For scholars of American history, the second half of the 19th century has traditionally included two significant but separate story lines: the Civil War and westward expansion. The former has most often been framed as a battle fought in eastern and southern states over the future of slavery. The latter has focused on the armed conflicts between western Native nations and the U.S. military, known collectively as the Indian Wars, which raged after the Civil War had ended. But as historian Ryan Hall argues, it’s time we looked at the devastating effects on the American West that the Civil War unleashed as it was unfolding.

Hall, assistant professor of Native American studies and history, is an expert on the North American West. In the process of doing research for his 2020 book Beneath the Backbone of the World: Blackfoot People and the North American Borderlands, 1720-1877, he was surprised to note that the four years of the Civil War coincided with profound disruptions for the Indigenous people of the northern Great Plains. In a recent article, he focuses on the upper Missouri River Valley, where those disruptions would prove ruinous to Native people by destabilizing their communities and hastening the conquest and dispossession of their lands. But the culprits in this case weren’t bloodthirsty soldiers or overzealous generals. They were, for the most part, bureaucrats working for the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) and the civilian entrepreneurs they engaged.

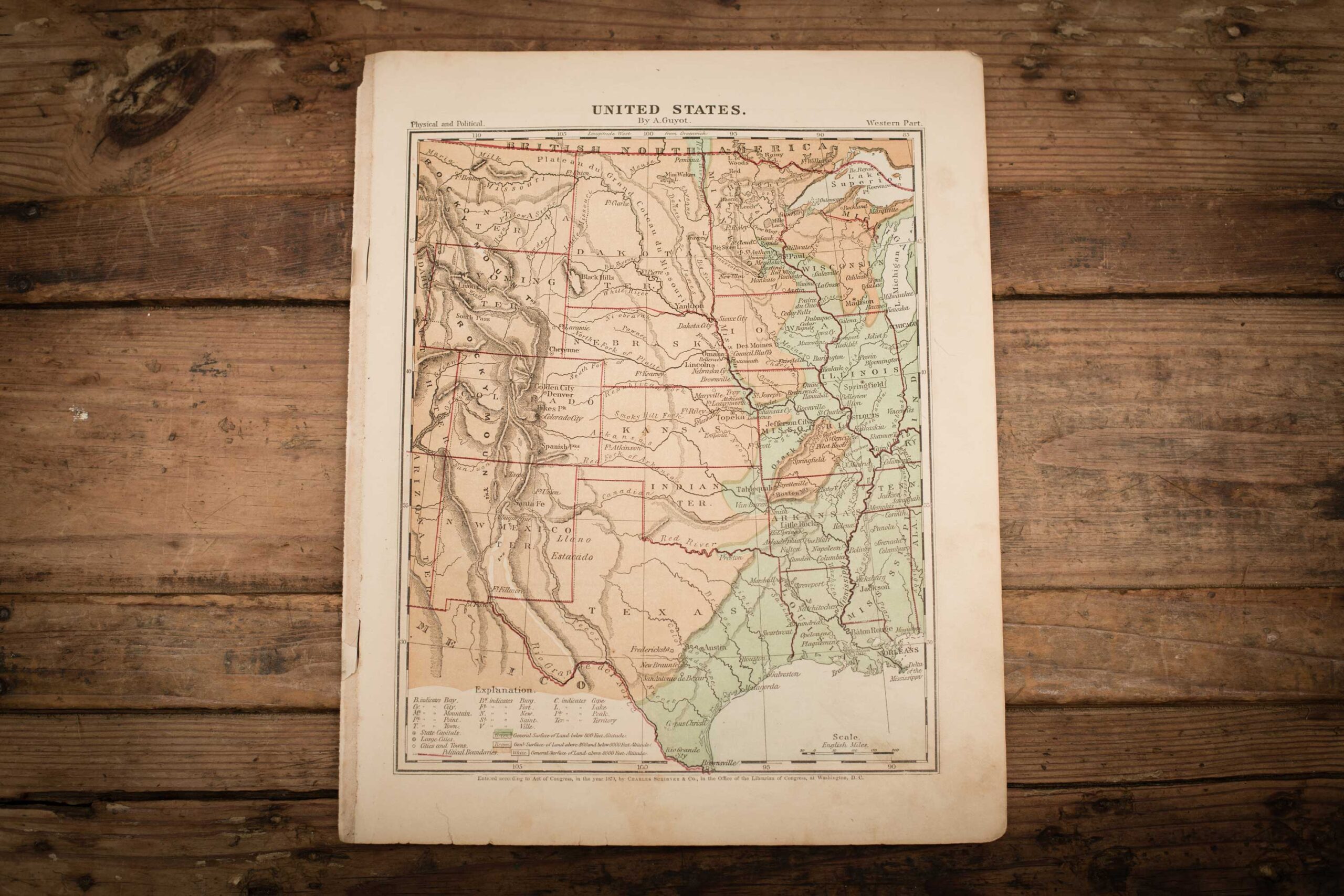

Focusing exclusively on the Indian Wars distorts our understanding of Native American history, Hall says. Before 1861, about half of the land area of the United States was still Indigenous land: “Native people weren’t subjugated. They weren’t on reservations. They were still an extremely powerful force in the [western] part of the continent.” The overwhelming majority of them rarely interacted with, much less fought, the U.S. military. “But every tribal nation,” he says, “dealt with the Office of Indian Affairs.”

Until the Civil War, the relative stability of the relationship between the U.S. government and the western nations — Lakota, Crow, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, and many others — rested on two important pillars: the fur trade and treaties. The fur trade consisted of isolated outposts along the Missouri River where Native people exchanged bison robes and other pelts for arms, ammunition, and manufactured goods. The treaties were not peace treaties, but rather diplomatic agreements whereby Indigenous nations facilitated westward expansion by newcomers — settlers, explorers, prospectors, and the like — by maintaining peace among themselves and by not interfering with the building of infrastructure, such as roads; significantly, they also retained control of their lands. In return, they received annual payments of money and supplies.

According to Hall, the turmoil of the Civil War years in the East “rippled west” and toppled those pillars of stability. Wartime inflation decimated the market for fur, and many of the fur companies that had traded in Native products closed. Worse, perhaps, Lincoln’s new, Republican administration replaced existing OIA agents, many of whom had been performing their duties more or less appropriately and had forged relationships with Native leaders, with opportunistic individuals whose appointments were based not on competence or integrity, but on personal or political connections. The actions of these “unqualified men,” as Hall describes them, ranged from lamentable to “sickening.” Some simply didn’t report to their posts. Many diverted the annuities (disastrously shrunken by inflation) promised in the treaties, and which had become crucial to Native people’s survival, to white settlers. Others deliberately undermined starving Native nations by supplying them with rotting offal and other spoiled goods. Through neglect, fraud, and savagery, these bureaucrats inflicted catastrophic harm.

One man stands out to Hall as a particularly vivid and shocking embodiment of bureaucratic degeneracy. In 1861 Walter Burleigh, a physician from Pennsylvania, was appointed to the Yankton Agency, where he pilfered goods and money meant for the Yankton. He had the OIA underwrite a school he never built, more than a thousand meals for students who didn’t exist, and salaries for “teachers” who were, in fact, members of his and his friend’s families. He was investigated but never punished, and while the Yankton nearly starved to death, Burleigh was elected to an even higher post after the war. Worst of all, according to Hall, Burleigh subsequently bragged about his actions, one of many striking examples of the dehumanization of Native people by white colonial settlers.

“The Civil War was a tipping point for Native people of the West,” Hall says. “All the things they relied upon to maintain peace with the United States fell apart. And so, after the Civil War, when there was this huge push for Western expansion, Native people were in a destabilized and desperate position.” In this ravaged landscape, American empire building could proceed.

Hall, currently at work on his second book, which will focus on abuses and corruption in the Office of Indian Affairs, considers westward expansionist colonialism, or “westering,” as the defining feature of the history of the United States. “You see all things differently if you put Indigenous land at the center of the story and look outward from there,” he says.

Which is why in his Native American History survey course, Hall always has his students (very few of whom are Native) write the Indigenous history of their hometown: “Every place in the United States was and is an Indigenous place, and there is some point in history when Indigenous people were dispossessed of that land.” For his students, seeing themselves as part of that history, Hall says, is a “profound experience.”