More than a year and a half after Lucy Usoyan was brutally attacked in Washington, D.C.’s Sheridan Circle, she is still impaired from her head injuries. Usoyan had been part of a protest against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on May 16, 2017, in front of the Turkish ambassador’s residence. At that peaceful protest, Turkish security officers, without provocation, attacked the demonstrators. Nine people were hospitalized.

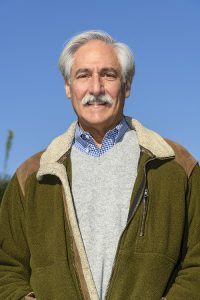

Attorney Douglas Bregman ’71, on his way home from work, was listening to the news reports on the radio. “My reaction was visceral,” says Bregman, who is a partner at the Bethesda, Md., law firm Bregman, Berbert, Schwartz & Gilday. “These folks were getting beaten up for exercising their First Amendment rights, in Washington, D.C., of all places. This was wrong.

“As a lawyer, I thought I could put my skills to work to remedy the wrong,” adds Bregman, who has felt the call to activism since his student days. That night, he called Andreas Akaras, a lawyer in his firm who previously served on Capitol Hill as a foreign affairs adviser.

Through Akaras’s connections with Kurdish American community leaders, he and Bregman met several victims of the assault. Usoyan — who suffered traumatic brain injury from being kicked in the head during the incident — is the first one named in their civil suit against Turkey.

For the attorneys to be able to advance this case, they must establish that it falls within an exception to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, which is a law that limits U.S. suits against foreign governments. One of the claims asserted against Turkey is that the assault constituted an act of terror that transcends national boundaries. Admittedly, “it’s an exceptional circumstance and untested argument,” Bregman says. “This case may make new law.”

At press time, the attorneys were in the process of serving Turkey with the lawsuit. There has been a delay because, while Turkey is a signatory to the Hague Convention, it has refused to accept service of the lawsuit complaint through established methods. As a result, the lawsuit will be served by the U.S. Department of State, which is a notoriously slow process. “Turkey’s tactics to delay justice only further emboldens our resolve,” Bregman says. “[Turkey is], in theory, a NATO ally, but how the Erdoğan regime conducts itself in this lawsuit will certainly have an impact on their relationship with our country.”

Despite the initial challenges with the case, the attorneys and their clients have received an outpouring of support from Turkish citizens who oppose the actions of Erdoğan and also from Washington’s diplomatic community.

The U.S. House of Representatives unanimously approved a resolution calling “for perpetrators to be brought to justice and measures to be taken to prevent similar incidents in the future,” and senators and congressmen have passed proclamations criticizing Turkey. “Unfortunately, the Trump administration has been uncharacteristically quiet,” Bregman says, “and for some mysterious reason, following a meeting between former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, charges were dropped against eleven of the fifteen Turkish security agents who had been charged.”

As Bregman looks at a lengthy legal battle, he says he’s willing to put in the time and resources (even though he fits this case in among his professorships at Georgetown Law [his other alma mater] and Columbia University as well as juggling his commercial real estate and business caseload).

“An important part of this lawsuit is sending a message,” he emphasizes. “The leaders and people of other countries are going to be held to our standards of decency and civility while they’re on our soil. Our right to free speech and demonstration will not be inhibited by any country.”

If he could see himself now, the Colgate student version of Douglas Bregman — a political science major who participated in the 1968 campus sit-in and antiwar protests in the nation’s capitol — would be proud.