Among the pivotal points in these alumni’s lives, fellowship and scholarship opportunities played an integral role.

Moved by a Moment in History

From retirees’ uncertainty of the U.S. social security system to farmers’ dairy concerns, Rep. Antonio Delgado ’99 (D, NY-19) fielded a range of questions that constituents posed during his seventh town hall in mid-February. “I am here to serve you,” Delgado told an audience gathered in the Canajoharie High School auditorium, not far from where he grew up in Schenectady, N.Y.

“Irrespective of party, I want to be in the best position to take your issues back with me to D.C. and be an advocate, but the only way I can do that is if we’re having a conversation,” he added. Advocacy has been a guiding principle for Delgado throughout his diversified career, which has included titles of hip-hop artist, lawyer, and now congressman.

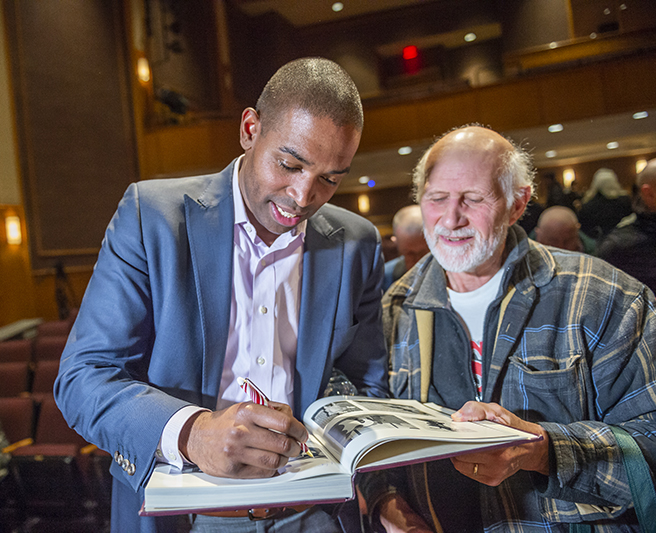

Rep. Antonio Delgado ’99 signs a yearbook for Tom Slocum whose daughter, Jenny Slocum ’99, graduated with Delgado, during a town hall at Canajoharie High School.

A political science and philosophy major at Colgate, Delgado “was always politically minded,” he says.

After graduation, a Rhodes Scholarship enabled Delgado to earn a second degree in philosophy, politics, and economics at the University of Oxford in England. Being in a foreign country on his own, so far away from his upstate New York base, helped Delgado figure out who he was. “To bury myself in knowledge, learn for the sake of learning, and get a better sense of who I am — it had a profound effect on how I came to know myself,” he says.

He then entered law school at Harvard University, from which he earned his JD in 2005. “I wanted to take my background in philosophy and have it apply more practically to the real world,” Delgado explains. His next move, to Los Angeles to pursue a music career, may seem like an unexpected career decision, but “it felt very real and true to me,” he says. “I felt that it was imperative, in light of my own academic success, to elevate a conversation within hip-hop for the purpose of talking about socially, politically important matters. I followed my heart.”

But, the lifestyle of a struggling artist began to put a strain on Delgado after several years. At the same time, he began reconnecting with his girlfriend, Lacey Schwartz, whom he met at Harvard. Schwartz was still living on the East Coast, so in 2011, Delgado proposed and rejoined her in the state where they both grew up (her hometown is Woodstock). Harkening back to his law degree, Delgado joined the firm Akin Gump Straus Hauer & Feld in Manhattan as a complex commercial litigator. “I wanted to understand the language of finance and capital,” he explains. In addition, Delgado took a number of pro bono cases, including a client who had been unfairly sentenced to life as a young teenager.

Delgado was on track to soon become a partner in the firm. But, “that wasn’t the identity I had of myself for the indefinite future,” he says. Meanwhile, he and his wife — who, by that point, had twin baby boys — had been talking about moving upstate to be closer to their families.

In 2016, the couple’s talks of future goals and dreams snapped from the realm of possibility to urgency. The presidential election, Delgado says, was an awakening. “We were already at a crossroads, and it was a moment of clarity, a moment of accountability.” He told himself, “If you have any real intentions of serving in the way you want to serve, now’s the time to live that life.”

They started by looking at towns upstate where they’d want to live — considering school districts and proximity to their families — before moving to Rhinebeck. While commuting to the city and continuing work at the firm, Delgado began assessing the possibility of a campaign. “The climate allowed for it,” he determined. “As we saw across the country, so many folks were called to action. There was a thirst for a new kind of leadership. And we were able to embrace that.”

In the 2018 midterm elections, Delgado challenged Republican incumbent John Faso for the 19th District of New York. The race drew national attention because it was considered one of the most hotly contested in the country. The district’s constituents are one-third Democrats, one-third Republicans, and one-third independents. “It was a grueling endeavor, but incredibly rewarding,” Delgado says.

Because his district is the third most rural nationwide represented by a Democrat (and eighth overall), Delgado requested appointment to three House committees that correlate with his region’s priorities: agriculture, transportation and infrastructure, and small business. Some of the issues he is tackling include green jobs, infrastructure, health care, water contamination, and rural broadband access.

When not in D.C., Delgado has been holding town halls in the district’s 11 counties, where hundreds of people have shown up to hear the congressman speak and ask him questions.

“People are frustrated with how broken the system is,” he says. “I came in during the longest shutdown in government history, and people are wondering what’s going on. The seams are coming undone, and that affects how we prioritize what we can accomplish as a country.”

Back at the town hall in Canajoharie, Delgado concluded by reminding the people that he works for them. “A big reason why I thought it was important to serve politically had to do with moral imperative,” he told the audience. “We’re leaving a lot of communities behind… In this moment in our history, more than ever, we have to find out what we’re truly about as a country and what we, as individual citizens of this great country, can do to make sure it continues to live up to its promise [of] equal opportunity for everyone.”

— Text by Aleta Mayne; photos by Mark DiOrio

Rep. Antonio Delgado ’99 is Colgate’s 2019 commencement speaker and will be recognized with an honorary doctorate.

Developing New Perspectives

Whether it’s whalers in the Azores, people experiencing homelessness in Seattle, or monkeys in Thailand, Gemina Garland-Lewis ’08 immerses herself in her subjects.

She is a photographer-researcher-explorer who’s found her niche in the One Health field, which focuses on the intersection between the health of humans, animals, and the environment. As a multihyphenate, she has designed a career that involves juggling numerous projects.

Garland-Lewis’s Watson Fellowship experience laid the groundwork for several of these projects. And another Watson Fellow, Lindsay Mackenzie ’05, connected her with National Geographic, which has supported much of her work as a photographer and explorer.

Photo by Krista Rossow

Learn more from Garland-Lewis herself:

I became a photographer when I was 12. My grandfather, a hobbyist photographer, gave me a camera, and I got hooked. I spent most of high school in the darkroom. I started exhibiting my work when I was 15, and that was my first, longer-term documentary project. It was of the Cerro Grande Fire in northern New Mexico, which is where I’m from. That’s where I got most of the background into the type of photography I do today and the belief that one could merge science and storytelling in a meaningful way.

My degree at Colgate is biology and environmental studies. Throughout my senior year, I worked on an independent study with Professor Frank Frey to better understand human disease transmission to mountain gorillas, a critically endangered species. It was a continuation of work I started my sophomore year with Conservation Through Public Health in Uganda, which I was introduced to in my medical geography course.

My Watson Fellowship was an exploration of different cultural relationships to whales and whaling. I was in the Azores, South Africa, New Zealand, Tonga, Japan, Norway, and Argentina. I worked with whale researchers, whalers, and whale-watching companies. I was looking at economic transitions from whaling to whale watching, the simultaneous existence of both whaling and whale watching, how whaling ended in some places, and what it was used for — subsistence, spiritual, economic, commercial. I also looked at regulations on whale watching around the world and the impacts on whale populations from these operations.

People tend to be confused why I was interested in whales, given that I grew up in the high desert, but I think sometimes the absence of something can make you even more curious about it. One of my study abroad programs at Colgate was doing SEA Semester, and I had a class on maritime studies. I started reading more about the history, regulations, and controversy of whaling.

“Even though my grant work wrapped up a number of years ago, the story continues and evolves.”

Gemina Garland-Lewis ’08

The Watson has influenced my career more than anything else. My first country during my Watson was the Azores, a group of Portuguese islands that were pivotal during the American and British whaling era in the 1800s. My National Geographic grant was to return to the Azores and to do a photo-ethnography of the last living former whalers.

Even though my grant work wrapped up a number of years ago, the story continues and evolves. I moved back to the Azores in late 2017 for a few months to work on a book that’s still in the works. As this work progresses, I’ve become interested in the younger generation’s ability to maintain a cultural connection to whaling and to the whaleboat without actually hunting whales. The boats are these gorgeous 40-foot wooden canoes and now the younger generation uses them for sport. I’ve spent time with the teams and sailed with them. I did a piece for National Geographic Adventure last year about that.

I went to grad school at Tufts and then started working at the University of Washington (UW). One of the people who guest lectured in my master’s program started the Center for One Health Research at University of Washington. After graduation, I worked there for three years, and then a little over two years ago I was laid off when the grants I had been funded by ended. I actually appreciated it, because it allowed me to focus on photography more. I still work with that team in a part-time capacity and teach three class sessions in a mixed undergraduate/graduate-level course, for which I’ve developed case studies through integrating work as a photographer and on the research and education side.

Gemina Garland-Lewis’s photo of whaleboats in the Azores

One of the main projects I am currently working on is [with] people experiencing homelessness with pets in Seattle. I have a long-term documentary photography project on the human-animal bond in homelessness, called “Everything to Me.” Told with partner organizations, it’s visual storytelling, research, clinical care, and education all working together. One of the case studies I teach at UW is about this, which I love because these are actual people in the students’ community. [I also] run a participatory photography component where I work with people who are experiencing homelessness with their pets to show their experience through visual storytelling.

Last year, I moved into Tent City 3, one of Seattle’s city-sanctioned homeless encampments, for about eight days, slept in one of the tents, and focused on people with animals. That was an important experience for me as a photographer to be around for some intimate moments and to get to know people better. But even living in a tent city, it’s still my voice sharing their experience. So, the participatory end of this is giving people cameras to document their own lived experience. We’ll have a public exhibit at the end of the project.

Storytelling is a great foundation. Time and time again with this project, I’ve seen people engage with the images or the stories, and they approach me to talk about how much it has shifted their perspective and gotten them involved in important issues in their communities.

— Interview by Aleta Mayne

Making His Case

The insanity defense is one of the trickiest aspects of criminal law. On the one hand, a person clearly commits a serious crime; on the other, he doesn’t seem responsible for committing it.

“The dominant definition is that someone lacks the capacity to tell right from wrong,” says Cornell University law professor Stephen Garvey ’87. But that explanation seems inadequate in some cases, Garvey argues in a recent research paper, in which he takes a deep dive into the philosophy of delusion. In some cases, a person may know they’re doing something wrong, but not feel like they’re the one doing it. “When people form delusions, there is a defect in their sense of agency,” Garvey says. “When someone commits a crime in that case, are they the author of what they are doing?” Those are the kinds of subtle but weighty questions Garvey has wrestled with as a scholar of criminal legal theory.

Stephen P. Garvey ’87, a professor at Cornell Law School, is pictured at the Cornell law library in Ithaca, N.Y. Photo by Mark DiOrio

At Colgate, he was inspired by a first-year seminar taught by Joseph Wagner, tackling the most controversial issues — such as abortion, the death penalty, and affirmative action in a way that went beyond political ideology of right and left. “He was especially effective and inspiring in terms of pushing you to think self-critically, with an emphasis on self,” Garvey says. “He believed that if we think long and hard and critically enough, we can come up with some answers.”

Garvey continued that practice of examining big questions as a Marshall Scholar, an honor awarded by the British government to study at Oxford University. Garvey pursued a master’s of philosophy in politics, thriving on the intensity of the Oxford tutorial system, in which small classes delve into topics with rigorous discussion. He took legal and political theory classes and studied philosophers from Marx and Hegel to Hart and Dworkin. “I had the time and opportunity to read and think. That’s a real gift.”

The experience convinced Garvey that he wanted to teach law, and after clerking for a judge and working at a Washington law firm, he was offered a job at Cornell in 1994. Much of Garvey’s early work centered on capital punishment, going beyond the morality of sentencing a person to death, to focus on the state of mind of those doing the sentencing. Based on surveys of nearly 200 Virginia jurors in capital cases, Garvey found a wide range in their likelihood to impose the death penalty based on race, religion, sex, and other factors. Those eye-popping discrepancies showed how arbitrary capital punishment can be, calling into question whether the state should be allowed to impose it.

Since then, Garvey has continued to look into the philosophy of criminal justice, examining questions of self-defense, the heat-of-passion defense, and alternative sentencing. He is currently working on a book examining the moral limits on the state’s authority over the criminal law called Guilty Acts, Guilty Minds. (The book is dedicated to “two Joes” — Wagner, who passed away in 2016, and to Garvey’s father, who passed away the following year.) In all of his scholarship, Garvey has followed the methods he learned in Wagner’s seminar: diving deep into the literature on a topic and not being afraid to question his own assumptions.

— Michael Blanding

Global Citizen

Follow this Fulbright winner’s path around the world.

Getting Into the Rhythm of Research

A molecular biology major at Colgate, Amanda Liberman ’17 researched the connections between people’s circadian rhythms and mood disorders. Mentored by professors Ahmet Ay and Krista Ingram, she and some of her fellow students looked at where participants fell on scales of anxiety, depression, and morningness-eveningness. Liberman’s role was designing mathematical models to represent this relationship.

The team later published their research in two scientific journals. For Nature Scientific Reports (August 2017), “we were able to show that a gene called PER3 is related to both circadian rhythms and to anxiety,” Liberman says.

In a follow-up study published in the Journal of Biological Rhythms (April 2018), the researchers found that “several circadian clock genes were linked to depression and other mood disorders,” Liberman explains.

As Colgate’s first Beckman Scholar, she received 15 months of funding to support her research and present at research conferences, including the Gordon Chronobiology Conference and the European Biological Rhythms Congress in Amsterdam.

A Year in Siberia

At Colgate, Liberman was a 1819 Award winner and a Max A. Shacknai Volunteerism Award winner.

Photo by Andre Chung

Moving to Kazakhstan after graduation was “like arriving on a new planet,” Liberman says. She didn’t understand all of the cultural references, and the extreme cold froze the moisture in her eyes and eyelashes. Fortunately, Liberman had a firm grasp on the language — which is part of how her Fulbright Scholarship came about. Liberman speaks Russian, both because her father emigrated from Russia and because she was a Russian and Eurasian studies minor. She had previously visited Kazakhstan during an extended study with the class Authoritarian Capital Cities of Eurasia as a first-year. Still, moving there on her own was an entirely new challenge.

From August 2017 until May 2018, Liberman lived in Semey, Kazakhstan, teaching 10th-grade biology. She was helping to implement a new national educational policy requiring that science classes are taught in English. “This is a major change for the country,” Liberman explained. Previously, science classes were taught in the local language of the school, usually Russian or Kazakh. Liberman also volunteered as an English teacher at the local library and as a Russian-language first aid instructor at the local Red Crescent. When the school year ended, Liberman moved to the southern town of Kaskelen to finish her Fulbright at Suleyman Demirel University. There, she taught first-year college students English for Cytology and Histology, which involved scientific vocabulary and lab terms.

Learning how to adjust to a different culture was the ultimate lesson for Liberman in her current life and as she looks toward the future. “Especially when I become a doctor,” she says, “I will be dealing with people who come from cultural backgrounds that could be really different from my own.”

Looking for a Cure

Now, as a research fellow at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Liberman studies prion diseases, which are a type of neurogenerative conditions that are fatal and incurable. Research into these diseases also has potential applications for other neurogenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and dementia. Liberman and her colleagues are studying heat shock proteins to try to understand how they help cure these diseases in yeast, which they hope will inform a solution for humans. Her one-year research fellowship in Bethesda, Md., concludes this July.

When not in the lab at the NHLBI, Liberman has continued her volunteerism on the National Sexual Assault Hotline. This is a continuation of the work she began as a Colgate student. While at Colgate, Liberman received her rape crisis counselor certification and volunteered with the Help Restore Hope Center’s sexual assault and intimate partner violence hotline.

Back to School

In the fall, Liberman will attend Yale School of Medicine. She’s considering specializing in obstetrics/gynecology because she has a strong desire to promote women’s health. “As a rape crisis counselor, I spend a lot of time working with survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence,” she explains, “and these issues are important to me.”

— Aleta Mayne

PeaceKeeper

Afghanistan has seen ongoing conflict for at least the past 40 years — ever since the Soviets invaded in 1979. Despite the decades of violence, including invasion by the United States in 2001, the country may be closer now to peace than it has been in years.

“The combination of fatigue about the war on all sides, and the motivation by the United States to seek a political solution, adds up to some cautious optimism that there can be a different way forward,” says Scott Worden ’96, director of Afghanistan and Central Asia Programs at the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP).

“For the first time in many years, there is an opportunity to move toward a peace process that can provide a lasting settlement.”

Scott Worden ’96

It’s Worden’s job to analyze the prospects for peace in the region and to actively work to make it a reality. Established by an act of Congress as an independent, nonpartisan institution, USIP has helped to prepare Afghanistan for elections and reduce conflict on a local level, at the same time reporting on larger trends nationwide. “Writ large, we provide conflict analysis and ideas on policy as well as practical solutions that can be implemented on the ground,” Worden says.

Scott Worden was a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Junior Fellows Program while he was an undergraduate at Colgate. Photo by Andre Chung

Growing up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., Worden was always close to politics. His father worked for the General Services Administration, and his mother was a civilian employee at the Department of Defense. At Colgate, Worden pursued an interest in government as a political science major and an interest in journalism as an editor of the Maroon-News. He first became fascinated with issues of international peace and conflict though participation in the semester-long Geneva Study Group in 1994, studying the Balkan conflict, which was happening at the time.

Afterward, he studied with Professor Martha Olcott, one of the foremost experts on Central Asia, who suggested he apply for a fellowship at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace following graduation. There, all of Worden’s interests came together. He was an editorial assistant for Foreign Policy magazine and took advantage of the think tank’s high-level events and programs. “It exposes you to a broad range of policymakers and academics,” he says. “I got to sample a wide range of the policymaking environment.” The experience shaped his path at Harvard Law School, where he focused on the rule of law.

Now at USIP, he spends much of his time in Washington, visiting Afghanistan for a couple of weeks per quarter. Through the organization’s field office in Kabul, he has helped to train local civil servants on how to reduce conflict in their communities, and he’s worked with the Afghan government land authority to resolve disputes over property titles, which can be a major source of violent conflict. In addition, USIP has partnered with several Afghanistan universities to teach a course on peace and conflict resolution and piloted radio shows to allow the local population to address local corruption and bad governance.

Worden sees the new effort by the United States to open direct talks with the Taliban, led by U.S. special representative Zalmay Khalilzad, as a positive step toward ending conflict in Afghanistan. “For the first time in many years, there is an opportunity to move toward a peace process that can provide a lasting settlement,” Worden says. Of course, many obstacles remain — first and foremost, the Taliban’s unwillingness to recognize the legitimacy of the Afghan government. But by facilitating talks with representatives of diverse political and ethnic factions, the United States can potentially break the stalemate between the Taliban and the Afghan government and move toward a more representative government and a sustainable peace. “The United States has changed its position in a productive way,” Worden says. “But resolving the underlying political dispute is a conversation that needs to occur among the Afghans themselves.”

— Michael Blanding

Read about some of this year’s fellowship and scholarship winners at colgate.edu/news.