By Robert Garland, based on his new book from Pen & Sword Books

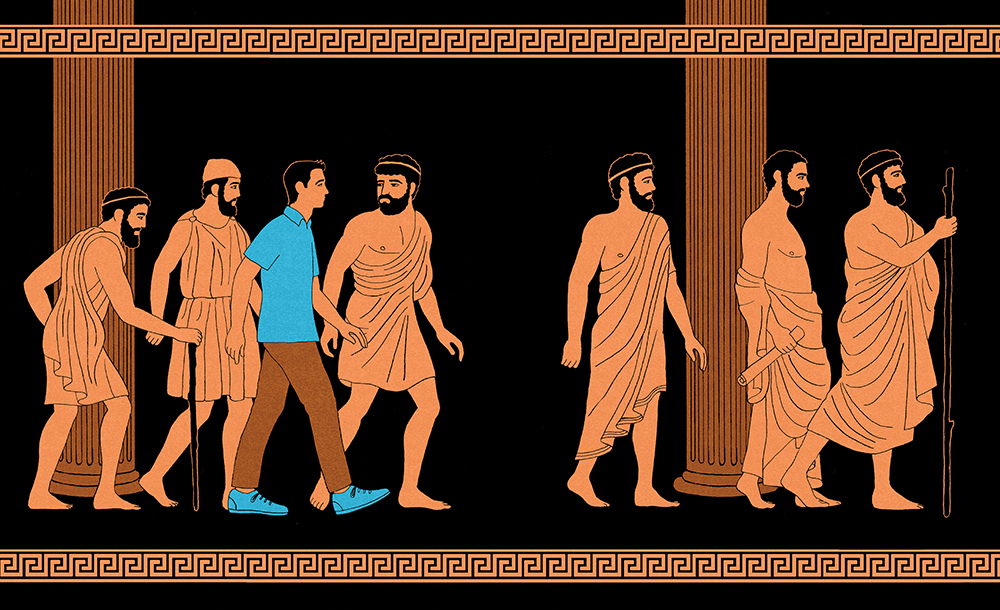

Imagine you suddenly find yourself transported back in time, to late 5th-century Athens. What do you need to know in order to survive?

The year is 420 BCE, when Athens and Sparta are enjoying an uneasy peace. Athens’ manpower is revitalizing after a devastating plague; she rules a maritime empire that dominates the eastern Mediterranean; she has invested more faith in the judgment of the common man than any society before or since; Sophocles and Euripides are writing tragedies that will provoke audiences 2,400 years later; medical science is advancing; and the Parthenon, the greatest Greek temple ever built, crowns the Acropolis.

In short, human excellence has reached a peak. You might not want to stay too long, however, for five years later, Athens will make a decision that will set her on a downward spiral, ultimately leading to her total defeat at the hands of Sparta and her allies.

What you should know about classical Athens

Most of our evidence about classical Greece comes from Athens, the city named after the goddess Athena. That’s because the Athenians are both highly literate and accomplished in all branches of artistic expression. This helps us to envisage how they lived in some detail.

Athens’ surrounding landmass, known as Attica, is shaped like an elongated carrot and comprises some 1,000 square miles. Its urban center is more like a medium-sized provincial town than a metropolis in our understanding of the word.

The total population of Attica is about 150,000, half of whom live in Athens and the other half in the countryside. Approximately half of the population, too, are slaves and will remain so all their lives.

Having produced more men of genius per capita than any other place in history, classical Athens is remarkable by any standards. Its contribution to western civilization — in literature, art, history, architecture, philosophy, and many branches of science, including astronomy and medicine — is unparalleled.

What your house looks like

There aren’t two distinct words for “home” and “house” in Greek. Oikos and oikia both mean “house” and “home.”

Most houses are flat-roofed dwellings made of mudbrick with a tiled roof. The mudbrick is often covered in plaster. In the center of the main room, there’s a hearth. There’s no chimney; just a hole in the roof, by which the smoke, or at least some of it, escapes. Windows don’t have glass panes; only shutters. This means that in cold weather, when the shutters are drawn across the windows, it’s dark and smoky. The only source of artificial lighting is small lamps that burn animal fat. If you’re well-to-do, you sleep in a wooden bed. If you’re not, you sleep on the floor, which is beaten earth with perhaps matting or straw on top.

In the courtyard there’s a small altar where you perform daily sacrifices to your household deities. There are one or more flimsy structures to accommodate your slaves, though your domestics sleep in the house.

The boundaries of your property are marked by heaps of stones. In some cases, these will take the form of herms: pillars mounted with the head of Hermes, god of boundaries and commerce. The pillars are uncarved except for an erect penis. This is intended to be apotropaic — to deter would-be malefactors and trespassers.

How women have to behave

If you’re a “respectable” woman, you’re expected to spend most of your time inside the home. It’s your task to manage the running of the household, including the education of your children. Convention demands that you never leave your home unaccompanied.

The statesman Pericles once said, “A woman’s greatest glory is to be talked about neither in praise nor in blame.” In other words, you’re expected to be socially invisible.

Modesty is also important. When you do go outside, be careful not to expose any part of your face or body. I suggest you drape your cloak over your head to cover your face. Likely, your husband will be out of the house most of the day, either working, engaged in public business, or merely chewing the cud in the Agora (town center). He regards this as his male prerogative.

Most of the time, you’ll be reliant on your relatives (female, of course), your slaves (also female), and your children for companionship. You probably can’t read, though if you’re wealthy, your husband might purchase an educated slave who can read for you.

Whichever social class you belong to, you’ll be expected to contribute to the welfare and prosperity of the home. One of the chief ways you can do this is by spinning and weaving. Even Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, owns a distaff (hers is made out of gold), with which she spins wool or flax into yarn or thread. Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, deceives her suitors by pretending to weave a shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes, and then undoing the weaving at night. She’s told them that she will marry one of them only after she’s finished weaving the shroud. She held them off for years by this ruse.

What it’s like being elderly

Being elderly is a mixed bag at best. You’ll feel a lot of aches and pains. Both your sight and hearing will be impaired. Almost inevitably you’ll be leaning on a stick or hobbling on a crutch. You’ll probably begin demonstrating the symptoms of old age by the time you’re in your 40s or even earlier, assuming you survive that long. (In Athens, about half of the population is dead by the age of 40.) The medical profession doesn’t concern itself with the elderly.

That said, as a senior citizen, you’ll be looked up to and treated with respect. That would be especially true if you lived in Sparta. The Spartans are famous for deferring to their elders. They stand aside for them in the street.

Though there’s no old-age pension, you can support yourself by jury service, which pays a drachma a day, though the work isn’t guaranteed, and it’s only an option if you live in Athens or close by. Maybe you’ll be able to continue working on the land, like Laertes, Odysseus’ elderly father, who tends vines.

Homer describes a happy old age as “glistening” or “shiny.” What he means by that is unclear, but it does at least suggest that longevity isn’t without its compensations, so long as you are well-heeled.

What you eat

The Greeks eat only two meals a day: a fairly light meal early on called ariston, which consists of olives, cheese, honey, bread, and fruit, washed down with diluted wine; and deipnon, a heavier meal in the early evening, also washed down with diluted wine. (Wine is more trustworthy than water.) If you get peckish mid-morning, you can always grab the equivalent of a souvlaki, i.e., bits of vegetables and scraps of meat on a skewer. Wealthy people eat fish or meat for their deipnon. If you are poor, sausages are readily available. The downside is that they tend to be stringy and the meat is pretty dodgy. Casseroles and stews mostly comprise beans and vegetables. There’s no chocolate or sugar. Oranges, lemons, tomatoes, potatoes, and rice haven’t been discovered either. Salt is available but not pepper, and there are no spices.

It’s going to be a challenge to get used to the cuisine. At best, it’s going to taste rather bland. At worst, it’ll turn your stomach.

The good news is that you won’t have to count your daily calorific intake. You’ll be able to consume as many calories as you can get. You’re almost certain to come up seriously short compared with what you normally eat. For that reason, you won’t see many obese people in ancient Greece.

Ways of travel

Many Greeks walk long distances on a regular basis, whether for recreation or for work. At the beginning of Plato’s Republic, Socrates has walked 5 miles from Athens to the Piraeus to witness a festival, and he would have returned to Athens the same day, had he not been spotted by a friend, who urged him to come back to his house. In the countryside, it’s a common sight to see men and women riding on a donkey. Horses are pretty useless over any distance due to the roughness of the terrain. For the same reason, chariots are unsuitable as a method of transport. The mountainous nature of the landscape is partly why the system of independent city-states has grown up, since it’s generally difficult to get from one polis (city-state) to another.

If you want to get anywhere quickly, I suggest you run. The chances are, your feet are calloused and have been since you were a child, so you’ll hardly be conscious of the rocks and the brambles you’ll encounter along the way. Of course, that’s only an option if you’re a man. A woman can hardly hitch up her dress and expose her knees, except under dire emergency.

The political arena

Participation in politics is expected of every adult male Athenian (women aren’t considered citizens). In the speech that he delivered in honor of the soldiers who died in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, Pericles remarked, “We regard the man who takes no part in politics not as somebody who minds his own business but as good for nothing.”

You are expected to attend the assembly and vote on every issue under debate. Meetings take place four times a month. Though the agenda is decided by the council of 500, any citizen is entitled to bring forward a subject for discussion.

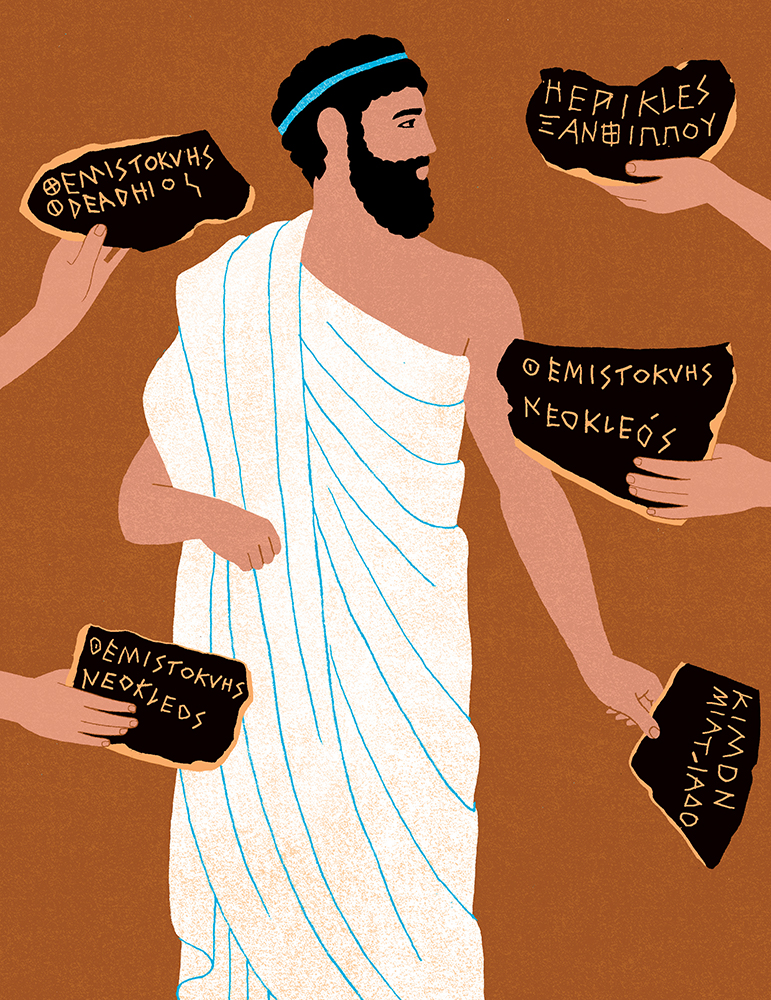

Once a year, the Dêmos (the people) are asked if they want to hold an ostrakismos, or ostracism. If they vote in the affirmative, every citizen will subsequently write the name of the prominent individual whom he wants to send into exile for 10 years. The citizens write on an ostrakon — a piece of broken pottery, which is the most readily available writing material. This is the origin of our word “ostracism”; literally “a vote that is recorded on a potsherd.” This expedient is evoked when two politicians are constantly locking horns and producing a stalemate. An ostracism breaks this impasse by eliminating one of them from the political arena. It isn’t a punishment as such, but a kind of negative popularity contest.

How to get the gods on your side

There are two ways to invoke the favor of a deity: by making a votive dedication or by performing a sacrifice or libation. Such actions must be accompanied by prayer. Where appropriate, remind the deity of any previous gifts you have given or sacrifices you have performed. That will help grab their attention. Always remember that they’ve got better things to do than attend to the gripes of wretched mortals.

A votive dedication is anything of value. For instance, it can take the form of a small terracotta figurine in the image of the deity, which you deposit in the sanctuary or inside the temple. But, it’s best if you give something precious; a bronze figurine, say, or, better still, a life-size statue. If you’re an aristocrat, you might commission a hymn and have it sung by a choir.

A sacrificial victim might be a sheep, goat, or pig. The more victims, the merrier. If worse comes to worst, offer a chicken or some produce from your garden. As a libation, make an offering of wine, honey, or milk; or all three combined. The same principle obtains with sacrifices and libations as it does with dedications: The more generous you are, the more likely the deity will heed your prayer.

The worship of the gods is conducted out in the open. No religious observance takes place inside a temple, which is used solely for displaying the cult statue and storing dedications and implements that are used for cultic purposes.

Why you might want to consult an oracle

The Greeks believe that their gods regularly send signs intended to warn them of the outcome of their actions, so it’s a good idea to consult an oracle whenever you’re faced with a big decision.

The most important oracular sanctuary is that of Apollo at Delphi. Be prepared to wait in line. Apollo’s sanctuary is only in session for a few days every year, and there’s bound to be a long queue of petitioners.

You will put your question to the god through a priestess who is called the Pythia. She’s so named because Apollo’s cult title is Pythios. The god was given this title because he killed a python when he first arrived at Delphi. The Pythia, a female medium, will give you Apollo’s response. Quite likely, what she utters will be unfathomable, in which case an interpreter will promptly step forward and, no doubt for a fee, explain its meaning in plain Greek. Even then you will need to study it carefully and not jump to rash conclusions. The words “know yourself” are inscribed on the retaining wall of the sanctuary. Knowledge of the future is not much use without self-knowledge.

Professional seers equipped with prophecies are also plentiful throughout the Greek world, so if you can’t make it to Delphi, you can engage the services of a seer in Athens.

Meteorological phenomena such as eclipses and flights of birds are other tried and tested methods of gaining insight into the future. You’ll soon learn that the gods are doing their best to assist you in your decision making. You’ll have no one but yourself to blame if you don’t take their warnings seriously.

A final word of advice

There’s no doubt that adjusting to ancient Greece is going to be something of a challenge. Life, as you have gathered, is lived without amenities, labor-saving devices, and the many distractions that enable us to escape the harshness of reality in the 21st century.

You’ll be almost wholly dependent on your friends for entertainment, other than the rare times in the year when dramatic performances occur. I recommend that you put a high premium on conversation.

You’re going to be living much closer to the edge in all kinds of ways. Your vulnerability to accident, disease, famine, fire, and war is reflected in the fickleness, jealousy, and vengefulness of your gods.

I hope I haven’t put you off too much. There are also many compensations to justify your moving to classical Athens. Your oikos (family) will be a much closer-knit structure than families are generally today. You’ll feel a stronger degree of kinship to a much larger community than most people do today. Your polis will be more unified than virtually any modern society. All the members of the polis, slaves included, are facing certain inescapable existential imperatives. Of these, the principal imperative is life’s unpredictability. In other words, everyone is in the same boat.

Unless you happen to be standing beside an odiferous pile of dung, you’ll find the air is pure to a degree that you may never have experienced before. From the Acropolis on a good day, you will be able to see all the way to Acrocorinth in the Peloponnese, some 60 miles distant. At night, the stars will be more plentiful and brighter than they are almost anywhere in the developed world today. Also, there won’t be any chemicals in your food.

Racism is largely unknown. You’re unlikely to encounter any color prejudice. You may even discover that the Greeks are darker-skinned than you will be expecting.

Greek women are generally subject to male authority, but don’t assume that if you return to ancient Greece as a woman you will automatically be complaining about your lot in life. You might see certain advantages in being looked after, even at the cost of your personal liberty. There are many hazards and threats out there.

Don’t take your 21st-century sensibility with you. You’re not going to encounter anyone advocating women’s liberation or debating the ethics of slavery. You’ll have to accept that slavery is a fact of life.

Your sense of hearing will be much more acute. You’ll be able to pick up sounds from a far greater distance. Your sense of smell will be more intense as well. That’s because you’ll be more reliant on these senses for your safety than you are today. In the absence of spreadsheets, filing cabinets, and the like, your memory will be vastly superior. You’ll be able to remember long passages of literature, deliver lengthy speeches, and reel off information effortlessly. Everything will be safely stored in that complex computer we call the brain.

If you have an ounce of sensibility, the beauty of the natural world, uncontaminated by the human species, will knock your nonexistent socks off.

Greek poets are always writing about the misery of human existence and wishing they were dead. “Not to be born in the first place is best for men on earth, or if born to pass through the gates of Hades as quickly as possible,” writes gloomy old Sophocles. But is that the majority view? I seriously doubt it. Most Greeks, I suspect, relish life to the full, and it is for that reason above all that I would love to return to ancient Greece and why I recommend you do too.

Robert Garland was the featured guest on Colgate University’s podcast, 13, on April 6. Listen to the episode as he discusses the plagues and pandemics of the ancient world and more.

Garland’s Odyssey

Over the past 34 years, Professor Robert Garland has been a time-traveling tour guide, taking students and audiences back to ancient Greece. In light of the classics professor’s retirement from Colgate, we guide you through his time in Hamilton, starting with his arrival in 1986.

An epic blizzard was pummeling central New York when Garland traveled to campus for his interview. He’d been invited by then chair of the classics department, John Rexine. In addition to Rexine, Garland was to interview with Jerry Balmuth, but the philosophy and religion professor never showed because he couldn’t get out of his driveway. The weather continued to threaten Garland’s positive impressions of central New York during his snowy departure in a taxi to the airport. “I’m not a praying person, but I said, ‘God, if you get me back, I promise I’ll be good,’” remembers Garland, who had spent most of his life in England. Rexine must have also had the gods on his side, because he convinced Garland to return to Colgate.

“The classics is a passionate subject,” Garland says in explanation for his fervor for the discipline. “The Greeks were always banging on about how life is brief and carpe diem.” The subject matter is full of humanity, he adds, offering The Iliad’s ending as an example. “Priam enters the tent and kisses Achilles’ hands that have slain so many of his sons, and the two weep together. They’re no longer Trojan and Greek, they’re just two human beings. That is the essence of what I want people to know: We’re all the same.”

These lessons, Garland hoped, were ones his students would keep pondering outside the classroom. “I liked to say to them, ‘Do you go off, as I did, and talk with your best mates about the nature of human existence?’”

When he was outside the classroom, Garland explored creative ways to share his subject matter. Some of the highlights of his career, he says, included directing a standing-room-only production of Lysistrata at The Palace Theater, as well as Prometheus and Antigone.

The theater has long been an interest of Garland’s, having trained as an actor at London’s Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts in his 20s. “I’ve always had that other side to myself,” he says. “I think it made me a more effective teacher because I was conscious of my audience.”

Garland has also invited audiences into ancient history with his numerous books — although How to Survive in Ancient Greece is a departure from his usual academic writing. “I wanted to break out of the straitjacket,” he says. “I looked at this world, and I tried to suggest that it is one worth visiting. I chose a moment in Athenian history when there was optimism. And I treated it as an exercise in imaginative engagement.”

In the book, he flexes his creative muscles in other ways, too: Several of his illustrations bring the text to life. Garland committed to a regular drawing practice over the last two years, working primarily in charcoal and crayon. “I particularly like two tone — black and terracotta — because those are very Greek, as seen in their vases,” he says.

In retirement, Garland plans to continue with his art, as well as occasionally teach online through the Great Courses.

Just as he was preparing to leave Hamilton for his new home in New York City, a snow storm loomed. But, history proved that Garland can handle it; now he’s ready for the future.

— Aleta Mayne