Four alumni helped compile the nation’s biggest-ever report on the effects of climate change.

Each autumn, states across the Northeast prepare for two things: the brilliant fall foliage and the hordes of tourists who come to see it. But patterns of leaves may be changing due to climate change, putting that economic boost at risk. “There is a whole tourism industry in New England based around seeing red leaves in October,” says Ellen Mecray ’90, regional climate services director, Eastern Region for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). And what happens to the economy if warmer winters hurt skiing conditions, or a warmer spring impacts maple syrup yields?

Those questions and more are addressed in the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a massive government report examining how climate change is affecting our country’s economy. Impacts on maple syrup and leaf-peeping are just the tip of the (melting) iceberg of its findings, which projects hundreds of billions of dollars in economic effects on agriculture, coastal infrastructure, human health, and transportation by the end of the century. “The report is more important than ever in serving as a conversation starter with communities about what kinds of impacts there are and how we can build resilience based on those impacts,” says Dan Barrie ’05, a program manager at NOAA, who was on the report’s steering committee and helped co-write its overview chapter. Mecray co-wrote the chapter on energy and was the lead federal author on the chapter on the Northeast Region.

Barrie and Mecray aren’t the only Colgate alumni who worked on the report. David Reidmiller ’01 oversaw the entire report as the director of the National Climate Assessment for the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), while Natalie Bennett ’16 served as an adaptation and assessment analyst at USGCRP and coordinated the development of a number of chapters.

Nationally mandated by Congress, the report was a monumental undertaking, requiring four years and the work of hundreds of authors and administrators to complete. “We were trying to come up with a consensus across a very broad community of scientists and an evolving body of literature all superimposed on an evolving climate system in the background,” Barrie says.

The first volume examined the current state of scientific knowledge on climate change in America, for the first time determining the role of climate change in specific extreme weather events in a National Climate Assessment. “We can look at the science of hurricanes and put it in the context of what we know about the strength and severity of them to make attribution statements, which is a major scientific advancement,” Mecray says.

The second volume focused on specific effects climate change is already having on communities. “Rather than starting with the science and interpreting what that means, we started with observations of impacts already occurring in the environment and then attempted to explain those with science,” she explains.

That emphasis served two goals: helping to reach people who might be skeptical about climate change by showing its concrete effects and giving communities actionable information about how they could focus their resources to mitigate climate change’s effects.

“We’ve made all of these decisions based on an assumption of how the climate behaves now,” Barrie says. “As that climate is shifting, it’s going to have profound effects in ways we don’t expect based on historical precedent.”

Already, local officials have reached out to the authors to discuss strategies on how to deal with climate-related issues. In New York, for example, communities might change their snow removal budget and traffic safety plans due to projected increases of lake effect snow in winter. In West Virginia, officials are developing plans to deal with increased flooding in the river hollows. And along the coastlines, communities are assessing the strength of buildings and infrastructure in expectation of rising sea levels and intensifying storms.

“We wanted to put the best information out there so people who make decisions can have it at their disposal,” Barrie says. “They’re really craving this information, and they’re drawing on it and using it.”

A Closer Look: How Climate Change is Affecting Hamilton

While the National Climate Assessment does not delve deeper than the state level in describing physical and socioeconomic impacts of climate change, we can examine local data to see climate change effects in the region around Colgate.

According to data from NOAA, the average annual temperature in New York State has increased by about 2°F over the last two decades, with another 4° to 10° of additional warming expected by the end of the century, depending largely on the level of continued emissions of greenhouse gases. That average change, in addition to increased variability in temperature, will impact the agricultural sector, particularly during the critical spring growth season. Extreme precipitation events have also increased in frequency and strength throughout the Northeast, potentially leading to issues with springtime planting and stressing transportation, industrial, municipal, and other infrastructure.

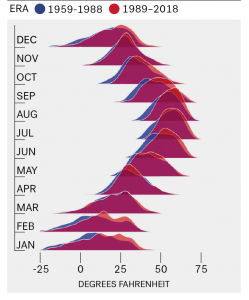

While many factors aside from climate change can impact the variability of local climate, some long-term trends are apparent. For example, a measurement station in Norwich, N.Y., (20 miles south of Hamilton) shows a lurch toward warmer nighttime temperatures in the last 30 years (1989–2018) versus an earlier 30-year period (1959–1988) (Figure 1). Students lucky enough to enjoy a summer on Colgate’s campus may find themselves needing more air conditioning on increasingly warm July and August nights.

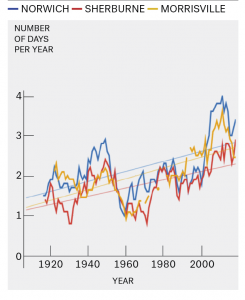

Three measurement stations near Colgate also show a clear increase in the heaviest rainfall events (Figure 2). In the early 20th century, you would expect only 1.5 to 2 days per year with more than 1.5 inches of rainfall — a significant storm for central New York. Now, such events happen approximately three times per year — with further increases expected — potentially causing increased flooding, which could strain infrastructure and impact agricultural productivity.

Snowfall patterns in the region are changing as well, in complicated ways. While measurement stations west and northwest of campus show a clear increase in annual snowfall, those to the south or southwest don’t. That is consistent with an increase in lake effect snowfall, which tapers significantly away from the lakes, but sometimes reaches as far as Hamilton. Although temperatures are rising around Colgate, the area experienced as many snow events in the last 30 Mays as the previous 30. So Colgate students may want to hold on to their coats through graduation, for now.

— Dan Barrie ’05