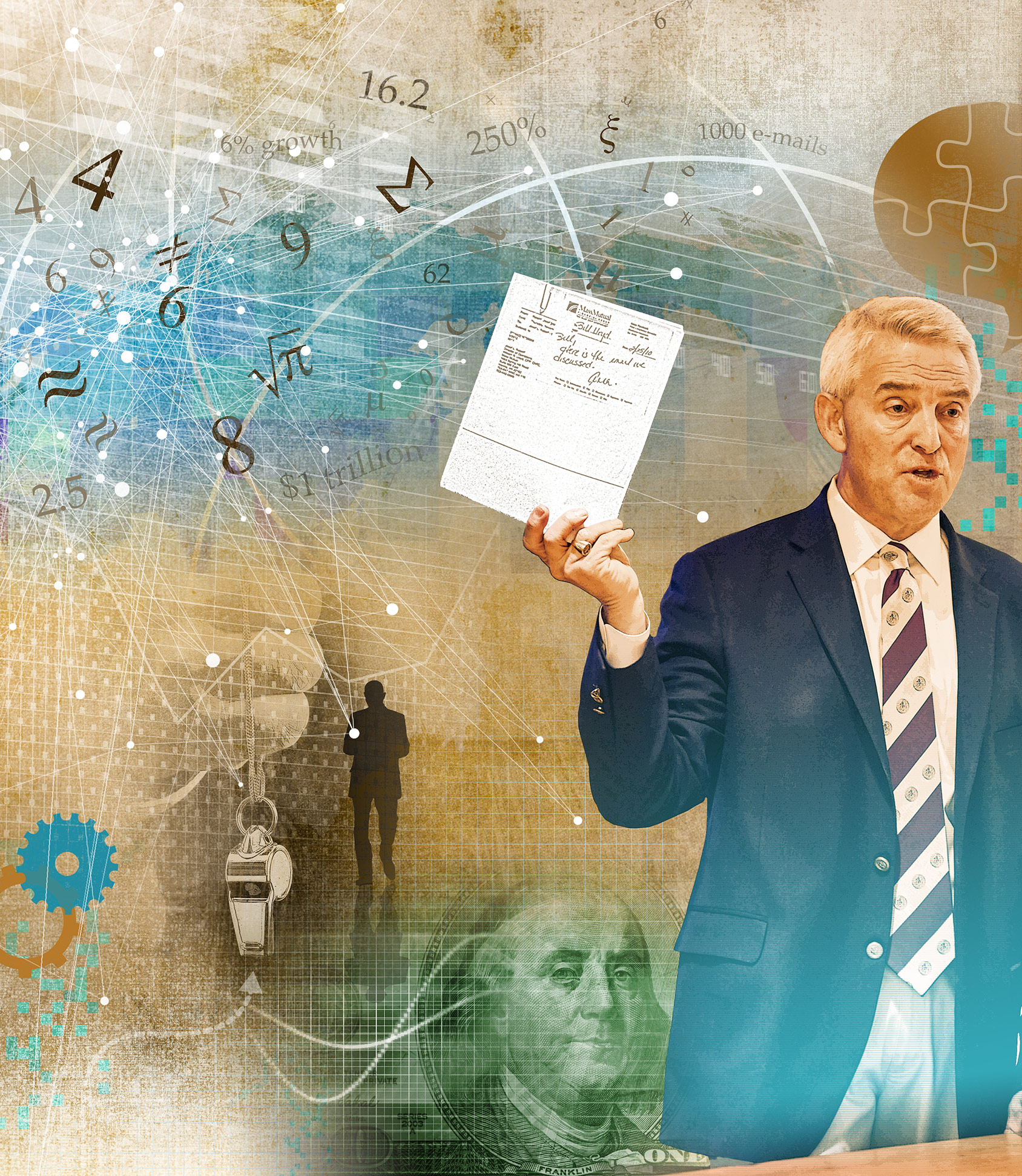

How Bill Lloyd ’80 blew the whistle and saved the retirements of thousands

It started like all their other monthly annuity study sessions. Bill Lloyd ’80, a financial adviser and certified financial planner at MassMutual in northern Virginia, had gathered with a dozen colleagues to discuss one of their products. The group leader was puzzled by something with a new annuity that they’d been using.

It was July 30, 2008, a year when Americans invested $1 trillion in annuity products. The guarantees that annuities provide make them popular retirement investment options, especially during major economic turmoil like the Great Recession of 2008. In what some called an annuity arms race, companies were frequently changing or adding riders, and the study group was trying to keep up so they could match their clients with the right products.

MassMutual had just introduced a living benefit rider for its variable annuities — its first — the previous September. In a nutshell, it promised no less than 6 percent compound interest on retirement income, up to a cap of 250 percent, based on the initial investment. With the option to draw an income stream at any point, at any age, the product offered liquidity and guaranteed, if limited, growth. Flexible, and safe — right?

But the markets were tanking. The group leader had a client who was very worried, a 62-year-old man who’d invested $100,000 when the product opened, and his principal had dropped to $60,000. To assure his client, he had used the new software provided to reps to illustrate how the product would protect his investment. The results were unexpected, so he had brought it to the study group.

He ran the illustration of the $100,000 investment through the 16.2 years it would take to reach the cap ($250,000, the guarantee at 6 percent growth), and then simulated regular income withdrawals with a worst-case scenario in declining principal. The protected value began decreasing at the same rate as the actual principal, right on down to zero.

“We’re like, ‘What’s going on?’” Lloyd said. “The illustration contradicted everything we had been trained on. I thought the technology was flawed.” That day, Lloyd embarked on a herculean quest. Over six years, he would risk his career — and endure 21 crimes committed against him — to not only solve a $2.5 billion math problem but also get his company to halt impending financial devastation for thousands of customers.

The a-ha moment

Puzzlement quickly became concern. “I had sold a couple of million dollars of this product, including to a family member,” said Lloyd, a man with a boyish visage and penchant for speaking in metaphors whose easygoing demeanor almost belies the gravity of his story. He’d had two decades of experience in the field after a first career teaching high school math and coaching college-level swimming.

Lloyd went to the wholesalers for clarification, but they were stumped; the internal guy at headquarters said he’d look into it. In the meantime, Lloyd began asking trusted colleagues: “Am I clueless?” Universally, folks told him they saw a discrepancy between the illustration and their training. He spent a couple months studying the problem, both the mathematics and the parameters, while awaiting word from headquarters.

Then, it dawned on him. The decline in the protected value mirrored that of the underlying investment value because the product was designed such that, once the cap was reached, every dollar withdrawn would reduce the protected value at the same rate. But nothing — not the sales materials, the prospectus, or the training — said that. On the day the cash value hit zero, there would be nothing to annuitize. No retirement income stream. The only way to preserve the protected value would be to begin withdrawing income before reaching the cap, which defeated the whole reason to buy the product. And customers likely wouldn’t realize this for at least 16.2 years.

“There was no way in hell I was going to let Leroy’s retirement get destroyed. Not on my watch.”

He began thinking about the harm to his clients. One in particular came to mind.

“There was an older fellow, a blue-collar guy outside New Orleans, named Leroy. A good man.” He worked in construction. Had put his kids through school, and supported both daughters and their kids after divorces, while taking care of his wife. She was in for surgery when Hurricane Katrina hit. Her scans were lost on the medevac to Baton Rouge, and she died. Leroy had invested $60,000.

“This guy had entrusted me with what was a big investment for him. I was raised by a Colgate graduate who’s a Marine, a Marine grandfather, and a mother who’s one hundred percent German and the toughest of the three. Gray areas did not exist,” said Lloyd. “There was right, and there was wrong. There was no way in hell I was going to let Leroy’s retirement get destroyed. Not on my watch.”

Sounding the alarm

It was now September 2008. The internal wholesaler finally called Lloyd back and confirmed his suspicions. Lloyd pointed out the omission in the materials and training. “I’m sorry. That’s the way it is,” he was told. So Lloyd went to his direct superior, the general agent responsible for all the sales reps in his territory. “He had this ‘Oh my God’ look on his face, and began contacting people at his level,” said Lloyd, who, meanwhile, talked to the wholesalers and the MassMutual Agents Association.

Eventually he was referred to a VP in the variable products division, but he heard nothing but crickets — “until I sent an e-mail with three little words in the subject line: Class Action Lawsuit. Suddenly, I was Mr. Popular. When they first responded, I noticed in the e-mail thread that one of them had a JD after his name. I thought, great, they want to solve the problem.” Lloyd asked to include two well-versed colleagues in the call.

“No. We just want to talk to you,” he was told.

“I’m thinking, this is not about exchanging Christmas presents,” said Lloyd. He told his general agent, who insisted on joining the call.

During that call, on December 4, 2008, after Lloyd described the problem, the home office attorney jumped down his throat. He declared that nothing was wrong with the product, that Lloyd had mis-sold it and should have been better supervised — and that all of the clients should have received illustrations. Lloyd knew the attorney was blowing smoke. By law, annuities do not require an illustration for sale.

We need to do what’s right and fix the problem.

“Don’t shoot the messenger,” Lloyd said. “These clients are going to get hurt. The reps will get sued. You’re about to let the financial equivalent of the Toyota car explosions happen.” After the VP responsible for the prospectus insisted they could not possibly have foreseen every circumstance, Lloyd said, “They told me I was the problem.” But he knew he wasn’t.

He found respite, and encouragement, in “chasing down my kids” (Palmer in middle school, Will in high school, and Kelly at University of Virginia) at their events. Parked outside a natatorium, he saw a friend who does class action law, and described what was going on. “I asked, ‘Am I imagining this?’ He said, ‘Oh, no, it’s very real. It will involve large sums of money and people’s reputations.’ I walked in to watch my daughter dive at regionals and miss all-American by a point, and then came back a week later at States, and she nailed it.”

Lloyd began collecting information — sales materials, prospectuses, notes from other offices — and continued trying to motivate agents association officers to bring the problem to MassMutual’s leadership. “The attorney kept trying to block me,” he said. Lloyd also began recording the name of every person he knew had knowledge of the flaw in the product on a sheet of paper — his “sacred tablet” that he carried around for the next several years. On the back, he soon began keeping track of the crimes being committed against him.

The plot thickens

Just a few weeks before that call on December 4, around Thanksgiving, the problem also became personal — and the situation more complicated — when the relative to whom Lloyd had sold the product (we’ll call him ‘Pete’) paid him an unexpected office visit.

‘Pete’ was in the commercial real estate market, which was floundering. He was in significant debt. He had a child in college. And the cash value of his annuity was down around 50 percent. With a history of violence, he was more than agitated. They argued about the promises made about the product. Although Lloyd could cite detailed notes proving he had not misled him, ‘Pete’ requested Lloyd file a claim on his own errors and omissions insurance to recoup the investment loss for him.

“He would not have known the phrase ‘errors and omissions insurance’ for all the tea in China. He was obviously coached,” said Lloyd. Things exploded, and ‘Pete’ filed a complaint against Lloyd (the first in his career). MassMutual investigated, and after Lloyd was cleared, ‘Pete’ threatened in front of others to take a baseball bat to his kneecaps. Lloyd got a protective order; sadly, the two became estranged, starting a rift in the family.

By December 2009, several top association officers, and many general agents, understood there was a problem. At that point, MassMutual gathered 25 top reps and general agents, executives responsible for the annuity, and one of the people “who has a lot of Os in his title.” When the variable annuities VP claimed that Lloyd (not by name) and an office colleague had been mis-selling the product, the agents association president protested and handed out Lloyd’s illustration showing the flaw — essentially what Lloyd had already provided. An hour-long argument ensued.

…the problem also became personal — and the situation more complicated…

“Finally, the O-man said, ‘Stop,’” said Lloyd. “He asked the agents, ‘Is this how you understood the product to work?’” They confirmed: yes, and that was also how they had been trained, and what they had sold their clients. “Then we need to do what’s right and fix the problem.”

Close to victory, Lloyd thought. But unbeknownst to him, another huge monkey wrench had been thrown in. Lloyd had recently fired an employee, and it was an ugly scene. ‘Greg’ had significant short-term debt and was living on bonus earnings, which, given the recession, Lloyd could no longer pay him. When Lloyd requested he start repaying money he’d loaned him, ‘Greg’ exploded, verbally and physically, and then wrote an e-mail to Lloyd that gave cause for firing him.

Lloyd consulted on the termination process with a Colgate friend who’s a top labor attorney, Mike Stevens ’81. ‘Greg,’ now on probation, had access to Lloyd’s online calendar. He saw the appointment with Stevens and deduced he was going to be fired. ‘Greg’ was aware of the annuity issue, and Lloyd’s estrangement with ‘Pete’ over it, and he knew how to use it.

On November 5, it turns out, he broke into Lloyd’s office at 5:45 a.m., erased his business calendar, and, in addition to other documents, stole his annuity research file, copied it, and later returned it. He took the annuity information to ‘Pete,’ who used it to extort a six-figure sum in hush money from MassMutual.

‘Greg’ used the other stolen information to falsify nine counts against Lloyd to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), four to the Virginia Securities Division, and three to the Virginia Insurance Bureau, and sought to have the Certified Financial Planners Board of Standards de-credential him. And, he committed identity theft using Lloyd’s credit card numbers and PINs.

Not until ‘Greg’ was gone did Lloyd’s boss tell him he had an FBI record: arson, armed burglary, assault with a dangerous weapon, conspiracy, and more. It’s a FINRA violation for anyone with a felony conviction to be in an office where securities are tendered. The company had known for five months; Lloyd’s boss was eventually removed for his inaction. Lloyd would have to pursue ‘Greg’ in federal court on his own.

Bringing in the cavalry

Reality was setting in: Lloyd’s credibility, and his job, were in peril. He asked MassMutual to defend him against the false charges; he was told to get his own attorney. “I need help,” he told a lawyer friend at his son’s basketball game. The friend told him, “There’s a guy named Jason Pickholz up in New York. That’s who I’d get.” Lloyd went to meet Pickholz. Must have been kismet. A top expert in securities law, he was also a fellow Colgate grad, Class of ’91.

Pickholz, who worked for years as a partner in large firms, said his financial law career was “in the genes.” His dad was assistant director of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement division; mom is an SEC branch chief, and a cousin who worked for the SEC became an elected judge. With the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and its SEC Office of the Whistleblower Award Program in 2010, Pickholz had seen the opportunity to open his own firm to focus on cases just like Lloyd’s.

“Bill was my first client in the door,” he said. “I immediately recognized there’d been a securities violation, and that the SEC should be aware of it. When Bill explained the extensive efforts he had undertaken to make this problem known internally, I understood he was a decent person who was not out to glorify or enrich himself.” Pickholz began working to clear Lloyd’s name with FINRA, which would begin rebuilding his credibility with the other entities, and with the MassMutual annuity issue — because, at the same time, MassMutual’s law division began claiming Lloyd had been engaged in wrongdoing. Suddenly, Lloyd’s allies stopped answering his e-mails, wouldn’t take his calls. Then his new boss told him, “I wouldn’t spend any more time on that annuity problem. MassMutual will deal with clients one by one.” Lloyd saw that as a veiled threat to drop his quest.

With no other recourse, Lloyd agreed that Pickholz should contact the SEC. It was early December 2010. The Dodd-Frank law was so new, its rules wouldn’t even be in place for another eight months. A week later, Lloyd walked “deep into the bowels of the SEC” with Pickholz and met with the enforcement assistant director, senior investigative counsel, and an actuary. Of the two giant satchels of evidence he’d collected (training notes, more than 1,000 e-mails, recordings of conversations), Pickholz instructed him to bring only the most important items. If the SEC was interested, they’d tell them there was much more to follow. Lloyd found himself giving a math lesson to explain the problem. It took an hour and a half.

“Bill was my first client in the door. I immediately recognized there’d been a securities violation, and that the SEC should be aware of it.” — Jason Pickholz ’91

“I was never so thankful for having been a math teacher after Colgate,” remarked Lloyd, who said he’d “majored in Al Strand and Dan Saracino. Were it not for those professors teaching me how to think in a logical and mathematically progressive style, there is no way I could have recognized the flaw in the product, and the consequences.” It took another hour to elucidate the prospectus’s problems. He’d made two illustrations, using dummy names with a sardonic twist.

“In ‘I’m Screwed,’ I showed how the product would zero out if the flaw was triggered. In ‘I Was Fooled,’ I showed what MassMutual said was supposed to prevent that from ever happening.” Unfortunately, the dramatic drop in the markets would prevent the fail-safe from ever kicking in; they’d need to average an unprecedented 16 percent gain or greater for 15 consecutive years. Compounding the flaw was the fact that, in their haste to bring it to market, the product’s creators failed to explain properly how it worked to the marketing people.

The SEC representatives “could see Bill’s conviction,” said Pickholz, “that he’s intelligent, and he clearly knew what he was talking about.”

“Thus began the whistleblowing,” said Lloyd.

Justice served

The SEC investigation went on for months. Other than a few requests for documentation, “It’s silent. That’s the killer,” Lloyd said. “Periodically, a friend would imply they had just been interviewed.” From that, he could tell where they were in the investigation.

In April 2011, with Lloyd outed as a whistleblower, a company regulatory attorney told Pickholz that Lloyd’s employment agreement superseded the protections of Dodd-Frank. Unless he agreed to participate in the company’s defense, they saw possible grounds for termination. If that happened, “I would no longer be employable in the securities industry,” Lloyd said. So he resigned, on Tax Day.

The case against ‘Greg’ also picked up steam. “We ended up in the Alexandria Federal Court with Judge Claude Hilton, who had ruled on the 9/11 bombings and the Unabomber.” The proof against ‘Greg’ was incontrovertible: he’d e-mailed the stolen documents to his wife at her workplace, through Department of Defense servers. Under a consent order, ‘Greg’ admitted everything, and Lloyd was cleared by FINRA and the other entities.

The big victory came on Nov. 15, 2012, when the SEC finally posted its findings: MassMutual had committed securities law violations, “failing to sufficiently disclose the potential negative impact of a ‘cap’ it placed on a complex investment product” that involved $2.5 billion in variable annuities. MassMutual settled, removed the cap, and paid a fine of $1.625 million. It was the first time Dodd-Frank was used proactively: no investor lost a dollar. “The SEC did their job, and they did it well,” said Lloyd.

If you don’t step up and protect other people, who’s going to do it?

But would Lloyd receive an award? After months of waiting, and having lost more than seven figures — his income, benefits, and 401(k), with attorneys’ fees looming — the news was terribly disappointing. He’d been denied. But Dodd-Frank allows for appeal. In November 2013, Lloyd and Pickholz had an intense three-hour meeting with Sean McKessy, chief of the Office of the Whistleblower, among other representatives. He’d later learn that an award committee member had drawn the wrong conclusions about whether Lloyd had voluntarily disclosed. About nine months went by.

On the afternoon of July 30, 2014, exactly six years after that annuity study meeting, Lloyd was with his bookkeeper, taking stock of his financial challenges. “I figured ‘I’m never going to get back what I lost. But it’s OK. I’m alive. I’m going to make it work.’” The phone rang. It was Pickholz: “McKessy wants to talk to you.”

“I go to my office and sit down. I’m shaking,” said Lloyd. “The phone rings, and McKessy says, ‘Bill, first, I want to thank you. You’re the reason I took this job. You were the guy who was willing to put his hand up and not let the parade go by without trying to fix it. It’s my pleasure, on behalf of the Office of the Whistleblower, Commissioners of the SEC, and the entire commission, to inform you that you’ve been awarded 25 percent of MassMutual’s fine, $406,250.’ It didn’t catch up to what I lost, but it filled in all of the divots. I was back on terra firma.” Inside Counsel named the reversal (the first and only) as one of the five milestones of the Dodd-Frank whistleblower reward program.

“Bill fits my definition of a hero,” said Pickholz. “He put his career and his own money and relationships on the line to protect people he didn’t even know. And he didn’t ask for anything.” The Colgate compadres agreed to celebrate with a beverage at the Inn during Homecoming Weekend 2014. More Colgate kismet: Lloyd was the 13th whistleblower to receive an award, which was wired to him on August 13.

“It was a long road,” said Lloyd, who in 2012 co-founded an independent firm, Parkway Financial Strategies. “It cost me a great deal. There were times, because I needed something to go right, I was too tough on my kids, whether it was athletics or academics. I regret it, and I’ve told them it wasn’t fair to them. It had a big impact on my marriage. But every time I hit a tough spot, Leroy would pop into my brain cells. If you don’t step up and protect other people, who’s going to do it?”

The Colgate community got to hear Bill Lloyd ’80 share his saga on campus in January. He gave a public talk sponsored by the Robert A. Fox ’59 Management Leadership Skills Institute, moderated by classmate Lauren Ferrari ’80, managing director of the office of business integrity & compliance for Alcatel-Lucent. And students of the Rick Stone ’81 Business Ethics Seminar taught by Professor David McCabe discussed the case with Lloyd and Ferrari over dinner. They plan to continue the conversation at their 35th Reunion in May.

The Colgate community got to hear Bill Lloyd ’80 share his saga on campus in January. He gave a public talk sponsored by the Robert A. Fox ’59 Management Leadership Skills Institute, moderated by classmate Lauren Ferrari ’80, managing director of the office of business integrity & compliance for Alcatel-Lucent. And students of the Rick Stone ’81 Business Ethics Seminar taught by Professor David McCabe discussed the case with Lloyd and Ferrari over dinner. They plan to continue the conversation at their 35th Reunion in May.

Watch a video from Lloyd’s time on campus

A well written article and an important story to be told. It is great to see Colgate alumni taking a stand for business ethics. Special admiration for Bill Lloyd’s courage too. Thanks Colgate Scene for being a voice for this story.