Exploring sacred forests

In Ethiopia, Christian Orthodox churches emerged some 800 years ago. Today, thousands of these sites protect some of the region’s last remaining native forests. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has awarded $500,000 in funding to a Colgate interdisciplinary faculty team, led by biology professor Catherine Cardelús, to continue investigating the status and conservation of sacred forests in Ethiopia’s northern highlands.

Sacred forests have survived in spite of changes in societies and the ways in which humans use their land. “Priests, monks, schoolchildren, and others are constantly walking and working in these forests, using them for everything from worshiping to schooling,” Cardelús said. “I hope to learn from those who already use ecosystems sustainably and leverage their methods to help others.”

To that end, Cardelús has tapped colleagues at Colgate and beyond to conduct an interdisciplinary study that will determine the current ecological health of the forests as well as changes in their structure and the perceptions of nearby populations over time.

She is joined on the project by Peter Scull (geography), Peter Klepeis (geography), and Carrie Woods, former visiting biology professor at Colgate, now at the University of Puget Sound. The team has also hired two scholars — Izabela Orlowska, an Ethiopia historian, and Alemayehu Wassie, a forester and Christian Orthodox Tewahido priest — to operate full time in the country.

Scull will use geographic information system technology, declassified reconnaissance photos, and satellite images to track changes in the quantity and extent of Ethiopian church forests from as far back as the early 1930s. Klepeis will survey community members’ perceptions of the forests, while Cardelús and Woods will measure the ecological health of the forests by studying the vegetation and analyzing the chemistry of the leaves and soils.

This type of NSF grant specifically spurs such cross-divisional investigation in order to encourage the education of the next generation of scientists. A dozen Colgate students will have the chance to travel to Ethiopia with the team during the next three years. Plans are already underway for a trip to Africa in March.

Cardelús first climbed into Ethiopian forest canopies back in 2009, thanks to a grant from Colgate’s own Picker Interdisciplinary Science Institute. Additional Picker funding backed research that laid the foundation for the team’s NSF application. Preliminary data have led to a series of intriguing questions that Cardelús’s team — and the NSF — would like to answer.

“A lot of people say that church forests are disappearing, but our research is showing that they are not,” Klepeis said. In fact, according to the group’s early findings, only four forests out of a collection of more than 1,000 have been lost since the 1960s. In some cases, the forests are actually expanding. But Klepeis also notes that while most forests persist, there are indicators of degradation, such as an increase in canopy openness and an increase in exotic species.

How can forests be holding fast or even growing since the 1960s in spite of villagers’ urgent needs for fuel and other products that woodlands provide? Do younger, more secular Ethiopians look upon forests in the same way as their more religious elders? “I am keen to understand why and how these forests persist and the mechanisms for the differences in ecological status among them,” Cardelús said. “Why are some more resilient than others?”

These questions, transiting the social and physical sciences, are more than academic. “Scientists, social scientists, and humanists usually work independently and in isolation, which has often led to poor decision making for conservation,” Cardelús said. “Success would be the development of a conservation model for Ethiopian church forests, and applying this in other regions. After three years, we hope to have the model.”

— photo above by Peter Klepeis

Syllabus

HIST 312A: History of Colgate

Jason Petrulis

Bicentennial Research Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor in History

T/TR 9:55-11:10 a.m., 535 Case-Geyer

Course description: This course invites students to revisit Colgate’s history in preparation for the university’s 2019 bicentennial celebration. This semester, it will focus on “Race and Colgate,” analyzing recent discoveries about Colgate’s rich and complicated history of diversity, inclusion/exclusion, and race-making (the construction of race). Through weekly work in archives and primary sources, and through analysis of secondary readings, we will expand Colgate’s history — telling new stories about the people, things, and events that built our university.

Class format: This course is a laboratory for practicing history, with biweekly sessions split between hands-on research in Colgate’s University Archives and a classroom session focused on discussion and collaboration.

Key assignments/activities: Students produce “public history” — a museum exhibition, a digital history website, and a history research paper.

The professor says: “Our student-historians will be helping to bring new stories to light. We have known so little about Colgate’s history of diversity — about our Native American students in the 1820s, Asian students in the 1840s, African-American and Latino students in the 1850s — that every class session brings a surprise. What’s more, it’s a chance to broaden the number of voices who tell our stories so that the bicentennial belongs to all of us.

“History of Colgate is the first course in a program supported by the president and provost, in which professors teach classes inspired by the bicentennial. These creative classes will also help us look forward to a third century of innovative teaching and research.”

Students roll out online course for kids

A lot of science, engineering, artistry, and culture have gone into that piece of crusty, buttered bread devoured at the dinner table. Those elements are the basis for a new open online course, BreadX, that was launched by Colgate first-year undergraduates for use by students, grades 6 and up, worldwide.

BreadX: From Ground to Global, on the EdX Edge platform, guided participants in scholarly exploration of one of the world’s most ubiquitous foods and its global connections. It started November 15 and lasted 10 days (but is still available online).

Fourteen Benton Scholars in Professor Karen Harpp’s first-semester seminar developed the course, from concept to production and implementation. Content included the origin of bread ingredients, food distribution, cultural perspectives, and the global picture.

“Bread can teach us about culture, science, society, and how we can conquer the challenges that face the world today,” said Jennifer Lundt ’19, of Santa Barbara, Calif.

“This online course is perhaps the first ever designed by students, for students (or at least one of the first),” Harpp said. “This is really a new approach to online education, in that it is a community experiment in global online course design.”

In designing the course, the Colgate students included materials to engage young audiences, with short supplemental readings, fun videos, and discussion points, explained Oneida Shushe ’19, of Albany, N.Y. “One of our goals is to create this caring online community, and one of the ways to do that is to foster a discussion,” she said. “No matter where you [take the course], bread is probably a big part of your life.”

At press time, 297 students had participated in the course; the median student age was 17. “Seeing people from all around the world come together to participate in something we created from the depths of our brains was absolutely amazing,” Lundt said.

Student research pumps resources into Madison County

Thanks in part to research conducted by a Colgate geography and environmental studies student, Madison County will receive more than a half-million dollars in federal funding for well-water testing and remediation to take place during the next five years.

Kayleigh Bhangdia ’16, of Poughquag, N.Y., worked with the Madison County Department of Health last summer via Colgate’s Upstate Institute to examine where private drinking wells may be threatened by known contaminated sites, spills, agricultural runoff, and bulk storage locations.

Bhangdia used geographic information systems (GIS), which she learned about in a Colgate course, to examine U.S. Department of Environmental Conservation statistics about spill sites and dangerous ground-water issues. She then overlaid that information onto a map of Madison County private wells, upon which nearly half of the local population relies for drinking water.

“There could be huge distributions of contaminants and no one would know, given the lack of regulation,” Bhangdia said.

Geoffrey Snyder, Madison County environmental health director, said Bhangdia’s analysis also helped to point out locations of potential well and aquifer contamination related to geological conditions.

Madison County was one of just 20 recipients of grant funding nationwide from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. The grant will pay for a full-time water resource position, water-quality tests of residential wells, and the creation of a project committee to improve the county’s capacity to respond to water contamination incidents, according to Snyder.

“The professional qualities exhibited by [Bhangdia] and the high level of GIS skills [she brought] to our health department, will continue to make these collaborative opportunities of great value to this office,” Snyder said.

“Kayleigh developed strong skills at Colgate that will serve her well as she pursues a career in public health after she graduates,” said Julie Dudrick, Upstate Institute project director. “She benefits from having the opportunity to further develop those skills in a community-based setting, and her work benefits our community at the same time.”

Bhangdia said that “working at the health department was an extremely rewarding experience. I really felt like part of this community.”

Mapping the web

Until just recently, no one had ever successfully mapped Internet data flow in the United States. Working with a team of researchers, Joel Sommers, associate professor of computer science, created a map of the cables that help the data flow. His work was featured in Technology Review magazine.

“Other researchers have tried to map the Internet,” said Sommers. “However, all of those attempts have [been through] taking traffic measurements or using other measurement tools to try to build a picture of the Internet from the top down.” The problem with previous attempts is that they see a virtualized topology — not the real physical infrastructure.

Because the cables that power the Internet are owned by many different companies, including AT&T and Level 3, the information was in a number of places. By painstakingly putting together ISP (Internet service provider) maps and then cross-referencing against a massive set of public records, the team was able to create one of the first maps of the Internet’s long-haul fiber-optic infrastructure in the United States.

Understanding the topology of the Internet can help protect it, Sommers explained. For example, in 2001, a tunnel fire in Baltimore melted fiber-optic cables, causing Internet outages. Having a picture of the Internet’s true topology can help engineers understand the potential impact of such events on other portions of the network.

Colgate takes next step on international journey

On Oct. 15, 2015, Colgate ushered in a new era for internationalism on campus when it officially celebrated the opening of the Center for International Programs (CIP). The center now serves as a hub for the university’s numerous global initiatives conducted by professors and students.

In its new home on the first floor of McGregory Hall, the CIP brings together the Office of Off-Campus Study, the Lampert Institute for Civic and Global Affairs, and also the New York Six Consortium. Additionally, it will be home base for international students studying on the hill.

The space features a wired conference room suitable for international video conferencing, a lounge where students and professors can prepare for — and debrief from — study- abroad adventures, and a kitchen.

Gifts from Ed ’62 and Robin Lampert brought the center to life, and the Lampert Institute is proving to be a pivotal member of the university’s international programs ecosystem. The institute, led this year by philosophy and environmental studies professor Jason Kawall, is funding student and faculty research at home and abroad. The institute is also coordinating campus events around the theme of food, with related lectures on global food scarcity, nutrition, food resilience in the face of climate change, and more.

The university is building international partnerships that are already resulting in new faculty and student exchange programs. Most recently, Colgate expanded its three-year relationship with Xiamen University in China.

The CIP is a natural step on an international journey that is as old as the university itself, from its early incarnation as a Baptist seminary, training students for missionary work abroad. More recently, in the early half of the 20th century, the university began to establish study groups led by its professors. Today, Colgate offers nearly 20 off-campus study groups and allows students to use financial aid resources to cover more than 100 other approved programs in 50 countries.

Knowing that two-thirds of Colgate’s student body studies abroad for at least a semester, a Working Group on International and Global Initiatives called for the creation of the CIP in 2013.

Barking up the right trees

By examining young trees in Brazil, Adam Pellegrini ’10 found that previous predictions of carbon emissions in forest regions might have been underestimated by as much as 50 percent — an indication that there could be a bigger environmental threat than scientists previously thought.

Trees burned by fire release varying amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. The amount depends on factors like the fire’s intensity, the local climate, and the tree’s physical makeup. One critical variable is bark thickness, which determines how quickly fire will overheat the inside of the tree trunk and cause the tree to die.

Pellegrini spent weeks climbing trees and scraping bark from 155 species that dominate Brazil’s Cerrado region. His aim was to determine bark thickness among new-growth trees in savanna areas previously hit by fire. Because those trees root in carbon-loaded soil, their destruction might be especially dangerous to the environment.

“Fire is being introduced into areas that didn’t used to experience it,” said Pellegrini, whose work was published in Global Change Biology. “Trees in savannas are predicted to grow more because of increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but a lot of the species increasing in savannas are sensitive to fire.”

By identifying which species thrive after fire — and how well their bark protects them from future events — scientists can make more accurate climate-change predictions. Those predictions, in turn, could help land planners and government officials make smarter choices about controlled burns and prevention strategies.

Pellegrini’s research in Brazil likely has implications for other ecosystems, too. As a National Science Foundation graduate research fellow pursuing a PhD at Prince-ton, Pellegrini is collecting plant trait data for species from around the globe to develop new vegetation models. His data could one day be used to quantify total carbon emissions from fires in Africa, South America, or the Pacific Northwest.

While he was an undergraduate at Colgate, Pellegrini worked with Catherine Cardelús, associate professor of biology and environmental studies, to research pollution in Costa Rica’s rainforest canopy. Cardelús noted that Pellegrini’s multidisciplinary approach to studying ecosystems — he has also published on animal behavior and geology — puts him in a good position to dig deeper as a climate researcher.

Although he’s moved onto different ecosystems, Pellegrini said working with Cardelús pushed him to ask “big questions.” In pursuit of answers, he is determined to not overlook critical traits that others might have discounted. “When people are modeling the carbon cycle of the globe, they try to simplify these fundamental plant communities,” Pellegrini said. “But whether or not you get those key characteristics right makes a big difference.”

— Kimberly Marselas

Shining light on atmospheric chemistry

Deep in the forest, the same chemicals that give pine trees their smell might have a powerful effect on climate change.

Sunlight can convert those naturally occurring molecules into secondary organic aerosol (SOA) particles with the potential to change local cloud cover and rainfall patterns. SOAs also help to determine how much sunlight reaches Earth and how much long-wave radiation escapes.

Professor Ephraim Woods, chemistry department chair, is training high-powered lasers on aerosols to see if molecules like pinene, limonene, and isoprene can form SOA with the sun’s help. Backed by a $285,500 grant from the National Science Foundation, Woods and his student research team measure the lifetime of the short-lived chemical species that spark these reactions, as well as how much particulate organic matter they create. The goal is to determine which conditions promote the formation of SOA particles.

A single ultraviolet pulse allows the team to spur a photochemical reaction that might lead to particle growth. If so, they’ve got just a few nanoseconds to monitor the minuscule, highly unstable species using the light of a second laser pulse.

“Our experiment provides a new way to monitor these reactions,” said Woods. “The potential effect of these reactions on the environment is greater the longer these reactive species exist, but how long they last depends on what else is in the neighborhood.”

Woods tasks his students with setting up technically challenging experiments that vary the particles’ organic composition or the pressure at which the chemicals are studied.

“Our students are partners in the work,” he said. “They have become quite sophisticated in their approach to it.”

For Woods, giving undergraduates a chance to collect and help interpret the data is equally as important as his research findings. “Working with student researchers is my favorite part of my job,” he said. “It engages students in problem solving and connects them with a broader scientific community.”

— Kimberly Marselas

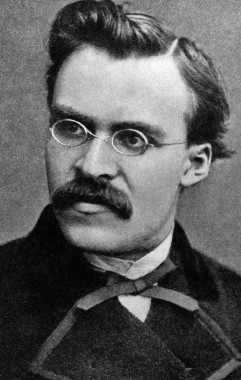

The Nietzsche you never knew

Morality, spirituality, and the condition of the soul: these were a few of the topics addressed when Colgate philosophy professors and other distinguished scholars devoted a weekend to the study of Friedrich Nietzsche at the end of September. The conference included lectures by experts from around the world as well as a panel discussion on Nietzsche scholarship.

The event was held in honor of Maudemarie Clark, George Carleton Jr. Professor of philosophy emerita, who retired from teaching at Colgate after 28 years.

Clark knows just about everything there is to know about the German philosopher (and there is certainly a lot to know). For those who aren’t as schooled as Clark, we found nine Nietzsche factoids:

- His father was a Lutheran pastor, but Nietzsche was a harsh critic of Christianity.

- Spent part of his life stateless after annulling his Prussian citizenship

- Was offered a professorship at the University of Basel in Switzerland at age 24 before he completed his doctorate or became teaching-certified

- Taught classical philology (the interpretation of Greek and Latin texts)

- Served as a medical assistant during the Franco-Prussian War

- Wrote poetry

- Loved music and was friends with Richard Wagner, the famous opera composer, until they parted ways

- Believed that a day without dancing was a day wasted

- Had a mental breakdown — reportedly after witnessing the beating of a horse — and spent the last 11 years of his life incapacitated