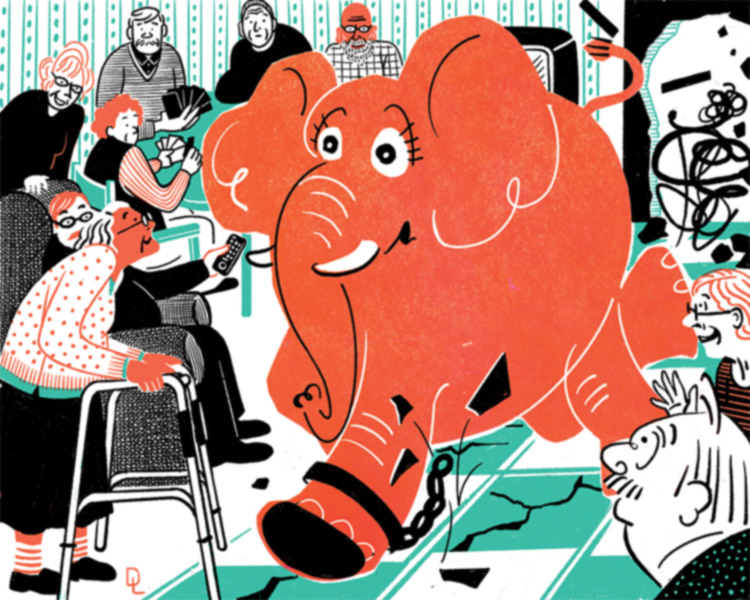

What happens when a pachyderm named Barbara is on the loose

Editor’s Note: Both of these essays are excerpted from a new book by Steve Hannah ’70. Dairylandia: Dispatches From a State of Mind (The University of Wisconsin Press) is his “love letter to middle America.” Hannah is a former managing editor of the Milwaukee Journal and was a longtime CEO of The Onion. “The Elephant in the Room” is reprinted with permission from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “The Ordinary Life,” the book’s postscript, is reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved.

One Sunday morning in August 1977 — a few years into my stint with the Milwaukee Journal — I got lucky. I was living out in the country and driving into metropolitan Sauk City to play tennis. As I passed through the adjacent village of Prairie du Sac, I saw what I took for a hallucination: A very large elephant was cruising up the street in front of me. It pounded down the sidewalk, tore across somebody’s front lawn, then turned up the driveway and into the backyard. I had a hyperactive imagination in those days. So I instantly thought of a scene from Ernest Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa, only instead of great white hunters tracking a rhino on safari in Tanzania, these were brave Wisconsin boys standing on the bedliner of a Ford pickup chasing a circus elephant a stone’s throw from my favorite tavern on Water Street.

It was an unusual sight. I had never come across an elephant on the loose in Prairie du Sac before — or, for that matter, since. So I joined the chase.

In his most profiteering moment, P.T. Barnum could not have concocted a more astonishing publicity stunt. But this, ladies and gentlemen and children of all ages, was no hoax.

Here is what happened just before midday, a dull and dreary summer afternoon in the little but lyrical village of Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, when the Carson & Barnes Traveling Circus came to town.

The circus hands, helped by the biggest and strongest of their 31 elephants, were hauling up the big top. According to Ted Bowman, the business manager of this traveling road show, the elephants were fully harnessed and in the process of hoisting the poles that support the tent.

Barbara, the very same four-ton pachyderm who made headlines when she bolted from the circus grounds in Fond du Lac a few weeks back, was part of the rigging crew. “She was pulling a pole up but when she almost had it upright, it slid off a bump in the earth and went clattering to the ground with a great commotion,” explained Bowman. “The noise must have scared her and, well, she just took off.”

“Took off ” is a bit of an understatement. For the next two hours, Barbara, all of 36 years of age and hobbled by chains connecting her front legs, led the circus animal keepers, local and county cops, the Prairie du Sac and Sauk City Volunteer Fire Departments, and a legion of joyriders on a 4-mile jaunt around town.

Sauk-Prairie police sergeant Paul Harman, doing his best imitation of a cop acting like elephants run through here regularly, said: “The elephant first went two blocks east to Water Street and then reversed direction. She went up past the ballpark, past the hospital, and made a beeline straight for the Maplewood Nursing Home on Sycamore Street.”

Judy Carr, 24, who is married to the circus elephant trainer, said Barbara never was one to let a mere building deter her. “When she got to the nursing home, she looked into a glass window, saw her reflection, and charged. She busted the glass, stopped, turned to her right and saw another, bigger window, and went straight for that one.”

This time, as Norman Kraemer, a resident of Maplewood Nursing Home, tells it, Barbara was not to be denied. She shattered the window of a private room normally inhabited by two elderly women who were thankfully down the hall having lunch and hopped over a 3-foot concrete wall. Kraemer said the elephant trucked right on through the ladies’ boudoir, through the door, and out into the main hallway bisecting the nursing home.

The accommodating Mr. Kraemer gave me a guided tour of Barbara’s route on Sunday afternoon. Once in the hallway, the elephant turned right and headed for the main nurses’ station directly down the corridor. For some miraculous reason, the headstrong beast — “No, she’s really a sweetheart,” insisted Judy Carr — skirted the nurses’ station and didn’t so much as ruffle a piece of paper. In her wake, Barbara the elephant, who was evidently taller than the ceiling, left behind bent steel ceiling supports, tore out most of the overhead electrical wiring, and brought most of the ceiling tiles tumbling down. The place looked like an elephant had run through it.

Meanwhile, as she headed for the large exit sign to the south, Barbara paused to make a 90-degree turn into a private room at the end of the hallway where one Harley Hanick, an elderly gentleman with an everlasting devotion to the Green Bay Packers, was watching football on TV.

Harley explained—with the sort of understandable outrage that anyone would feel if the Packers game was rudely interrupted—that the sudden intrusion “was pretty nearly like a tornado, what with all that goddamn racket and all. I went to see just what the hell was going on and walked right over to the door and then this goddamn elephant sticks its head right inside. I slammed that door pretty quick and changed her direction fast enough, you bet!”

Barbara, having had that unfortunate run-in with the hot-headed Harley, now veered to the west, used her trunk to depress the bar across the door leading to the back of the nursing home, and was out in the open air once again. She rumbled along for another mile or so, decided she had seen enough of the local sights, and was captured in a cornfield.

Mrs. Josephine Roos, who is 82, was sitting by the window in her wheelchair, close to where Barbara made her entrance into the nursing home. She is an uncommonly calm human being. She said that the arrival of the elephant had brightened up an otherwise dull Sunday afternoon. “All my life I had to travel to see the circus,” deadpanned Josephine, who could have stepped out of a Grant Wood painting, “but today it finally came to me.”

Remarkably, not a single hair on a single head was disturbed during the chase and capture. In fact, late Sunday afternoon, there was an air of absolute festivity at Maplewood.

Two elderly gents standing by the reception desk swore up and down — between turns at poking one another in the ribs — that they would never take a drink again.

And a lovely little white-haired wisp of a lady, watching television in a room just off the main corridor, said to me: “This kind of thing is nothing new to us. Have you seen the size of some of the people around this place? Lots of elephants come here to retire.”

For his part, Mr. Bowman, the circus manager, took a practical view of the incident: “It’s not the kind of publicity we prefer, but if people didn’t know we were here before, they sure know it now.”

The Ordinary Life

We had a singularly inspiring English professor when I was an undergraduate at Colgate University. His name was Jonathan Kistler. He taught a popular course on Shakespeare. I approached him for advice in my junior year after I landed a microscopic role in the university theater’s production of Hamlet. For a week or so, I contemplated a career on the stage. He was generous and encouraging, even though I was pretty sure he thought I was better suited for a career in plumbing supplies. The experience ended up crushing my theatrical ambitions flat but it did have a couple of unforeseen benefits: I can still recite most of Polonius’s advice to Laertes (“Neither a borrower nor a lender be,” which I’ve used with limited success in counseling my children) as well as Hamlet’s sad soliloquy (“I have of late — but wherefore I know not — lost all my mirth”), which once got me a date with a really charming lady from Virginia who was mad for Shakespeare and momentarily mistook me for Laurence Olivier. It could have been the beer.

Anyway, Professor Kistler had a rare gift that, in my experience, only a precious few teachers possessed — he made his subjects come absolutely alive in the classroom.

Two years after I graduated, Kistler was invited to give the commencement address at Colgate. He told the seniors that, while he had personally attended something like 45 commencement speeches through the years, he could only remember one — a three-paragraph summary that he had come across in the New York Times. It made a simple point: Great success was sure to come, the speaker had assured his young audience, but it was probably more important to deal with the inevitability of failure.

Kistler recommended three books for the graduates to read: The Education of Henry Adams by Henry Adams, Reinhold Niebuhr’s The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, and Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The professor extracted important life lessons from each of these great books — lessons about how you might as well accept that human life is basically unpredictable and frequently unintelligible; that no man can “claim a genuine optimism unless he has first come to grips with this thing called pessimism”; and that — my personal favorite — in learning to accept people the way they are (as ordinary human beings) we learn to accept our ordinary selves.

But he liked Dostoyevsky’s take on living best: “It can make us see the extraordinary quality of what we usually think of as the ordinariness of life, the life we are living day-to-day: eating and drinking and talking … and the shopping and the tuition payments and the children. And all of our successes, which you know are good things to have, and all of our failures, which are inevitable.”

Kistler concluded his send-off better than anyone ever ended a commencement address before or since: “The novel can best immortalize the ordinary life, the kind of life your parents have led, and the kind of life you, too, will no doubt lead eventually. It is the kind of life that perhaps in the end breaks your heart, but it will fill your heart before it breaks it.”

My mother would say it’s a good trade-off.