New books of all kinds regularly roll into our office. No surprise: there are a lot of great writers among our alumni. And, maybe partly because of the setting of our campus — rural, and yet a center of learning and exposure to ideas and culture the world over — Colgate alumni also know the power a particular place can have, in life, learning, and literature.

As Eudora Welty, fiction luminary of the American South, put it, “Place, to the writer at work, is seen in a frame. Not an empty frame, a brimming one. Point of view is a sort of burning-glass, a product of personal experience and time; it is burnished with feelings and sensibilities, charged from moment to moment with the sun-points of imagination.”

Recently, we noticed a particularly strong sense of place — and displacement — in several works of new fiction by Colgate alumni. (As it happened, the lineup for this fall’s Living Writers course also reflects a global iteration of that theme.)

In light of that interesting confluence, we share selections from several of those alumni books, along with thoughts from the authors about how real places inspire the mind’s eye of the storyteller.

— Rebecca Costello

The River’s Tale

Michael Virtanen ’75

Lost Pond Press

In the opening passage of “The Waste Land,” T.S. Eliot wrote, in the voice of an elderly woman recalling an outing from her youth in the Bavarian Alps, “In the mountains, there you feel free.” It’s the wistful note from the modernist masterpiece about discordant civilization, which Professor Joseph Slater deconstructed and read to us in his elegant cadence in London. In other mountains, the Adirondacks, I’ve felt that without irony, on its gray cliffs, clear rivers, and approaching unbroken snow in deep forests — and then in the company of people who found there new or stronger or forgotten versions of themselves.

Alison slept on the ride north. She woke to an empty pickup and panicked for a moment until she realized they were parked outside the general store in Newcomb, which hadn’t changed in 12 years. Lottie came out with a bag of groceries, followed by the dogs. They walked down the road and loaded everything in Lottie’s little aluminum boat with the outboard motor, which she’d left tied to a post near the boat ramp. As they traveled down the Hudson, Alison sat toward the middle, behind the dogs, and later could hardly remember the trip. When they got off the river, the dogs ran ahead. She and Lottie pulled the outboard into the edge of the woods and chained it to a tree.

“If somebody tries to steal it I’ll chop their hands off,” Lottie said.”

“If somebody tries to steal it I’ll chop their hands off,” Lottie said. Alison wondered if she was joking and decided she was. Mostly.

There was an old aluminum canoe nearby, chained to nothing. The cabin stood about a hundred yards from the river, in a small clearing behind some trees. It had an open southern exposure with a big latticed window but sat snug against a stand of maple and birch on the north side. There was a plank porch, where Lottie, an ornithologist, worked at her typewriter when it was warm and sunny, with journals, photographs, and books on a table next to her. When it was cold or rainy, she worked indoors by the wood stove. The cabin had two rooms, a well for water, indoor plumbing, and a propane hot-water tank.

Alison had a slight cough and felt chilled and feverish. Lottie put her in the smaller room, the bedroom, on the soft mattress in a sleeping bag, under quilts. She slept there with the dogs snuggled against her as if they sensed her need for comfort and protection. She woke 12 hours later, damp and still tired. Lottie fed her vegetable soup and freshly baked crusty bread. Alison stayed in bed for another day, refusing to think about anything. When unsettling thoughts intruded, she went back to sleep. She found comfort in breathing the clean air, listening to the breeze in the trees, and hearing her aunt’s occasional footfalls. Her fever broke.

On the third day, she woke to the smell of breakfast. Lottie made pancakes, bacon, and stronger-than-usual coffee and laid everything out on the hewn wooden table. Alison looked around, at the log walls, the wood stove, the steel sink, and the window with the view of the forest, at Lottie’s clear blue eyes and lined face. Little had changed since her summers here. She saw her old recurve bow leaning against one of the two straight-back chairs.

AuthorSpeak

As a writer, how do you create a place for the reader who hasn’t been there?

“My bow,” Alison said. “I wondered what happened to her.”

“So that thing is a her. I remember.”

Alison ran her hands over its smooth contours. The string dangled from one end.

“Do you think the string is still good?”

“I bought that one the other day,” Lottie said. “It works just fine.”

Alison pulled the top of the bow down, attached the string at the other tip, and let it stretch taut. She felt the heft, ran her finger down the string, gripped the bow, and pulled the string back with three fingers until she could feel the 35 pounds of pressure on her fingertips.

“Where have you been?”

Her aunt had given it to her and taught her archery as a girl. She took it with her when she went exploring in the forest. She had small sharp field points on her arrows, instead of the large, lethal broadhead. In Lottie’s view, the field points were safer for everyone and probably still enough to drive off a bear, a man, or anything else. Alison had aimed the bow at various animals, after waiting furtively in her makeshift blinds, but she shot only one. She had heard a ruckus in a tree and saw something that at first she couldn’t believe, a squirrel on a high branch, biting a mourning dove, which was frantically flapping its wings. A strange and terrible sight to the girl. “Stop it,” she yelled. Then she drew an arrow and took steady aim at the squirrel’s thick body. The bird dropped off the branch, fluttered to earth, hopped a while, and flew off. The squirrel fell to the ground and died. Alison buried the squirrel and the arrow. “It’s your own fault,” she said by way of eulogy. She put the bow away. It was almost September anyway. Although she liked the idea of hunting, she realized she didn’t like killing things. She still felt that way.

“I figured it’s time you got out a little bit,” Lottie said. “I got you six arrows. They’re used, but they’ll do.”

Taking burlap sacks piled in the closet, Alison made an effigy, with head, arms, legs, and torso cut and roughly stitched together.

When Alison went to bed that evening, she laid the unstrung bow on the floor beside her. The dogs again snuggled against her. Over the next few days, she did little else but sleep, eat, and observe the forest from the front porch. Then, feeling fully recovered, she woke one morning with an inspiration. Taking burlap sacks piled in the closet, Alison made an effigy, with head, arms, legs, and torso cut and roughly stitched together. She filled it with twigs and leaves, and on the outside she pinned a piece of paper on which she had scrawled one word in big letters: Will. She felt a little alarmed at her action, as if he would know what she was doing and find a way to pay her back.

“What are you making?” Lottie asked when it was nearly finished.

“A target.”

She studied her niece and the effigy. “Anybody you know?”

“He was my boyfriend,” Alison said. “He was nice for a while. But then he changed. He cheated on me, and he wouldn’t let me go. He refused to let me go. And then he became my stalker. That’s the word for it now.”

The Albany Times Union called Virtanen’s characters “well drawn — imperfect, complicated, and human.” A veteran journalist, he reports for the Associated Press, and has written on the Adirondacks in newspapers as well as Adirondack Life.

Swing

Philip Beard ’85

Dystel & Goderich

All of my books seem to end up being (at least in part) about going home. And although defining “setting” as a separate element might be a convenient way to talk about literature, I don’t think of it that way. Where my characters live or where they grew up is just as much a part of their makeup as what they believe and whom they love. It’s also an area where I get to be selfish. I can put my characters in those few places where I feel “a part” as opposed to “apart” (in this case, both Pittsburgh and a version of Hamilton, N.Y.), and know that my own love for those places will create weight and meaning for my characters as well.

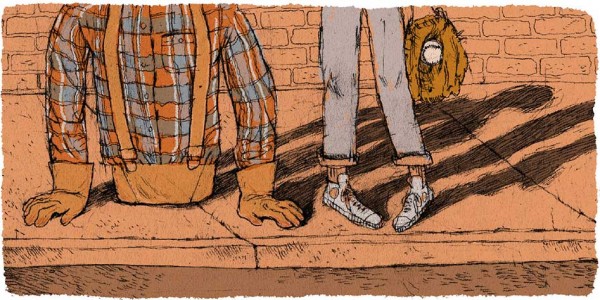

It is early October of 1971 and I am 11 years old, standing at a bus stop at the corner of Fort Duquesne Boulevard and Sixth Street in downtown Pittsburgh. I am there alone on a school day, without permission, which adds a sharpness to everything around me: the sidewalk sparkling blood-orange in the low sun; the light breeze cooling where it had warmed only an hour earlier; the bridges across the Allegheny River at Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth streets superimposed over one another in a maze of yellow iron. The Pirates, my Pirates, have just beaten the San Francisco Giants to advance to the World Series, and my father has just left us — two oppositely charged facts that make such a muddle of my thoughts that I don’t know whether to continue grinding the souvenir ball into the worn, oily palm of my glove, or throw them both into the river. My father left on a Saturday, carrying a single suitcase. On his way out, he put the Pirate tickets on the kitchen table and I sat on the window seat holding them, watching him walk to his car. My little sister, Ruthie, wrapped herself around his leg in the driveway and screamed. My older sister, Sam, pounded on the hood of his car, both hands clasped into one big fist, trying to make a dent. My mother stood unmoving in the doorway, resisting a visible urge to comfort her daughters in favor of letting my father’s departure become as ugly as possible for him.

Instead, the man next to me seems to have grown out of the sidewalk, with only his torso having emerged so far. He is hip-deep in the concrete and looks as though he has been there forever, waiting for a young King Arthur, me perhaps, to pull him free.

Thinking of my mother in that same doorway again, expecting me to get off the school activities bus, is the first time all afternoon that I have given any thought to how I am going to explain my absence. I had hung on the third-base railing for more than an hour after the final out to get my souvenir, so the crowd from the game is mostly gone. The few people approaching the bus stop are heading home from work or shopping: a slender, young black woman in a tailored white pantsuit holding her child’s hand; two businessmen carrying briefcases, laughing and talking about the upcoming Series with the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles; a fidgety, greasy-haired white man in an ill-fitting shirt and short, wide tie. All of them have come up Sixth Street from town, and that is the direction I am looking. It isn’t until I hear the sound of a bus approaching, with the whining downward shift of its gears, that I notice that someone has appeared next to me.

When I say “appeared,” I mean that quite literally. And I am momentarily bewildered by the fact that he doesn’t look as if he has finished appearing. Instead, the man next to me seems to have grown out of the sidewalk, with only his torso having emerged so far. He is hip-deep in the concrete and looks as though he has been there forever, waiting for a young King Arthur, me perhaps, to pull him free. He is a man; there is no doubting that, even though I am looking down at him. His hair is black and gray and mussed, wiry as a pot-scrubber, his nose wide and crooked, and there is a three- or four-day growth of salt and pepper beard on his face. Still, it isn’t until the bus comes to a stop in front of us and opens its doors that I understand what I am seeing — staring at, more precisely, in violation of every childhood admonition from my parents to do otherwise. The adults around me do no better, though. They all take an involuntary step backward, the young black woman pulling her child, and I am left standing alone with him.

AuthorSpeak

As a writer, how do you create a place for the reader who hasn’t been there?

“Thank you kindly,” the man says, as if everyone behind us has, in fact, remembered their manners. Then he winks at me. “You here all by yourself?”

“Yessir,” I reply, thinking I must be under some kind of spell to talk to a stranger and tell him I’m alone, a double-play of cardinal rules violations in the Graham household.

“You comin’ from the game?” He nods at my glove still clutching the ball.

“Yessir.”

“Lucky kid. What’s your name?”

“Henry.”

“Good baseball name. Like Hammerin Hank Aaron.” He cocks his head toward the bus.

“Mind if I go first?”

“Nosir.”

“Thanks.”

He does this two or three more times, all of us watching unabashedly, until he reaches the base of the bus steps.

He has no legs, barely even a hint of a thigh Strapped over broad, powerful shoulders, he wears leather suspenders attached to a thick leather harness that protects the base of his perfectly flat torso. Even concealed inside a flannel shirt it is clear that his arms are massive, and he wears heavy work gloves on huge hands, which he now places on the sidewalk in front of him. He presses, his shoulders shrugging downward, and in one smooth motion lifts his torso, swings it forward as if on a set of parallel bars, and sets it down again gently on the sidewalk. He does this two or three more times, all of us watching unabashedly, until he reaches the base of the bus steps. I feel the group around me tense, sure that the man has gone as far as he can go on his own, but equally unsure of how we are to help. He stops and looks up at the driver, who appears neither concerned nor surprised.

“Hey, Russ,” the half-man says.

“How you been, John?”

“Fine thanks. Hey, what did the bus driver say to the legless man at the bus stop?”

“I don’t know. What?”

“‘Hey there. How you gettin’ on?’”

The driver shakes his head. “Come on now. I got other customers.”

“I’m comin’,” he says. Then he places his hands firmly on the bottom step and lifts himself up as easily as I might have lifted myself out of a swimming pool. He takes the second step, then the third, then turns and swings himself down the aisle, out of sight.

“Come on, folks,” the bus driver beckons, because none of us has moved, and I am the first to break the dazed tableau and follow John Kostka, The Swinger, up and into the bus for home.

New York Times bestselling author Sarah Gruen called Swing, available from all major e-booksellers, “a novel to be savored.” An attorney as well as a writer, Beard reports that his first novel, Dear Zoe, is in development as a feature film.

Unmentionables

Laurie Loewenstein ’76

Kaylie Jones Books/Akashic Books

Unmentionables opens on a steamy August evening in 1917 as a small Illinois town gathers to hear Marian Elliot Adams, an Easterner and an activist who sweeps onto the stage seeking to enlighten and edify. To outsiders like Marian, the Midwest is a vast, uncultured swath that, as Nick Carraway observes in The Great Gatsby, is “the ragged edge of the universe.” To Midwesterners like myself, it is a place of great beauty; of distant horizons where the sky bleaches to white, where windbreaks of catalpas hem farm fields, where the courthouse is ornately fluted. But it is also a place of contradictions, where politeness and conformity glide above deep currents of emotion and sentiment. Where we are both insiders and outsiders — fertile ground in which to explore the true nature of community.

The breezes of Macomb County usually journeyed from the west, blowing past and moving quickly onward, for the county was just en route, not a final destination. On this particular night, the wind gusted inexplicably from the east, rushing over fields of bluestem grasses, which bent their seed heads like so many royal subjects. A queen on progress, the currents then traveled above farmhouses barely visible behind the tasseled corn, and swept down the deeply shaded streets of Emporia, where they finally reached the great tent, inflating the canvas walls with a transforming breath from the wider world.

The farm wives had staked out choice spots under the brown canvas; an area clear of poles but not far from the open flaps where they might feel the strong breeze that relieved the oppressiveness of the muggy August evening. The ladies occupied themselves with their knitting needles or watched the crew assembling music stands. Some fretted about sons, already drafted for the European trouble and awaiting assignment to cantonments scattered across the country. They pushed back thoughts of the steaming canning vats they faced when the weeklong Chautauqua assembly of 1917 concluded. All they would have to get through another dreary winter were the memories of the soprano’s gown of billowing chiffon; the lecturer’s edifying words; the orchestras and quartets.

The ladies occupied themselves with their knitting needles or watched the crew assembling music stands.

The strings of bare bulbs that swagged the pitched roof were suddenly switched on. The scattered greetings of “Howdy-do” and “Evening” grew steadily as the crowd gathered, burdened with seat cushions, palmetto fans, and white handkerchiefs. Leafing through the souvenir program, they scrutinized the head-and-shoulders photograph of the evening’s speaker, a handsome woman wearing a rope of pearls. She was described as a well-known author, advocate for wholesome living, and suffragist. What exactly was this lecture — “Barriers to the Betterment of Women” — about? Some expected a call for more female colleges, others for voting rights.

AuthorSpeak

As a writer, how do you create a place for the reader who hasn’t been there?

Then Marian Elliot Adams, a tall and striking woman in her early thirties, swept onto the stage. She wore a rippling striped silk caftan and red Moroccan sandals. With dark eyes and dramatically curved brows, her appearance hinted at the exotic.

In ringing tones, she announced, “I am here tonight to discuss the restrictive nature of women’s undergarments.”

Hundreds of heads snapped back. The murmurs of the crowd, the creaking of the wooden chairs, stopped abruptly. Even the bunting festooning the stage hung motionless, as if it had the breath knocked out of it.

“I am here tonight to discuss the restrictive nature of women’s undergarments.”

Marian’s gaze swept across the pinched faces, assessing the souls spread before her, and she concluded that they were the same people she’d been lecturing to for the past three months. There was the gaunt-cheeked elder with his chin propped on a cane; the matron with the bolster-shaped bosom; the banker type in a sack coat; the slouching clerk with dingy cuffs. Just like last night and the night before that, stretching back eighty-three straight nights — these strangers she knew so well.

Kirkus Reviews called Unmentionables an “engaging first work from a writer of evident ability.” A fifth-generation Midwesterner, Loewenstein has been a feature and obituary writer for several newspapers and a college writing tutor.

Snow in May

Kseniya Melnik ’04

Henry Holt and Company

Although the linked stories in Snow in May are set in various places, the book’s emotional center of gravity is Magadan, my isolated hometown in the northeast of Russia. Nothing excites my literary imagination more than location — the physical place with its specific political situation, landscape, quality of light, and level of noise. Magadan, with its dark history as a gateway to one of the cruelest networks of Gulag camps but also a source of my happy childhood memories and much family lore, was a place too intriguing for me to resist. An element of longing for a place I’ve left comes into play, too. I wanted to portray my hometown in all its complexity, including the years of relative prosperity.

In “Rumba,” set during the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, a middle-aged ballroom dance teacher, Roman Ivanovich, nurtures the exceptional talent of his 12-year-old student, a girl he nicknames Asik, which leads to admiration of a different kind. By this point in the story, Roman Ivanovich oscillates between looking at Asik through her various dance roles and seeing her as just a young girl from a broken family, for whom, perhaps, he has more responsibility than he first thought.

On his way back from the grocery store he lingered in a small park with a worn-out bust of Berzin, the first director of the Dalstroy trust and forced-labor camps in Kolyma. Naked trees stuck out of the tall banks of hardened snow. Theatrically fat snowflakes streamed from the black sky. It was quiet. The cold air smelled of burning garbage — his childhood’s scent of freedom and adventure, when he and his gang of ruffians would run through courtyards and set trash containers on fire to the grief of hungry seagulls. Before his mother bound his feet in dance shoes and shackled him to a girl.

Theatrically fat snowflakes streamed from the black sky. It was quiet. The cold air smelled of burning garbage — his childhood’s scent of freedom and adventure…

He had a sudden craving for fried eggs with a particular Polish brand of cured ham, sold at a private shop in the town’s center. It was his one evening off work; he figured he deserved a small indulgence.

He walked up Lenin Street. Its preholiday luminescence was even more radiant this year, more drunkenly optimistic. White lights lay tangled in trees. A shimmering canopy of pink garlands hung across the roadway. Up ahead, the dystrophic A of the TV tower, the Eiffel Tower’s long-lost illegitimate child, shyly illumed its red and white stripes. The town clock, lit up in green, read half-past eight. By now the junior group would be halfway through their weekly ballet class.

AuthorSpeak

As a writer, how do you create a place for the reader who hasn’t been there?

These classes weren’t mandatory, but Roman Ivanovich had made it clear that no dancer should dream of correct posture without paying their dues at the barre. He considered the instructor, Gennady Samuilovich, too lenient, though, and preferred not to imagine the likely chaos of his practices.

The wind had picked up. He bought the Polish ham and walked, out of habit, to the Palace of ProfUnions. He crept around the back and hid in the shadow of a copse.

Through a single window Roman could see the ballet class. The vision, suspended in the darkness, seemed to him all the more brilliant and distant. Against his expectations, most of the junior group was at the barre by the mirrored wall, diligently knocking out petits battements. Gennady Samuilovich strode back and forth, whipping the air with his wrists. His white tights showcased the anatomy of his legs in excessive detail.

Pale Asik, dressed in a black leotard, with her hair up in a tidy bun, was merely adequate. Her butt kept sliding out of alignment, and she wobbled as her leg swung.

Pale Asik, dressed in a black leotard, with her hair up in a tidy bun, was merely adequate. Her butt kept sliding out of alignment, and she wobbled as her leg swung. But she was trying the hardest of them all. Roman Ivanovich was in shock. Who would she be now? Not his Carmenochka, not his fiery little gypsy. He watched her till the end of class. She was that hard-working average student he liked to praise to the parents. Effort over results. He breathed easier.

Gennady Samuilovich dismissed the class. Before wandering off, several girls — Olesya among them — trapped Asik in choreographed parentheses. They were saying something to her, something unpleasant, judging from Asik’s pinched mouth. She crossed her arms and threw her weight to one hip. After they left, Asik was alone in the room. She turned to the mirror and performed an ironic half plié, half curtsey to her reflection. Then she put her elbows on the barre and worked her face through a series of smiles in different tonalities. A laughable sinner-seductress. Pierrot at a party. Piranha. She stomped — sloppily, neurotically — pitched forward and folded herself at the waist over the barre (against the rules! The barre wasn’t made to sustain such weight), her leotarded backside the shape of a black heart. She closed her eyes and just hung there, like a piece of laundry forgotten in the courtyard.

Roman Ivanovich imagined the fragile basket of her hip bones rubbing painfully against the barre, all her little organs squished. He looked down. The snow was mildewing over a pile of cigarette butts and a green balloon scrap still attached to a string. She was nothing more than a body that danced.

At press time, Snow in May had just made the short list for the International Dylan Thomas Prize. Melnik’s work has been published in Virginia Quarterly Review and selected for Granta’s New Voices series.

The Tumble Inn

William Loizeaux ’76

Syracuse University Press

Mark and Fran Finley, two high school teachers tired of their jobs and discouraged by their failed attempts at conceiving a child, abruptly move from New Jersey to become innkeepers on a secluded lake in the Adirondacks. Why did I take them there? Well, having spent many summers in the Adirondacks with my family, I have some knowledge of that part of the world. But more importantly, those old mountains, forests, and lakes are, for me, a metaphorical landscape: a place of extremes, of extraordinary beauty and extraordinary danger, and a place where the usual boundaries between those extremes are often vague, difficult to read, or sometimes nonexistent. So easily, so seductively, one can slide from beauty into danger. Peering over the domed granite at the top of a waterfall, you take a little step to see more of the cataract below, and then you take another step, and another, and then…. So if you’re a novelist, what better place to plunk down your protagonists and give them challenges and difficult choices? In the passage below, Mark, who narrates the story, recalls the budding relationship between the now-teenage daughter he and Fran finally conceived, and the son of visitors to the inn.

“Nobody,” of course, turned out to be somebody. Or somebodies. And one of those somebodies during that late summer after Nat’s junior year was a guy named Chuck Frazier, the son of Ted and Clara Frazier, who were longtime Regulars, though this would be their last time here, as they were coming up in the world and would soon go on fancier vacations. A few summers before, Chuck had been “Charlie,” just another spindly, curly-headed kid who ran on the beach and threw a Frisbee for hours. Now he was tall, had ropey muscles, a deep tan, stubble on his face, and hair under his arms, and his curls had grown into long, blonde waves that put you in mind of surfers. When he was wearing any sort of shirt at all, he wore a blue college sweatshirt. He also wore a backwards baseball cap that said “Just Do It!” and he walked in a cocky, loose-jointed way that made you wonder how his baggy swimming shorts ever stayed on his narrow hips. He must have been at least 18 because, during the two weeks his family was here on vacation, he drove his parents’ new silver BMW, churning in and out of the driveway, spitting stones, and churning Fran’s and my insides, as well. He’d always been a fun-loving, daredevil kid with an infectious smile, who in his early teens had learned how to slalom water ski, how to lean way back, carving through the water at breakneck speed, once wearing one of his father’s red business ties, and to tell the truth, I’d always liked him, though things would get more complicated.

I don’t know exactly when he and Nat first caught each other’s eye as blossoming teenagers, but that August you couldn’t help but feel the attraction, like a charge in the air. He was just so hungry, self-assured, and handsome in his lean and casual way. And she was just so curious, eager, ready and not ready for anything.

What boundaries there are you can wriggle around, and so much is unrestricted or indefinite. You won’t find many fences or walls around here.

During his initial days here that summer, he and Nat would loosely drift around one another, he, in his sweatshirt, hanging around the inn, suddenly interested in the landscape photos on the living room walls or the contents of the bookshelves. Or she, in her jeans, flip-flops, and tank top — and suddenly interested in things automotive — would wander over to the parking lot, where he’d be fiddling with that car, bent over the engine or waxing the hood, a sheen of sweat on his back and shoulders.

As advised, Fran and I tried to set boundaries. We said that Nat had to be in every night by ten. We said that under no circumstances could she go out driving with Chuck behind the wheel. So cleverly, in the evenings, they’d sit for hours, low down in the front seats of that BMW, parked in the back corner of the lot. I guess that’s the thing about living in the wilderness. What boundaries there are you can wriggle around, and so much is unrestricted or indefinite. You won’t find many fences or walls around here. We seldom speak of property as “lots.” One thing blends into another. By degrees, a gravel road becomes a dirt road, which narrows down to an old wagon track, which becomes a foot trail, which peters out into a deer path overhung with foliage … and then you’re just into the thick of it, “bushwhacking.”

AuthorSpeak – Bill Loizeaux

As a writer, how do you create a place for the reader who hasn’t been there?

Over the next week, we saw less and less of Nat. With Chuck, she was always down on the beach, or out somewhere on a long walk, or transfixed by the beauty of a V-8, 324-horsepower engine. When she was here, she was usually “busy” in her room, with her music going behind her closed door late into the night. In the mornings, she slept later and later, often missing breakfast altogether. When occasionally she couldn’t avoid us, she was certainly uninterested in our interest in and concern for her. “Back off!” she said. In the kitchen, she’d leave a carton of ice cream on the stove top and put silverware away in the refrigerator. Once I saw her rinsing the same coffee cup for minutes on end, and she jumped when, without meaning to, I disturbed her. Her whole being was elsewhere.

Then on the night before the Saturday when Chuck and his parents were to leave, she didn’t come home by ten. Nor by ten-thirty, when Fran and I usually said goodnight to the guests remaining in the living room and headed up to bed. Nor even by eleven. Nor had she called from wherever she was to say she was late. Sheepishly, we knocked on the Fraziers’ door and asked Ted and Clara if they knew of Chuck’s whereabouts. We said he “might” be out somewhere with Nat.

Older, and perhaps because he was a guy, Chuck was on a looser leash than she. “Oh, if they’re out somewhere, they’ll turn up soon,” Ted said offhandedly. “Kids,” he added by way of explanation, which, for Fran and me, wasn’t explanation enough.

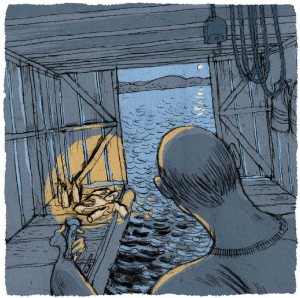

So I took the flashlight outside where the wind was kicking up. Near the parking lot, I cringed with visions of what I might see or interrupt. Did I really want to find them? No. But not finding them would be even worse.

There in the back corner was the BMW, crouching on its wide tires, but no one was inside. I went down to the beach and shined the flashlight across the sand, all bumped and dented with footprints. Here and there, I saw a plastic shovel or a castle some kids had made. Canoes lay upside down, like strange, misplaced bananas. On the far end of the beach, a small campfire danced in the wind and darkness, and, walking over, I said a few words to the circle of folks who were just breaking up before heading to the inn for bed. None of them had seen Nat or Chuck that evening. Retracing my steps, I shined the flashlight on the shaggy field where the tall grasses were swaying and thrashing. I turned off the light and for a while stood still and listened. I heard waves breaking on the beach, and people laughing and saying goodnight, after they’d doused the campfire. It was one of those times when a cool westerly wind carries the smell of the lake mixed with pine and that sudden sense that these late summer nights are so few and fleeting, going, almost gone, as you live them.

I turned the flashlight back on and, following some intuition, crossed the sand toward the boathouse, a dark, peaked, boxy shape, with its hip roof overhanging much of the dock that extends a good ways into the water.

I turned the flashlight back on and, following some intuition, crossed the sand toward the boathouse, a dark, peaked, boxy shape, with its hip roof overhanging much of the dock that extends a good ways into the water. I went up the granite step to the paint-chipped back door, then lifted the latch and followed the beam of my flashlight inside. The air in the boathouse smelled of waterlogged wood and the muddy nests of barn swallows. To my left were the empty canoe racks and the warped stairs that lead through a trap door to the storage attic above, which was still padlocked. No, they couldn’t be up here. Straight ahead, ropes and pulleys hung from beams. To my right and attached to a thick post was the winch for hauling up the guide-boat for the winter. There were the life jackets hanging from pegs on the wall. There on the narrow dock were the horn-shaped cleats to which the boat should have been tied. But the bay between the docks was empty, and near the middle of one dock lay Nat’s flip-flops and Chuck’s blue sweatshirt in a heap, alongside four empty beer bottles.

The Tumble Inn is Loizeaux’s first novel for adults; his memoir Anna: A Daughter’s Life, was a New York Times Notable Book. He’s a writer-in-residence in Boston University’s English department.

The Geography of You and Me

Jennifer E. Smith ’03

Poppy/Little, Brown and Company

I’ve lived in New York City for nearly a decade now, and have been lucky enough to experience a lot of memorable moments here. But even all these years later, the Northeast blackout of 2003 still stands out most of all. My experience that night didn’t quite unfold the way it does in the book — for one thing, I didn’t find myself trapped in an elevator with a cute boy! — but the magical, almost celebratory atmosphere of the city was the same. It was a hot summer night, and everyone seemed to be out in the streets. Ice cream shops were giving away free cones before they could melt, and restaurants were serving food by candlelight; people were hanging out of their windows, waving at all the commuters on their long walk home. There was a sense of camaraderie that really struck me. I was brand-new to New York then, and I had no idea at the start of that day how much I’d come to love the city by the end of it. Ten years later, I still do.

When he unlocked the door, they stumbled out onto the darkened roof, their eyes focused on the ground as they picked their way across the tar-covered surface.

“Over there,” Owen said, pointing at the southwest corner, and Lucy walked over to the ledge that ran along the perimeter, where she stood looking out.

“Wow,” she breathed, rising onto her tiptoes. Owen dropped the backpack before joining her, positioning himself a few inches away. The wind lifted her hair from her shoulders, and he caught the scent of something sweet; it smelled like flowers, like springtime, and it made him a little dizzy.

They were quiet as they took in the unfamiliar view, the island that was usually lit up like a Christmas tree now nothing but shadows. The skyscrapers were silhouettes against a sky the color of a bruise, and only the spotlight from a single helicopter swung back and forth like a pendulum as it drifted across the skyline.

Together, they leaned against the granite wall, invisible souls in an invisible city, peering down over forty-two stories of sheer height and breathless altitude.“I can’t believe I’ve never been up here,” she murmured without taking her eyes off the ghostly buildings. “I always say the best way to see the city is from the ground up, but this place is amazing. It’s–”

“I always say the best way to see the city is from the ground up, but this place is amazing.”

“A million miles above the rest of the world,” he said, shifting to face her more fully.

“A million miles away from the world,” she said. “Which is even better.”

“You’re definitely living in the wrong city, then.”

“Not really,” she said, shaking her head. “There are so many ways to be alone here, even when you’re surrounded by this many people.”

Owen frowned. “Sounds lonely.”

She turned to him with a smile, but there was something steely about it. “There’s a difference between loneliness and solitude.”

Susanne Colasanti, bestselling author of When It Happens, said Smith “represents the absolute best in young adult writing.” Author of six novels, Smith is also a senior editor at Ballantine/Random House.