Preface

Colgate’s approaching bicentennial provides an ideal moment to engage in many discussions about the university — looking at its history, its future, and its mission. I was intrigued when President Brian Casey invited me to join a communitywide discussion about Colgate’s campus rituals. He indicated that he believed deeply in the power of ritual and beauty to connect a community, to remind an institution of its past, and to invite all students, faculty, and alumni to think about its future. President Casey was also responding to questions raised on campus through the years about the nature of the Torchlight Ceremony.

President Casey reached out to me because public art, civic engagement, human rights, public service, and community ritual have been my passions for 30 years. I have explored them around the world in my teaching and by helping communities create inspirational works of city-scale public art, often featuring natural elements, such as water, ice, and fire.

My work as a public artist is also an act of service. It is inspiring to gather together to make a positive statement about an entire community’s intention to make the world a better place. What better time for such a statement than at the moment of graduation, when students, informed by their studies and nurtured by the faculty, set forth into the world of opportunities before them?

President Casey has asked the entire Colgate community to examine how campus rituals such as graduation have been celebrated, and to imagine how one might renew and expand them to mark accomplishments, triumphs, service, transitions, and joy.

We face these issues in a time when newly emboldened voices of hatred have emerged in our nation. They are voices of anger and hate that some thought were silenced long ago. The purpose of those groups promoting such hatred and violence is to divide the nation. They hope to undermine the progress we are making towards realizing the vision of a “nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all … are created equal.”

Across the country there is legitimate alarm and anger over the rise of such hatred — and agreement that we must condemn such activities. Many citizens are seeking to redress these grievances and hope “with charity for all,” to be able to help “bind up the nation’s wounds.”

Colgate, as a community and as an institution, is deeply committed to opposing such racism and to fighting for justice and social equity. Even so, some people have feared that the Torchlight Ceremony might have connections to the Ku Klux Klan or the Nazis, or even if unconnected may be seen as an extension of recent hate-filled protests. These questions have, in turn, troubled some who have long cherished the traditional Torchlight Ceremony. In the light of these concerns and knowing that a university is a place of learning, President Casey asked for a deeper examination of the history, meanings, and the expression of the Torchlight Ceremony.

It has been fascinating to explore the many meanings of Torchlight and its source, the lit torch on the Colgate seal. People often do not write down directly what things mean, but they do leave many valuable clues. I am not a historian, so think of the following as less of a history lesson and more of an interesting mystery story, one with many pictures.

For several years, some members of the Colgate community have expressed concern over the nature of one of Colgate’s most long-standing rituals — the Torchlight Ceremony. They express concern that it might have connections to the Ku Klux Klan or the Nazis and thus racist intentions, connotations, or echoes. It may remind people of recent white supremacist marches in Charlottesville, Va. Others feel it is a beloved ritual is a cherished 85-year tradition that ties current students to generations of Colgate graduates, that the history of Torchlight is not connected to these disturbing histories, and that those who have participated in the ceremony in the past, or who now wish to, are not condoning racism or violence.

Concerns about Torchlight should be partially allayed by the knowledge that there is no evidence of any direct historical connection to the Klan or the Nazis, that the record reveals that the ceremony’s intention was to add beauty and meaning to graduation while building class solidarity and alumni engagement, and that the idea of the torch as representing Colgate’s mission had already been in place for some time.

Torchlight is, at its heart, a live re-interpretation of the 1846 Colgate seal, established long before the Klan or the Nazis even existed. Torchlight was designed in 1929 to celebrate the founding principles of the university expressed by the seal’s torch — a symbol that has represented truth, divinity, liberty, freedom, justice, inspiration, enlightenment, leadership, and a dedication to education for thousands of years. Rituals such as Torchlight are intended to build community engagement by reinforcing deeply held principles. It is unfortunate and tragic that the meaning of Torchlight is no longer understood by its participants.

Exploring the rich and fascinating history behind the torch on the Colgate seal may help alleviate many of the concerns. At the same time, we must also be respectful and compassionate of those who are offended or alarmed by the sight of a torch procession. We must acknowledge that, while not connected at the founding, other historical events occurred well after the Colgate seal was created that require our further examination. To explore this, we have to also look at disturbing images and analyze why they create such strong reactions and what motivations and intentions were embedded in these events. We must also sincerely understand that possessing such knowledge may not prevent or alleviate the shock or consternation or emotional distress that some members of the community may legitimately feel over Torchlight.

In such times, we need to find a way to come together to fight hatred by building unity and solidarity so that we may all work together to move our nation and the university towards justice, equality, and light. Yielding our symbols to allow racist demagogues to pervert their meaning is to aid the racists in their primary aim, which is to sow division and undermine our solidarity and commitment to achieving justice in this world. But at the same time, it is paramount that the ceremony at commencement be clearly not related to the alt-rights’ demonstrations of hatred, racism, and intimidation.

I hope that a better understanding of the intended meaning of the Colgate seal, will help us redouble our efforts to work together to advance the important work of bringing more justice and equality into the world. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. preached:

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate,

adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars.

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that.”

I hope that this first presentation on the original context of the Colgate seal and Torchlight and our subsequent discussions will result in better understanding of the original intent of Torchlight, and also help as we work on the creation of an enriched set of commencement weekend rituals that will properly honor the great accomplishments of the graduating class as well as underscore the distinction of the Colgate commitment to excellence.

Introduction to the research

For thousands of years in nearly every culture on the globe, fire has been seen as a divine element and a miraculous instrument of awe, power, and wonder. Thus the mastery of fire, now wielded purposefully by humankind, has universally represented culture and civilization with the torch being a symbol of liberty, freedom, inspiration, knowledge, and teaching.

Sadly, we know that mankind is also capable of evil and the torch is a tool that has occasionally been used also by purveyors of hatred. This website explores the long roots of these traditions, positive and negative, and places the torch in the Colgate seal and in Torchlight in its broader context. The torch is much more often a symbol of positive inspiration and accomplishment than it is an instrument of hate. Indeed, when fire’s positive symbolism is stolen and redeployed in the service of hate, it is revealing to understand the motivations of those appropriating such a universally understood beacon of hope.

Note: This page continues to be updated as conversation on campus continues.

The Colgate seal

The central symbol of the popular 1846 Colgate seal is a lit torch actively held aloft in the right hand. There has been no discussion of any change to the Colgate seal as the university enters its third century.

The inclusion of the hand makes clear the reference is to more than just light or divine fire, standing alone. The torch is a tool, wielded with direction, purpose, and intelligence. This is a reference to Prometheus’s gift of fire to mankind to allow the imaginative and active use of inspiration to create civilization. That the torch is held in the right hand indicates in some traditions that the action is grounded in faith, sincerity, and justice.

The seal represents light as truth and divine inspiration, actively carried forth, bringing light and knowledge out into the dark world and passing that light from one person to another.

Light symbolism is found in most religions — shown in the halo, aura, nimbus, sun, fire, moon, and stars.

In university seals, light is often depicted as well, shown often in a form of fire directed or controlled by mankind, such as in torches, candles, lanterns, campfires and lamps; often including a hand to indicate the necessity of engaged attention; or with a number of torches passing the light on from one generation to another, or carrying light forth from the institution to bring light and learning into the world.

The earliest version of the Colgate seal shows a torch that has a pointed base, soon replaced with a small sphere. The symbolic intention here means to convey that the torch can only remain upright, and hence stay alight, through the active engagement of human intervention holding the torch aloft. In the Catholic mass, the liturgical torches are specified to be “non–freestanding” for the same reason, and are also to be held in the right hand.

Lawrence Hall was completed in 1926, just three years before Torchlight was proposed. Its unusually detailed pediment features two lit torches and the seal’s motto. Perhaps the finishing of this bold neo-classical entrance revived interest in Colgate’s torches.

Light in the Baptist tradition

Colgate’s origin as a Baptist seminary informed the seal’s design, because the Baptists see light as a manifestation of Christ. The Anabaptists, known also as German Baptists, were active in Pennsylvania and New York and often used the symbolism of Christ carrying a torch. The largest printing project in America before the American Revolution was the printing of Jan Luyken’s religious works. Illustrations in Luyken’s influential work “Jezus en de Ziel” included engravings titled “Christ illuminates the darkness with a torch for the personified soul” in both the original 1685 edition and, with a new plate, in the revised 1714 edition.

Colgate started as the Baptist Education Society of New York (1819), which became the Baptist Literary and Theological Seminary, which then became Madison University. At that time three professors who taught the core of theology studies, created the familiar Colgate seal of a hand holding aloft the lit Torch of Truth and Divine Redemption. Just to make sure we understood its meaning and didn’t forget, the good professors actually spelled it out for us in Latin (then a required language to graduate), Deo ac Veritati.

The seal’s Latin motto “For God and Truth” establishes the religious intent of the seal’s torch symbolism. The hand-held torch represented the 13 founders’ intention for the original Baptist Seminary to educate young men to go forth and do missionary and evangelical work in both the West and in the far east. The delightful mural in Merrill House depicts the scene in 1824 when “the first missionary leaves for the foreign field.” The Baptist tradition favored inspired preachers, often unschooled. Rev. T. Harwood Pattison, a Colgate graduate, in his influential book The Making of the Sermon (1898) advised: “Preach as did Francis of Assisi, ‘compelled by the imperious need of kindling others with the flame that burned within himself’.”

The neatly cuffed sleeve shown so deliberately on the first versions of the seal is important. In heraldry the cuffed arm in this style (formally referred to as “vested” or “habited”) would indicate clergy; as opposed to the bare (“proper”), maunched, or armoured arm. The exceedingly plain, buttoned cuff on the Madison Seal reflects the sartorial restraint of the Protestant and Baptist traditions.

Note how the rhetoric of the cuff is used to differentiate between the Native American chief and military officer in the 1817 Indian Peace Medal. Many of these Peace Medals were given to chiefs in the central New York area. This medal was designed by John Reich, of Philadelphia in 1817.

The religious intention of the designers of Colgate’s seal is further confirmed by a curious detail related to the Great Removal Controversy, when half of the Colgate divinity faculty “removed” from Hamilton to establish the Rochester Divinity School in 1850. The remaining divinity faculty also left Colgate to join their brethren in Rochester in 1928 to create the Colgate Rochester Divinity School. The new 1928 seal of the reunited faculty featured the two torches brought back together again, inscribed with the two founding dates of 1819 and 1850.

The religious intention of the designers of Colgate’s seal is further confirmed by a curious detail related to the Great Removal Controversy, when half of the Colgate divinity faculty “removed” from Hamilton to establish the Rochester Divinity School in 1850. The remaining divinity faculty also left Colgate to join their brethren in Rochester in 1928 to create the Colgate Rochester Divinity School. The new 1928 seal of the reunited faculty featured the two torches brought back together again, inscribed with the two founding dates of 1819 and 1850.

Teaching is the passing of knowledge on to the next generation, and “passing the torch” is an often used metaphor. The importance of sharing and passing knowledge and inspiration from person to person is often expressed:

“Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire in the mind.”

– Plutarch 100 CE

“As one lamp lights another, nor grows less, so nobleness enkindleth nobleness.” (Inscribed in the reading room at the Library of Congress)

– James Russell Lowell 1868

The original Baptist seminary in Hamilton, N.Y., was to train clergymen for missionary work. The Gospel of John praises the work of John the Baptist, depicts Christ as “the light of all mankind,” and promotes the missionary work of bringing light to everyone so they may become “children of light.”

“In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind.

The light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness has not overcome it. . . .

The true light that gives light to everyone

was coming into the world.”

— John 1:4-8 [NIV]

“Jesus told them … ‘Whoever walks in the dark does not

know where they are going. Believe in the light while you

have the light, so that you may become children of light.’”

— John 12:36-37 [NIV]

“Christ illuminates the darkness with a torch for the personified soul”

Jan Luyken (Anabaptist) from “Jezus en de Ziel” (1685 & 1714 editions)

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was another Baptist who often used light symbolism in his sermons. Dr. King’s seminary joined with the Colgate Rochester Divinity School after his graduation.

The torch and the hand in the heraldic tradition

The theology professors who designed the Colgate seal would have been familiar with the importance of both fire and the hand in heraldry as well as the message of righteousness contained in using the right hand. In Aaron Ward’s 1747 New Dictionary of Heraldry he states that “Fire is the source of the arts, without which scarce any could be brought to perfection. … Alchemists … discover such secrets as are wonderful in nature. In [heraldry] fire may denote those who being ambitious of honor, perform brave actions, with an ardent courage in the service of their prince or country; their thoughts are aspiring.”

The hand is “the most absolutely necessary of the parts of man, as serving for all sorts of actions, and even to denote our very thoughts and designs. Among the Egyptian hieroglyphics the hand denotes power, equity, fidelity, and justice.” The Colgate torch is held in the right (or “dexter”) hand which indicates that the action is grounded in faith, sincerity, and justice.

The Torch of Leadership

The Promethean gift of fire to mankind is often shown as a torch and is used to express leadership, creativity, invention, civilization, and inspiration. The torch processions and torch races in ancient Greece were held five times a year, honoring Prometheus and four additional gods. They were so important that the torch was included on coinage, shown here with Apollo on the obverse. (357 BCE)

Shortly after Torchlight was established at Colgate, the Promethean torch was used as the central metaphor for the Rockefeller Center, with the 1934 unveiling of the sculpture “Prometheus” commissioned for the center from American artist Paul Manship. The gilded Prometheus presides over the Rink at Rockefeller Center with a quote from Aeschylus carved in the red marble behind him.

The Torch of Knowledge

Light represents knowledge and wisdom and is seen to illuminate the dark world through learning, scholarship, teaching, invention, observation, and study. The Torch of Knowledge was used as a symbol during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment in most western cultural traditions. In the United States, the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress is crowned with the Torch of Knowledge.

You are greeted in the library foyer with a figure holding aloft the Torch of Knowledge, and you encounter hundreds of representations of the torch throughout the building in murals, architectural ornaments, doors, plaques, stained glass, wall sconces, uniforms, etc. The Torch of Knowledge is thus often used on many college, university, and library seals, logos, diplomas, awards, and emblems throughout the world.

The Torch of Knowledge is invoked in the tradition of Persephone’s torch-lit descents to the underworld of death and her return each spring. Her torches represented her power and knowledge of paths to the forbidden world of the dead, and thus illuminated the mysteries of the unknown. The Torch of Knowledge was the frontispiece to Jean Desmartes’ “La Vérité des Fables …” [“The Truth of Fables … ”] in 1648.

The Torch of Freedom and the Torch of Liberty

The hand-held torch has long been the symbol of freedom and liberty. In particular, it has been used to represent civil rights and human rights by the Nobel Peace Prize, the NAACP, and the UN’s Declaration of Universal Human Rights. The Statue of Liberty (1886), a gift from the people of France to the United States, was formally titled “Liberty Enlightens the World” by the artist, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi.

The metaphorical female figure of Liberty, champion of freedom, is based on the Roman goddess Libertas, who was the patron of freed slaves. Her image is first used politically in the United States by Paul Revere in 1766 and then included by Thomas Paine in “The Liberty Tree.” She is called Columbia for the first time in a 1776 poem by the black slave poet Phillis Wheatley.

The Torch of Freedom, so central to Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty, was based on the “Torch of Freedom” traditionally said to be held aloft by the statue The Colossus of Rhodes in the South Aegean off the coast of Turkey. The Colossus, erected in 280 B.C., was the same scale as Bartholdi’s statue in New York City and depicted Helios, the God of the Sun, another symbol of freedom. The dedication to the Colossus spoke of its “lovely torch of freedom and independence.” There are different interpretations of the statue’s pose and whether “the torch of freedom” was held aloft, or was adjacent to the figure. Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Colossus” makes this reference explicit.

The Torch of Truth was used in a political cartoon in 1798 in London. The Torch of Liberty was used in Germany in 1813 to celebrate the liberation of Hanover in an ink drawing by Johann Heinrich Ramberg. Honoré Daumier’s political cartoon “Libre Pensée” [Free Thought] in Paris in 1869 showing clerics, Jesuits, and other conservative leaders trying in vain to blow out the flames of the “Torch of Free Thought.”

The Promethean linkage to freedom is lyrically proclaimed in Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound (becoming celebrated just as the university seal was designed). Prometheus, long punished for giving fire to mankind, is freed from bondage and celebrated in its closing paean.

To suffer woes which Hope thinks infinite;

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night;

To defy Power, which seems omnipotent;

To love, and bear; to hope till Hope creates

From its own wreck the thing it contemplates;

Neither to change, nor falter, nor repent;

This, like thy glory, Titan, is to be

Good, great and joyous, beautiful and free;

This is alone Life, Joy, Empire, and Victory.

The Torch of Liberty has been used in many of the United States national symbols and seals and was included among the original suggestions for the national seal. One of the ways to establish the national accepted understanding of our symbols is to examine the extensive use of the Torch of Liberty on US coins, currency, medals, and stamps.

The Torch of Freedom is also used extensively on US stamps, including the 1940 stamp “The Torch of the Enlightenment” issued as part of the “National Defense Issue”; the 1943 “Four Freedoms Issue” based on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Speech, in which he identified the Four Freedoms. The design for the 1 cent postage stamp “The Torch of Freedom” was personally selected by President Roosevelt based upon Paul Manship’s painting “Liberty Holding the Lighted Torch of Freedom and Enlightenment.”

The 1948 stamp on the 85th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address features a torch to commemorate President Abraham Lincoln’s speech declaring our nation as “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” as does the 1960 stamp from the American Credo Issue “Liberty – Patrick Henry.” Later stamps used the Torch of Liberty to honor NATO, Rotary International, “Liberty For All,” and the Alliance for Progress.

The Torch of Liberty and the Torch of Freedom are frequently invoked, starting with the Augustus Saint-Gaudens 1905 design of the 1907 Double Eagle $20 gold piece. Saint-Gaudens had already used torches on the medals for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago where they represented accomplishment, honor, invention, creativity, and leadership and on his 1895 Smithsonian’s Hodgkins Medal for discovery and science. The Torch of Knowledge was on the medal designed by Champlain for the 1900 Paris International Exposition.

The Torch of Leadership was featured on medals such as the US Medal for Lifesaving on Railroads (1906) and the Harriman Medal for Leadership in Safety (1913). The Torch of Liberty was featured on Liberty bonds ads for both World Wars and in WPA posters for the War effort. The Torch of Freedom was used in Presidential Citizens Medals by both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy and the National Bicentennial Medal in 1976. The Torch of Knowledge is used on the NASA medal for Outstanding Leadership Award and the US Library of Congress Living Legend Medal.

The Torch of Freedom was often invoked in official and popular iconography as part of the American effort to fight both world wars as a representation of our defending democracy and freedom. The torch was used explicitly as a symbol of American’s fight for freedom against the Nazis in federal posters and in political cartoons.

This is echoed to this day in torch processions that commemorate the liberation of European cities from the Nazis by American soldiers, such as the annual torch Procession for Tolerance that commemorates the liberation of the Dutch city of Eindhoven from the Nazis. The Roosevelt “Liberty” dime was struck specifically to commemorate the forces of democracy defeating the Nazis and fascism in WWII — with “Liberty” on the obverse and the Torch of Liberty on the reverse. The equivalent motivation lead to the issuance of the 1945 Churchill Victory Medal featuring the Torch of Liberty commemorating victory over fascism.

The Torch of Freedom, always held aloft and in the right hand, is quite often used for civil rights and human rights issues. The U.S. Commemorative Silver Dollar coin was struck in 1964, to celebrate the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and it depicted a stylized torch with three entwined flames. The 1993 US Commemorative Half Dollar coin to honor the “Bill of Rights and our basic freedoms” featured a hand held flaming torch.

Other US Commemorative coins featuring torches include the coins struck for the centennial of the Statue of Liberty in 1986, including the “Nation of Immigrants” Silver Half Dollar, the “Ellis Island” Silver Dollar, and a series of other coins including the various commemorative coins for the various Olympic games.

Internationally, the Torch of Freedom is depicted in many places specifically for human rights, such as on the 1978 San Marino stamp commemorating the 30th anniversary of the 1958 Universal Declaration of Human Rights with a painting by Renato Guttuso.

The 1949 national poster for the NAACP 40th anniversary Nationwide Membership Drive featuring a painting by African-American artist Charles Henry Alston (1907–1977) showing a black man holding a torch aloft in his right hand.

President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania in 1961 established the ‘Mwenge wa Uhuru’, which means “Torch of Freedom” in Swahili. The Torch became known as the Uhuru Torch and is the national symbol of Tanzania’s independence and represents “freedom and light.” It was first lit on top of Mount Kilimanjaro and is carried all across the country every year. The Uhuru Torch of Freedom is featured on stamps, currency, and coinage and was lit in 2016 by Tanzanian Vice President Samia Hassan for its annual race to honor freedom.

The First Torchlight Ceremony

In 1929, the Alumni Corporation, under the leadership of Frank Williams, Class of 1895, decided it was important to build more alumni engagement with the university and to honor and celebrate the senior class in a deeper way. They conducted a comprehensive survey of Colgate’s commencement program. A subcommittee researched other universities’ commencement programs and sent representatives to attend those ceremonies. They are likely to have seen the introduction of the Olympic torch ceremony for the first time in Amsterdam in 1928. Their work informed the creation of a new Colgate commencement program that was announced to the alumni in the fall of 1929.

The 1930 commencement was just six months after the panic associated with the 1929 stock market crash, so this was a senior class that was graduating into an entirely unknown future. Many families of those graduating, and returning alumni, were certainly facing a profoundly different world for the first time.

Thus, the original aims of the Alumni Council of creating a powerful new ceremony of inclusion, support and engagement had only become even more important. Further, Williams died suddenly in February of 1930, so he never saw the ceremony he helped to design. Because of his passing — and the recent untimely deaths of three members of the Class of 1930 — Torchlight was, in part, also a memorial service with four memorial orations. One can easily imagine why the Torchlight Ceremony had such a deep impact. It gathered the entire Colgate community together, now including alumni for the first time, back to the campus for commencement where they created a circle of torchlight to illuminate and surround beloved Taylor Lake with an unbroken circle of support. Facing an uncertain world, the entire community gathered together in an expression of unity that had spirit, gravitas, solemnity, reflection, and beauty at its core. The local paper of the day reported that it was visually stunning and beautiful and that, through a program of group singing, music, and oratory, it fully realized Williams’ hopes.

The Torch Tradition in the military

Popular culture has focused on the Nazis and the use of torches for the Nuremburg Rallies featured in the 1935 film Triumph of the Will. This has obscured the fact that all military forces made extensive use of torchlight displays and marches dating back to the Romans. Thus the use of torches by the Nazis was more a reference to a long-standing tradition than an innovation.

Starting from the return to camp from civilian leave (with torches to light the way), military forces around the world have developed many torch traditions. Military processions and marching with torches was recognized in 1596 and expanded widely in the Netherlands in the early 1800’s. The German ‘Großer Zapfenstreich’ and the English ‘Torchlight Tattoo’ became a popular part of many military presentations in Scandinavia, the US, England, Scotland, Germany, Switzerland and India.

English forces presented the Torchlight Tattoo for both grand royal occasions and matter of state ceremony, as well as for popular gatherings. The photos show torch processions in Aldershot in 1894, for the King’s birthday, in Bordon, England, in 1905, and in Wembley Stadium in 1924. The Mysore Police present an annual military parade procession as part of the Dasara Festival in Mysore, India. German forces participated in torch parades and reviews long before the Nazis and still do to this day, such as at the Großer Zapfenstreich, presented in Bonn, Germany in 2002 (now presented to the music of Shostakovich’s “For the Peace of the World”). The U.S. Army still presents torchlight reviews and tattoos in Washington, D.C., at the annual US Army Torchlight Tattoo Procession at Fort Jackson, and elsewhere.

Torch use by the Ku Klux Klan

The torch is a universal symbol, and like any symbol or object, it can be used negatively or positively. Both the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis used torches in their rallies. Torches were not unusual for the period prior to 1930, and thus torch processions were not original with them. The Colgate seal was designed in 1846 long before the Klan or the Nazis existed. The Torchlight Ceremony was established in 1930 before the Nazis came to power in 1933, and there is no documentation of any connection between the Klan and Torchlight at its founding.

The Ku Klux Klan’s symbol of hate was a large stationary flaming cross, not torches, and the Nazis used existing torch traditions and incorporated them into their popular rallies and the propaganda created by the German film director Leni Riefenstahl. She expanded the longstanding ceremonial troop assemblies to create large German processions, with massive architectural sets, searchlights, full orchestras and choruses, plane flyovers, massive choreographed teams of soldiers, music, banners, grand opera, and props to make propaganda films for the Nazis from 1934 on. To explore any possible connections between Torchlight and the Klan or the Nazis we must go into more detail into the ideology, symbolism, and sources of these two despicable and hateful movements. For completeness, we are including images from the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis, which are disturbing to view.

Before looking into the intentions and context of Torchlight as established in 1930, it is important to note that in 2018, the issue of torch processions is much more contested ground. While there is no evidence that Torchlight was ever intended in 1930 to refer to the Klan or the Nazis, the expanded use of torches by contemporary neo-Nazi hate groups and right wing demonstrators creates a complex field of competing identifications and meanings that the Colgate community continues to debate and discuss. This complex current context is difficult to interpret as each viewer comes to it with many different perspectives. This ambiguity over the meanings of torches in 2018, must be a part of the larger decision on what current practice should be.

The Ku Klux Klan had at least three different manifestations with changes in their intentions, membership, leaders and activities; with wide regional variations. Thus blanket statements beyond declaring them a terrorist, racist, pernicious, and violent organization are difficult to make. In general, torches were not much used by the Klan through 1930 (though there were exceptions). As noted, more recently, several racist organizations with neo-Nazi and racist ideologies have been using torches.

The early Klan emerged in 1865 during the post-Civil War Reconstruction period as a covert, loosely-organized, terrorist operation engaged in intimidation, murder, and assassination of both black and white activists and leaders of reconstruction. The Klan was heavily suppressed by the post-Civil War governments and effectively eliminated by federal authorities under federal laws passed in 1871 and 1872. They concealed their identities behind dark cloaks and masks and operated usually at a distance in an odd mixture of disguises that seem to be derived from many sources and varied widely from group to group. As they were outlawed by both local and federal law, they operated deep undercover in darkness and were careful to use disguises and not draw attention to themselves with something as visible as torches or a procession.

The second incarnation of the Klan was founded in 1915 in response to the 1905 novel The Clansman by the Rev. Thomas Dixon Jr., after it was popularized by the 1915 film by D. W. Griffith The Birth of a Nation. The novel and the film were deeply bigoted, hateful, and biased works of political agitation that gained a wide audience. The film was noted for its advanced technical accomplishments, but its message was deeply racist and inflammatory. This second reemergence of the Klan was established by William J. Simmons in Georgia and it involved a professional organizational approach with a sales and PR staff all funded by membership dues and sales of regalia. Simmons greatly expanded the range and membership of the Klan and used the film The Birth of a Nation for promotion.

Rev. Dixon’s novel The Clansman introduced the “Fiery Cross of old Scotland” as its symbol. The illustrations by Arthur Keller showed a burning cross, with costumes based on popular romantic images of the Crusades, all heavily featuring the cross as icon, emblem, and symbol. This second version of the Klan accordingly adopted the burning cross as their symbol based on The Clansman and the film. It is important to realize that the Klan’s symbol at this time was now a large, stationary, explicitly Protestant Christian, burning cross. They rarely used torches, as the cross was meant to be the main central source of light, thus referencing both religious gatherings and divine authority. Photos also show the Klan illuminated within a circle of car headlights creating an illuminated field of light. The Klan can be found occasionally using torches in this period, particularly to light the cross, but torches would be a departure from their proscribed ceremony. The U.S. Library of Congress has a photo of a Klan rally in 1936 carrying torches in Florida. Another indication that the cross itself was of the most significance is the existence of photos of Klan rallies occurring grouped around crosses that are illuminated not by flames, but crosses with rows of electric lightbulbs projecting from the staff and crossbar of the cross

The film The Birth of a Nation led to a terrifying resurgence of the Klan that started in 1915 in Georgia with a cross burning at Stone Mountain. The newly constituted Klan was still violent and racist and anti-black, but they had now expanded the targets of their hatred to include Catholics, Jews, and immigrants. The efforts of Simmons were directed to creating a much larger and specifically a more lucrative organization. Using new organizing techniques, Simmons grew the Klan in membership to frightening levels and they were estimated to have 5 to 6 million members at their peak in 1925, including representation in upstate New York, particularly in and around Buffalo. The Klan’s membership reflected a frequently observed split, with its members largely coming from rural areas. The Klan famously marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.D. on August 8th, 1925 with 25,000 to 40,000 participants.

Three months later in 1925 the Klan’s growth ended precipitously with the sensationalist conviction of the Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon for a brutal murder, rape, and kidnapping, along with other trials around the country for Klan violence, as well as internal dissension and power struggles. These court convictions for violence, testimony from witnesses, and internal power disputes exposed the Klan for the terrorist and murderous group it always was and permanently ended its move toward wider acceptability and expansion. Many members left in 1926 and 1927, though there was a smaller march on Pennsylvania Avenue of 12,000 to 15,000 people in 1926. Nationally 99.5 percent of all prior members had left by 1929. This version of the Klan was reviled from 1926 on and, in the north few would choose to associate with the Klan by 1927. The second version of the Klan remained active on a smaller scale on the south, particularly in Florida through the 1930’s.

The third era of the Ku Klux Klan regrouped after World War II as a more violent organization, no longer organized nationally. It emerged in many areas of the south, often only locally organized. This third version of the Klan was actively engaged in terrorism and in active opposition to the expansion of civil rights and voter registration. This Klan was associated with many heinous acts and notorious murders from the late 40’s through the early ‘70’s. Their violent legacy is still connected to current neo-Nazi ideology and violence. This Klan was involved in many murders that included the 1963 assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, the 1963 bombing of the 16th St. Baptist Church in Birmingham that killed four young girls, the murder of the three Freedom Summer marchers, and many others. The NAACP, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, the House Un-American Activities Committee, and others were active in fighting back and eventually restricting the activities of the Klan in this period.

Since then, the neo-Nazi, the new right, Storm Front, Unite the Right, and other right wing hate groups have returned to the streets to preach hatred and division as they did in Charlottesville in August 2017 and elsewhere. The shooter who killed Pastor Clementa Pinckney and eight other people at a bible study class in 2015 at the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Church in Charleston, S.C. was motivated by a mixture of Klan, Nazi, and Confederacy related racist material he found on the internet. Some of these groups, such as the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August 2017 have used torches as part of their imaging and their symbolism.

Colgate’s Torchlight Ceremony first occurred in 1930, when the Klan, after the trial, was in decline in the north and subject to vehement public, political, and press attack. There is no documentary evidence suggesting any connection. The collapse, opprobrium, and the public repudiation of the Klan from 1925 on, particularly in the north, means that it is very unlikely there is any connection between Torchlight and the Ku Klux Klan. Further, the Klan’s symbol was a flaming, stationary cross, not torches, so there is little room for a connection for the inspiration or meaning of the Torchlight Ceremony when it was founded.

However, the more recent use of torches by neo-Nazis creates a complex set of conflicting symbolic meanings that has led to the current impasse on campus, where the founding symbolism, the intention of the current torch bearer, and the interpretation of each viewer in light of Charlottesville can be genuinely, and understandably, entirely and profoundly different.

Torch Use by the Nazis

German student groups and other traditional processions had used torches since the early 1800’s. Among them, the Burschenschaften was a series of student social associations first established in 1815 and inspired by liberal and patriotic ideas with the motto “Honor, freedom, fatherland.” When they achieved one of their aims with German unification in 1871, many left the movement, leaving the remaining students to drift to the right. They were supportive of Hitler as he rose to power and was eventually appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933. That night Joseph Goebbels, who had been in charge of propaganda since 1929 for the Nazi party, organized a torch procession through the Brandenburg Gates by the Chancellery building as a show of power using, party members, party militia, youth groups, and members of the right-wing Burschenschaften. Though a pivotal event, much praised in Nazi propaganda, its size was likely greatly exaggerated, in part due to the short notice. Photographs purported to show the event are thought to have been staged later for the cameras. In 1936, the torch procession was repeated in a far larger procession that was much photographed and filmed. This torchlight procession on the night of Hitler attaining power with his appointment as Chancellor became a defining moment for the movement and for the Nazis.

As seen on January 30, when the Nazis came to power in 1933, they under the leadership of now Propaganda Minster Goebbels immediately embarked on a major calculated effort to use intimidation and propaganda to consolidate and project political power. This effort was a coordinated and deliberate strategy of mass persuasion, across many media, often strong visual elements, deploying appropriated and stolen symbols and coordinated across many media, including film, music, radio, press, and printed materials. Film director Leni Riefenstahl filmed the 1934 Nuremberg Rally to create Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens) released in 1935. Riefenstahl, Goebbels and architect Albert Speer used massive modernized neo-classical architectural structures, searchlights, specialized lighting, massed troops, orchestras, full opera performances, flags, airplanes, battalions of armament, banners, music, vast scale, and innovative techniques to create the events and films. The program, expense and scale of the propaganda effort was massive, with the Nuremberg Rallies for the Nazi party becoming a larger annual showcase from 1934 to 1938, driven as much by the production needs of the intended propaganda films than anything else. The Nuremberg Rallies and Triumph of the Will has served ever since as a template for many films seeking to depict dystopian imperial power.

The Nazis and Riefenstahl used torch processions as part of the annual Nazi party Nuremberg Rallies and the resulting propaganda films, echoing the January 30th march. These were huge expensive productions and torches were used among many other elements and props. The torches solved many of the challenges of filming troop movements at night, so torches were also a technical innovation to build cinematic drama. Riefenstahl worked closely with organizers and Speer to plan the many different elements of the Rallies for their cinematic, visual and propaganda effects, including the use of theatrically focused electrical spotlights (which were so bright they would have made any torches absurd and invisible). The annual torch procession through historic Nuremberg’s main street was a more theatricalized extension of various long-established 19th century German ‘Zapfenstreich’ military torch procession traditions and other folk traditions. The Nazis chose Nuremberg specifically for its quaint, nostalgic buildings and streetscapes. Riefenstahl deliberately created and filmed many other real and invented nostalgic processions to illustrate supposed Germanic Volk traditions from peasant and farmer processions in historic garb, to extravagant “Arts Parades,” processions of Protestant clergy, youth and athletic brigades, and many marching bands, all perhaps best understood as part of a rhetorical attempt to create a mythical German Volk past. For similar reasons they created processions with the flags and uniforms of the old Imperial German Army to falsely imply legitimacy for the Nazi government.

New military and industrial technology and stark neo-classical architecture was featured, and a well-known symbol of power was Speer’s Cathedral of Light which became famous through Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda films and still photographs. Less well known is the fact that the Cathedral of Light was not an original German or Nazi project, but based on largely American advances in exterior lighting technology that had been debuted in displays in New York City in 1899, with particularly striking examples in San Francisco for the Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915 and the Ford Pavilion for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1934. Nazi propaganda was so effective that their thefts of other inventions and symbolic traditions became better known than the original sources.

The hosting and planning of the 1936 Olympics in Berlin was another large national propaganda effort by the Nazis, one with a racist premise that was elegantly shattered by Jesse Owens’ many successes on the field. Berlin had been selected as the host city in 1931, before Hitler came to power, and there was considerable controversy about continuing the games with the Nazis now in power. The Nazis appropriated and politicized the modern Olympic Games and tried to ban Jewish athletes, but relented in the face of promised boycotts. Again the Nazis commissioned and funded Leni Riefenstahl to film the Olympics and also be a design partner with the Olympic Games to help the event be the more effective subject for her propaganda film, Olympia, released in 1938. The Nazis had military parades march through the stadium and the opening ceremony featured a flyover of the enormous airship Hindenburg as a massive symbol of Nazi military might, painted with four swastikas and dangling the Olympic flag.

The ancient Olympic tradition of a torch and a fire cauldron during the games had been added to the Olympics in 1928 in Amsterdam and continued in 1932 in Los Angeles. The Nazis appropriated this tradition and expanded it to three cauldrons, now with added military and political displays. The Nazis introduced the idea of the Olympic Torch Relay with runners running from Mt. Olympus to the Berlin games as part of a larger internationalist intervention, all filmed by Riefenstahl.

While the German torch processions with the rightwing Burschenschaften had preceded the Nazi rise to power in 1933, there is little to suggest there was any connection or awareness of this symbolism in Hamilton. The first Torchlight Ceremony at Colgate was proposed in 1929 and first performed in 1930, so it was prior to the Nazis coming to power in 1933, Riefenstahl’s 1935 film, or the Nazi theft of the ancient Greek Olympic torch tradition in 1936. It was more likely influenced by the 1928 introduction of the Olympic torch first introduced at the Amsterdam games.

In Charlottesville, VA, outsider white nationalists carried tiki torches for a “Unite the Right” rally on the campus of the University of Virginia (UVA) on August 11, 2017. This was a clear connection back to the torch procession that greeted Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. The UVA students greatly resented their presence and held a counter vigil and procession with 5,000 participants on August 16 with candles, hymns, music, poetry and prayers to successively take back their campus from the invasion and challenge of the white nationalists.

A Note on the Klan’s and the Nazis’ Strategy of Appropriation of Cultural Symbolism

Both the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis are conspicuous for their violence, hatred, racism, bigotry, intimidation, rejection of democratic values, fear of outsiders, immigrants and diversity, suppression of free speech, homophobia, intolerance and their murdering of many people. Simultaneously they are both guilty of wholesale theft and appropriation of elements and symbols from many outside cultures and for then twisting the meanings of these symbols to add legitimacy to their organizations and thus support their immoral ends.

As mentioned before, from 1915 on the Klan’s symbol was not flaming torches, but specifically a large stationary flaming Christian cross. Their meetings and ceremonies featured the singing of hymns, prayers, and specifically Protestant messaging. Their overall animus was expanded beyond African Americans and now was also directed against immigrants in general, and Catholic and Jewish immigrants in particular. The Klan seems to realize the immoral, illegitimate and indefensible nature of their founding and purpose and then seeks to free to establish a false sense of acceptance by appropriating the symbols stolen from others, including the very people they malign, attack and kill. The cross is stolen to fill a spiritual void at the heart of the organization.

It should also be noted that the Klan grew from 1915 to 1925 because of some surprising and disturbing partnerships. The Klan’s active partners were the local Protestant clergy, the Woman’s Temperance Movement, and the other anti-vice social movements. The local police were often laxly enforcing Prohibition, which allowed the Klan to then illegally join the clergy and Temperance movements as an invited vigilante extrajudicial enforcer closing bars and liquor establishments in the name of “Law and Order.”

There misperception about torches and the Klan is revealing. The Klan was explicit that their symbol was a flaming Christian cross, but this is so jarring a realization to viewers that cognitive dissonance and an understandable refusal to cede the symbol of Christianity to a terrorist organization, seems to erase the memory of the cross, leaving only the memory of flames. Flames then seem to morph into a false memory of torches, mistakenly leaving the impression that the Klan primarily used torches, rather than a flaming Christian cross.

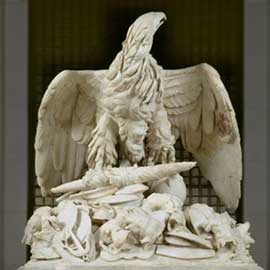

The ancient Roman funerary eagle that is behind many of our national eagle symbols

The Nazis have a similar heinous history of cultural theft, appropriation and ethnic vandalism. To conceal the violence and immoral methods they used to attain power they stole the symbols of the ancient Greek democracies and the Rome Empire to claim a false history. Their clipped, blocky interpretations of neo-classical architecture was a deliberate part of their propaganda, as was their use of the Roman eagle, the Promethean torch procession, the Roman Imperial standards, broad swords, fasces, laurel wreaths, olive branches, oak clusters, and the Roman stiff-armed salute. Their most famous theft was the swastika, a sacred and blessed symbol in the Sanskrit tradition and found in many other cultures as well.

The Nazi theft of these symbols was unjust and has left many of them now so stigmatized that they are no longer be used. There are examples where we have not allowed these symbolic thefts to stand, such as the American use of the Eagle, or the refusal to allow the cross to become contaminated by the Ku Klux Klan. Another example is the Olympic Torch Relay from Mt. Olympus to the Games that was first created by the Nazi propaganda offices and filmed by Leni Riefenstahl for the 1936 games in Berlin. The next Olympic Games were held after the War in London in 1948 and the Olympic Committee and the British refused to cede the Relay to the Nazis as a symbol and made this an Olympic tradition, now specifically reframed as a “Relay of Peace.” The Olympic Committee’s message for the meaning of the torch was “May the Olympic flame bring us the triumph of love over hate, of peace over war. Let this flame be a flame of love and confidence.” The first runner from Olympia was Greek army corporal Konstantinos Dimitrelis, who underscored the Olympic Committee’s intention to reclaim the torch from the Nazis and their message of peace by, during the ceremony, removing his army uniform and laying down his weapon before accepting the torch.

We must be equally vigilant about the symbols that America has also borrowed from these same ancient sources. It is sobering to realize that both the original American salute to the flag and the Olympic salute were abandoned because they were confusingly similar to the German “Sieg Heil” salute, based on the imagined original Roman Imperial salute.

American children performing the original correct American flag salute in 1915

The author of the 1892 Pledge of Allegiance, Francis J. Bellamy, also established the correct salute to flag during the Pledge — facing the flag, the right arm to be extended straight ahead, but raised, with the fingers together, but palm up. (Despite this instruction, many photos of this period show the salute being made with the palm down.) For 50 years Americans saluted the American flag with a stiff-armed salute until The U.S. Flag Code replaced (“the Bellamy Salute”) with our current form (with our hands over our hearts) in 1942, a year after we entered the war against the Nazis.

The Torch of Celebration

Throughout the world torchlight processions have often been a positive part of celebrating, honoring, and dignifying people and events across a very wide range of cultures and traditions. Here is a showcase of photographs showing the many positive celebrations that are related to the spirit of Colgate’s Torchlight Ceremony.

The torch has been a source of joy and celebration for more than 2,000 years as well as a symbol of freedom, liberty, and knowledge. The professors who chose a lit torch for the Colgate seal in 1846 did so with a firm grounding in history and symbolism, and this legacy deserves to shine forth brightly as Colgate enters its third century.

Photographs used here are from many sources, largely found among images posted by others on the Internet, and are used strictly for academic purposes. If you are the copyright holder, however, and wish to have your image removed, please contact communications@colgate.edu.