If the pipes, wires, and other systems that make life run smoothly confound you, you’re not alone.

“There’s this mysteriousness or magic that’s associated with infrastructure,” says Chris Henke, associate professor of sociology and environmental studies.

Henke is interested in what makes these systems stay invisible when they’re running smoothly. He especially wants to understand how people respond when the magic fails and things fall apart. That’s why he and his co-author Benjamin Sims, a sociologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, have written a new book about infrastructure. Specifically, fixing it. Their book, Repairing Infrastructures: The Maintenance of Materiality and Power (MIT Press), came out in 2020.

To the authors, repairing infrastructure doesn’t just mean filling in potholes. Henke and Sims discuss processes big and small, involving structures ranging from massive bridges to individual airplane seats. The term “infrastructure” includes both physical structures — the roads and pipes and buildings — and the social structures intertwined with them, Henke says. And when those structures break down, the stakes are greater than just smooth roads. Infrastructure repair can raise questions of power, perception, and privilege.

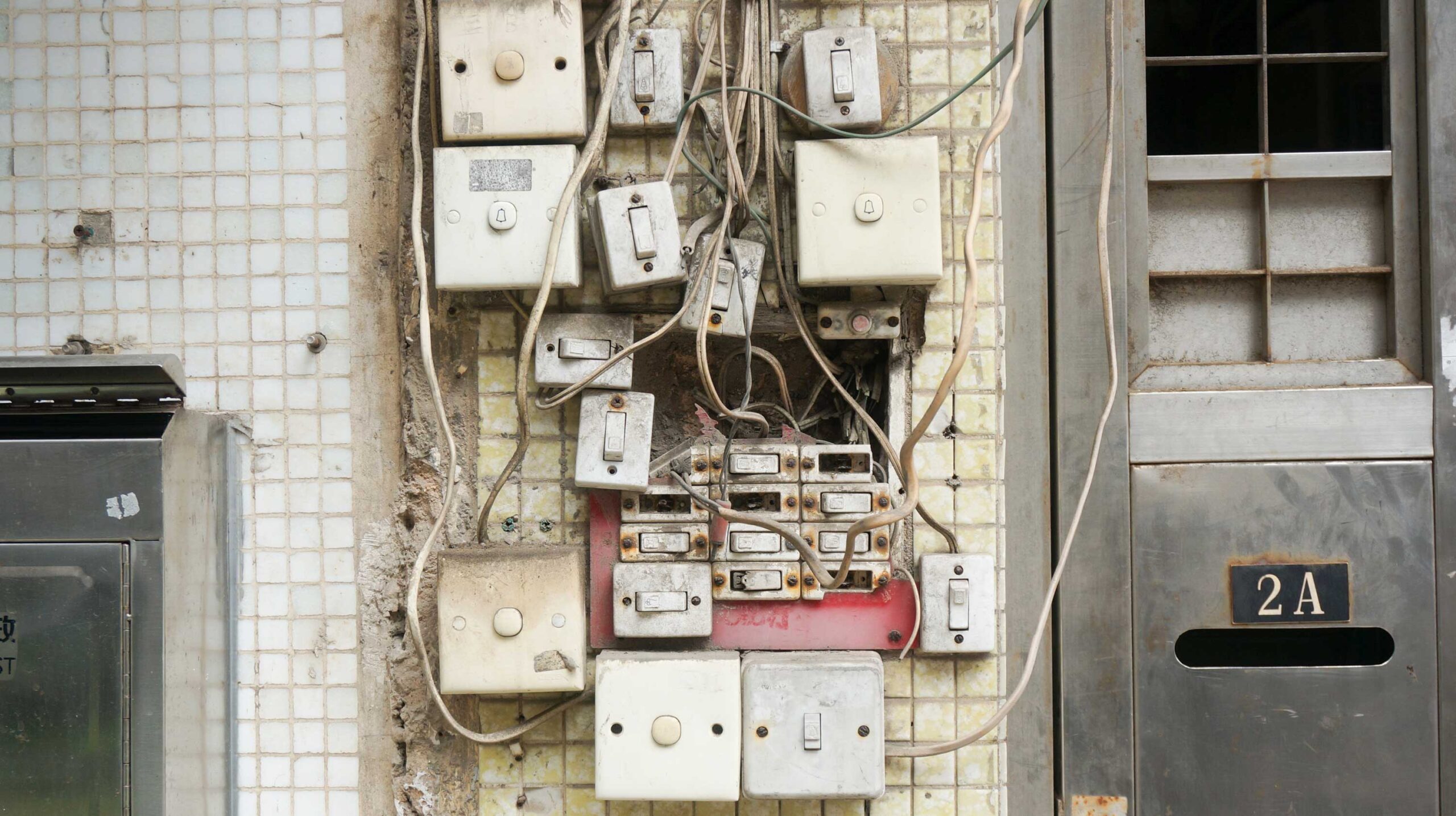

When your water and electricity arrive anytime you need them, it’s easy to ignore the systems that make that happen. In parts of the world where the electricity is always on the fritz or the water’s unreliable, “it’s not quite as magical,” Henke says.

In their book, Henke and Sims explore examples including Louis XIV’s Versailles, New Orleans’ levees, public transit, the Panama Canal, the state-of-the-art Trudy Fitness Center on the Colgate campus, and the internet itself. Their case studies show that repairing something — or even deciding whether it’s broken — can be far from straightforward.

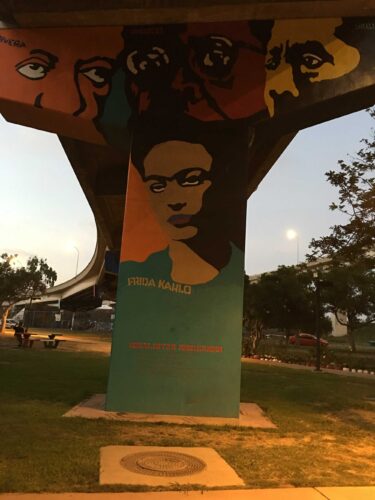

One of those stories is about the San Diego–Coronado Bridge. It stretches more than two miles across the bay to connect San Diego with the wealthy city of Coronado. When the bridge was constructed in the 1960s, it ran right through a Mexican-American neighborhood on the San Diego side called Barrio Logan. But throughout the several years that followed, artists from San Diego and beyond repaired the neighborhood by painting dozens of striking murals on the bridge’s support columns. The site, called Chicano Park, would eventually become a National Historic Landmark.

That wasn’t the end of the story, though. In 1995, state engineers decided the San Diego–Coronado Bridge’s columns needed retrofitting with steel jackets to protect against earthquakes. But that would mean covering up the murals. Engineers “thought they were trying to solve a technical problem,” Henke says, “but were enmeshed in this set of politics and controversies about how to best fix this bridge at the same time that you would preserve an important landmark and source of cultural pride.” Eventually, the engineers found a solution that would make the bridge safer while mostly sparing the murals.

Not all repairs are so complicated. We fix the systems around us every day, Henke says. In his own house, there’s a sticky old door that only opens if you kick the bottom and raise the latch at the same time. His family doesn’t even notice anymore. “If you think about all those little bits of repair that we do in our life, it is going on all the time,” he says. “It adds up to a lot of different practices and habits that we have that help us get through the day.”

Henke first started exploring the subject of infrastructure repair in graduate school. He traveled around campus with the university maintenance workers, observing what they did. One phenomenon he noticed, which appears in his book, is what Henke calls the cold-office problem. It goes like this: an office worker, often female, puts in a call to maintenance because the heat in her room seems to be broken. A mechanic, often male, arrives and finds the office’s temperature controls working just fine.

Part of the problem’s root, Henke says, is that office buildings have historically been designed to cater to the comfort of men. Anyone sitting and working at a computer all day might get chilly, but women’s physiology may make them especially vulnerable. For the mechanic facing the shivering female employee, repairing the problem is less about going into the ceiling with a screwdriver and more about conversation and negotiation. (People freezing in their offices may also conduct their own repairs by, say, keeping a heavy sweater at work. Or, as Henke has observed in his own building, they might drape their office temperature sensor with a paper towel soaked in cold tap water, which tricks the heat into turning on.)

The cold-office problem exemplifies the interesting questions about infrastructure repair, Henke and Sims write: “How do we really know when something is broken? Who gets to decide if something needs to be fixed?” Systems of infrastructure can determine who has power and who doesn’t — and the way infrastructure is repaired can reflect, or even change, where that power lies.

The past year has starkly illustrated some of the principles of Henke and Sims’s volume. But they finished writing it before the COVID-19 pandemic started. “The word ‘COVID’ doesn’t appear a single time in our book,” Henke says. The co-authors wondered if they should add an epilogue to address the pandemic. “It’s hard not to observe a lot of what’s happening in the context of infrastructural systems and repair,” Henke says. But they weren’t sure what they would say in such an epilogue, since the pandemic’s lessons are still playing out.

“In some ways you can say the pandemic really reveals just how fragile everything is,” Henke says. In other ways, he’s impressed that our societal systems have held up as well as they have. It will take some time to figure out what lessons the pandemic has taught about the balance between fragility and resilience in our society, Henke says. In the meantime, people are trying to figure out how to use our infrastructural systems to slow the virus’ spread, create vaccines, and distribute them to millions of people.

“There’s this giant repair project, in a way, going on,” Henke says.