. The incident commander begins with a briefing on the basics of the scenario. Pressure builds on staff as new facts come to light. Will classes be canceled as a result of the emergency? Talk to the planning section, which has the full list of courses and associated faculty members. Will a shelter need to be set up in Sanford Field House? Talk to logistics for work orders to set up beds and generators, and make sure that the operations section is aware so they can coordinate communications and deployment of health services staff. The finance section will set up a budget code and clear purchases. Sixty minutes disappear.

Gough will subsequently use the decisions and advice compiled in the general EOC drill to fuel the same exercise with members of Colgate’s executive group, which includes the president and his cabinet.

“It takes many skilled colleagues, responding in a rapid and detailed fashion, to proceed forward during a major problem, and the EOC structure allows us to gather and succeed,” says Dr. Merrill Miller, director of student health services and a mainstay of the operations section.

If, after navigating Colgate through a series of emergencies both large and lesser, the EOC needed a proof of concept, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided it. Colgate’s EOC was first activated on Jan. 23 in response to the pandemic. Since the week of March 10, it has been under a sustained activation. Daily gatherings began in person and then shifted to biweekly Zoom meetings when the campus transitioned to remote work. The tables that once hosted EOC sections are now virtual breakout rooms. Working within sections, staff and faculty members have provided expert advice to guide executive-group decisions. Then, they have done the work required to implement those decisions, which included the deployment of hundreds of online courses, the depopulation of campus, the safe return of hundreds of students from programs abroad, as well as housing and feeding a small number of students who were unable to return home. With the initial crisis addressed and remote learning in effect, the group turned its focus to the future. A running spreadsheet shared between the EOC’s five sections at one point logged more than 80 of the countless decisions that needed to be made between April and September — everything from the approach to be used for training 2020–21 Link staff to whether the University would offer its July 4 fireworks display.

The EOC is charged with briefing and interfacing with the President’s Task Force on Remote Learning and the Task Force on Reopening the Campus to support their efforts as well. As you plan to return to in-person learning during a pandemic, you will need to know exactly how the University will sustain its commitment to community health and well-being: how many test kits can be stocked per week, how many disposable gowns are available for research labs and student health services, where temperature checks can be conducted, where custodians have conducted deep cleaning, how employees will log their health status, and how many students can safely fit into a classroom that used to accommodate 50.

Conforming to the intentions of its long-retired designers, the EOC structure has ordered and focused the University’s considerable institutional knowledge and individual wisdom. Thanks to its careful design and national standardization, the EOC has provided the common language and procedures that smooth the flow of information between the University and health policy partners at the county, state, and federal levels. It has furthered Colgate’s hard-earned reputation for knowing what it’s doing.

“Whether we are dealing with the challenges of a serious infectious disease or other threats, the EOC and our community colleagues have worked together,” Miller says. “We have all benefited from the EOC’s thorough and wise guidance.”