When you go to the movies these days, your feature film is always preceded by previews for other upcoming motion pictures. But back in the heyday of silent films, moviegoers arrived early in order to catch a live theatrical preview of the very film they were about to see. Called prologues, these elaborately staged productions conveyed the atmosphere, plot and even the sensory experience of the story that was about to unfold on the silver screen for audiences still adapting to the novel new media of movies.

Mary Simonson, associate professor of film and media studies and women’s studies, became captivated by these prologues of motion pictures past that have vanished from our collective cultural memory. She captures their grandeur and illuminates their importance in her paper, “Adding to the Pictures: The American Film Prologue in the 1920s,” which was published in the spring 2019 issue of American Music.

Mary Simonson, Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies and Women’s Studies

As a musicologist, Simonson studies the ways that music works in multimedia performance across different genres. “I’m particularly interested in moments where recorded media meet live media,” she says. She came across the concept of prologues while researching the golden age of silent films in recently digitized archives of film trade journals from the 1920s. “I kept seeing this term ‘prologue’ without any explanation,” she says. “It took me several months to even figure out what the writers meant. It was sort of assumed knowledge in the 1920s. But as soon as I deciphered it, I became hooked and fascinated by the whole phenomenon.”

Prologues broadly fell into two categories. In action prologues, actors performed highlights of the film to follow, their dialogue often drawn from the exact intertitles that would appear on the screen. “What was shocking to me is that they very often staged the climactic scene of the movie,” she says. “They were actually giving a spoiler of the film.”

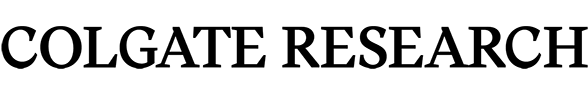

Atmospheric prologues oriented viewers to the time, place, and characters of the film in a less direct, more multisensory fashion. For example, if a film was set in the Middle East, exhibitors might diffuse incense or jasmine into the theater air-conditioning system and hang beaded curtains on stage. The actors on stage might portray allegorical characters related to themes of the film rather than the starring characters of the film itself. Musical selections would reflect the film’s setting. For example, the 1921 movie Passion tells the story of a love triangle set in Paris. A prologue created for the film by the Strand Theater in Brooklyn featured the theater orchestra playing the “Robespierre Overture” as well as an interpolation of “La Marseillaise.”

Photo of the prologue to Passion (dir. Lubitsch, 1920), staged at the Strand Theater in Brooklyn, as reproduced in Exhibitors Herald, January 29, 1921.

Her struggle to simply define prologues was merely the first of many challenges Simonson encountered in researching the subject. “Prologues weren’t recorded in any way,” she says. “There weren’t any surviving scripts. They were live performances that were unique to each theater. There would have been thousands and thousands of them performed, so to even make generalizations about them took a lot of work.”

What she found, in general, was that prologues were extremely popular. “Patrons would call the theater to find out when the prologue started so they would make sure they didn’t miss it,” she says. Since many movie theaters were converted opera houses, the existing stage and proscenium provided the ideal infrastructure for prologues, which often featured songs, dances, and elaborate sets. For example, for its prologue for the 1921 film The Devil, the Strand Theater in Manhattan borrowed the original film sets from the studio and hired dancers who had appeared in the film.

However, that particular production was an outlier. Most prologues were strictly local productions, featuring local performers and catered the material to the cultural sensibilities of the home audience. Still, even these homegrown productions had high aspirations.

“Exhibitors were eager for film to be perceived as legitimate entertainment, much like theater or art music,” Simonson says. “They wanted to attract upper-class patrons as well as members of the working class. There was an idea that by integrating more live performance and ‘better’ music – by which they usually meant Western classical music – into the prologues, it was more likely that a range of patrons would be drawn to film theaters.”

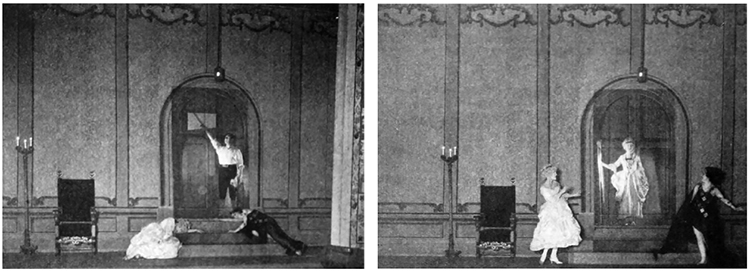

Photo of the prologue for Last of the Mohicans (dir. Brown and Tourneur, 1920), staged at the Strand Theater in Brooklyn, as reproduced in Motion Picture News, January 22, 1921.

The sonic landscape created by a prologue’s music and dialogue was the crux of Simonson’s research. For the experience of watching a silent film was anything but silent. “The prologue introduces a whole soundscape for the film even before the film starts,” she explains. “Even though the dialogue of the characters is reduced to intertitles within the film, it’s easy to imagine that the audience members would be hearing in their heads the voices that had just performed those lines live in the theater.”

Simonson sees prologues as emblematic of the drive by theater exhibitors and film studios to make films an immersive experience. “There were all these developments at that time, such as making sure the theater is dark so that your attention is focused on the screen,” she says. “A prologue’s soundscape deepens that immersion and helps the audience feel like what they’re seeing in the film is multisensory in the same way it would be for any other live performance.”

Although prologues vanished along with silent films, Simonson still hears their echo in modern movie theaters, with their Dolby Digital Surround Sound, IMAX screens and RealD 3D. “Even though the technologies are new,” she says, “the impulse behind them is not much different than what was inspiring movie exhibitors in the 1920s: to create a rich multisensory experience.”