We expect countries to share false information with enemies — but why would they do that to their allies?

In the spring of 1941, Great Britain was facing desperate circumstances. Nazi Germany had occupied France and inflicted heavy bombing damage on London; now it was driving into North Africa. Yet, despite prior promises of aid, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sending mixed messages to his British compatriot Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Though the United States passed a law authorizing military support for the Allies, it failed to declare war on Germany as expected and had recently reneged on promises to escort British ships.

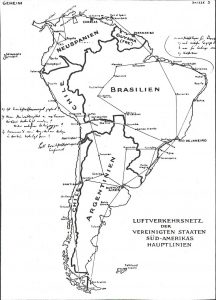

Churchill decided that the Americans needed a little convincing and authorized his intelligence agencies to share a Nazi letter and map outlining a planned invasion of Central and South America. Those documents eventually spurred Roosevelt to give a powerful speech detailing a “secret map made in Germany [that] makes clear the Nazi design not only against South America but against the United States” and asking Congress to repeal the Neutrality Act. There was only one problem: the letter and map were both fake.

“They created false intelligence and then shared it, not just with their enemies, which is kind of the natural target, but instead they shared it with their friends,” says Danielle Lupton, assistant professor of political science. In the high-stakes world of international spycraft, countries often create false information to throw enemies off the scent. Less well-known, however, are efforts that intentionally mislead allies using expertly produced fake intelligence.

In a recent journal article, published with Jonathan Brown of Sam Houston State University and Alex Farrington of the University of Oregon in the Journal of Global Security Studies, Lupton explores why countries may want to intentionally fool their friends — and why the recipients of information buy it so readily. “It’s a really important question, because we make the assumption that these positive and friendly alliance relationships will always engage in honest, good, well-meaning behavior,” Lupton says. “And yet, we have key instances where they’ve purposely been deceptive to each other.”

In order to explain this phenomenon, the researchers examined a trove of declassified documents in both American and British archives. From the outset, they drew from research by Brown, Farrington, Lupton, and others on social psychology, speculating that personal relationships were key in the sharing and acceptance of the false information. “A majority of scholarship on intelligence-sharing relationships deals with more structural factors, such as bureaucratic politics or relative power capabilities,” Lupton says. “But we have a lot of evidence showing that individuals matter.”

Once you have established these positive relationships, you want to treat those with care.

In the World War II case, not only had Churchill developed a personal relationship with Roosevelt dating from before Churchill became prime minister, but key underlings in the countries’ spy agencies had also created interpersonal ties that facilitated communication. While these personal relationships generated greater trust between the two sides, it also posed a danger that individuals might be misled, something psychologists call the “paradox of trust.”

“These positive relationships establish a pattern of behavior where you start to think, okay, these people are going to be on my side,” Lupton explains. On the other hand, when one side betrays that trust — as Roosevelt did by failing to declare war or escort ships as Churchill expected him to do — it can cause the other side to respond in kind. “It sends a really negative signal to the other side,” Lupton says.

Thus, Britain had both the incentive to create false information to get back at the Americans for their breach of trust, as well as the reservoir of trust to get the Americans to believe it. Critically, Britain’s intelligence capabilities were stronger than those of the United States, so the Americans weren’t able to verify the information independently, choosing instead to rely on British sources. “It actually didn’t come out until many years later that it was totally fake,” Lupton says.

In examining the case, Lupton and her colleagues found previously unexplored documents showing that Roosevelt and other American officials took the intelligence seriously and took specific actions based on it, for example establishing military cooperation agreement with Bolivia. By December 1941, of course, Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor, causing the United States to enter the war on the side of the allies, so it’s hard to tell exactly how the fake intelligence might have otherwise affected the American intent to declare war.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Royal Navy aide, and Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill on deck of HMS Prince of Wales during Atlantic Charter conversations. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, National Archives

The case, however, demonstrates importance of the old adage “trust but verify” — that is, intelligence agencies should be vigilant to independently verify information, rather than rely solely on the say-so of allies. But another implication is understanding the significance of trust in the first place. Churchill’s actions are understandable in the light of the terrifying threat the country faced from Nazi Germany, but it was America’s failure to follow through with its promises, both implicit and explicit, that spurred him to dishonesty.

That’s something the United States would do well to remember, says Lupton, as it pursues sudden policies on trade or international alliances that could alienate its friends. “Once you have established these positive relationships, you want to treat those with care,” Lupton says. “You need to recognize how your rhetoric and actions are perceived by friends and allies — and how your allies can respond in ways to protect themselves in the long term.”