Linking living with learning

This fall, 200 sophomores and 200 first-year students will move into the first of four residential learning communities (RLCs). The much-studied model of living and learning in one place shows students making a smoother transition to college both academically and socially, said Dean of the College Suzy Nelson.

The new RLC system, intended to become the centerpiece of a Colgate education, is built on personalized mentoring relationships, with professors partnering with staff members and students to provide direction and purposefulness. A number of first-year seminars will be taught in the residences, where professors will also hold office hours and meet with advisees.

“We hope residential learning communities will fundamentally shape students’ lives,” Nelson said, “by fostering health and wellness, and teaching them that embracing diversity where they live is a way of furthering human understanding.” The idea for this Dean of the College/Dean of the Faculty collaboration came out of Colgate’s 2014–2019 strategic plan, Living the Liberal Arts in our Third Century.

The pilot RLC, in Curtis and Drake halls, will be co-led by Rebecca Shiner, professor of psychology, and Mark Shiner, university chaplain. The Shiners bring expertise in human development and well-being, a history of creating co-curricular programs, and, said Rebecca, “idealism about the power of living together well.” Mark said he hopes to “help new students feel welcome and returning students feel part of something meaningful.”

Colgate will build on this model each year; by 2018, all first- and second-year students — as well as some upper-level students — will live in faculty-led residence halls on campus. Each learning community will be affiliated with an annex on Broad Street, where older students will live. Annexes will give each RLC space for sponsoring social and cultural events, and keep members connected throughout their four years at Colgate.

The second RLC, to open in fall 2016, will be located in Bryan Complex. In April, the Board of Trustees approved funding for the schematic design of a new residence hall that is expected to be home to the third and fourth learning communities.

Working to bring the future communities to life are co-directors Antonio Barrera (history, Africana and Latin American studies) and Pilar Meija Barrera (Romance languages); Jeff Bary (physics and astronomy) and Mary Simonson (film and media studies, women’s studies); and Frank Frey (biology, environmental studies) and Brenda Frey (advancement).

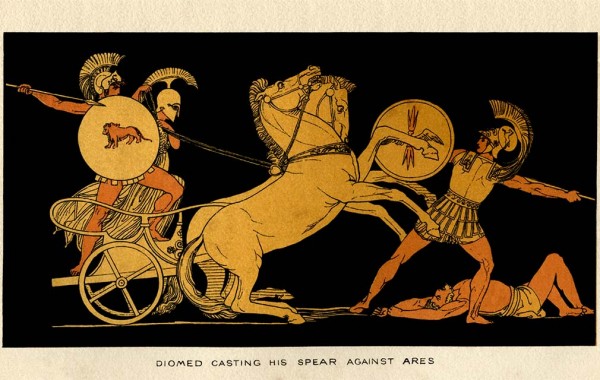

Greeks at War

When a course’s subject matter dates back to antiquity, it can be challenging for students to find meaning. Robert Garland combatted this in Colgate’s first massive open online course (MOOC), Greeks at War: Homer at Troy. Integrating voices of modern-day veterans, Garland drove the discussion to pertinent topics such as the possibility that Achilles suffered from PTSD, and the benefits or detriments of daily contact with family members for soldiers at war.

Recollections from veterans, many of them connected with Colgate, highlighted parallels between modern wars such as Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Cold War and the ancient Trojan War. Garland, the Roy D. and Margaret B. Wooster Professor of classics, even shared the experiences of his own father. “He had been a prisoner of war,” he said. “I found myself reflecting on him and drawing him into the discussion at various points.”

The six-week course attracted an enrollment of 3,735 individuals from 106 different countries. Students responded to prompts posted by Garland, interacting online with him and others registered for the course.

Having previously offered courses through Udemy.com and the Teaching Company, Garland used his developed online education skills to broaden Colgate’s reach, while serving a sizable Colgate audience, including parents and alumni.

For Garland, offering MOOCs to a wide audience “gives the humanities, particularly the classics, visibility and meaning.” Other liberal arts institutions seem to agree; in May, Davidson College, Hamilton College, and Wellesley College joined Colgate in a new consortium focused on online teaching and learning, including on the edX platform.

“The Internet has offered [Colgate] the possibility of reaching out far beyond its boundaries to people of all ages and backgrounds,” wrote Garland in a closing letter to his online students. These individuals had the opportunity to connect academically with people they would never have interacted with otherwise.

— Story by Emma Loftus ’16; iStock photo

Honoring Harpp

Whether the topic is volcanology or the advent of the atomic bomb, Professor Karen Harpp’s innovative, engaging approach has made her a campus legend. For that, her list of teaching accolades now includes the 2015 Jerome Balmuth Award for Teaching and Student Engagement. She is the sixth faculty member to win the award, which was created through a gift from Mark Siegel ’73.

Described by students as “clear, helpful, approachable, and motivating,” Harpp (geology and peace and conflict studies) exemplifies the kind of teaching that Siegel wished to acknowledge with the award named after another legendary teacher, Jerry Balmuth, Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of philosophy and religion emeritus.

Harpp arrived at Colgate in 1999 from Lawrence University, where she began her career as assistant professor of chemistry. Currently head of the Benton Scholars Program, she was the first Colgate professor to offer an online course via the university’s edX platform.

“You constantly need to find new and better ways to have students collide with material,” she said. “That means not being afraid to experiment with new technologies.” It’s a lesson she learned from her father, an organic chemist who teaches at McGill University. From her mother, a high school teacher, she learned that, “the entire world can be your classroom, which opens up endless possibilities for new ideas.”

In keeping with those lessons, Harpp has taken students around the globe, teaching them about World War II on the beaches of Okinawa and about geology on the shores of the Galapagos Islands.

(Photo by Lorenzo Ciniglio)

Body language

The way a woman carries herself is integral to how she is perceived — in the workplace, in academia, and in the world. These are the findings of a new study published by April Bailey ’14 and psychology and neuroscience professor Spencer Kelly. While it’s not always the case for men, Bailey and Kelly found that body language and other nonverbal cues are incredibly meaningful in the perception of power in women.

Participants were shown images of men and women in both dominant and submissive positions, rapidly followed by power-related vocabulary words such as “coercive,”“powerful,” “passive,” and “compliant.” They were then asked to classify the images as either dominant or submissive. Bailey and Kelly measured how many errors participants made, along with their reaction times, in an effort to determine if the words and images implicitly shared the same theme.

“For women, nonverbal displays appear meaningful,” said Bailey, who double majored in women’s studies and psychology at Colgate. “How they hold their bodies seems to impact the ways that they’re perceived, at least during rapid impressions, whereas for men, gender might be more important. Even men in submissive poses were not rapidly associated with submissiveness.”

“Picture power: Gender versus body language in perceived dominance” was the culmination of Bailey’s senior honors thesis, completed under Kelly’s guidance. She had been a research assistant in Kelly’s lab and enjoyed working with him, so she developed a thesis topic that would combine their interests. “Spencer let me run with the idea,” Bailey said.

After the Journal of Nonverbal Behavior published their co-authored article online, Susan Krauss Whitbourne, a psychology and brain science professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, took their findings one step further in Psychology Today. “For women, if you want to appear powerful, you have not only to walk, but [also] to stand and sit [powerfully],” she wrote. “It doesn’t take designer clothes, expensive suits, killer heels, or even short hair, to show that you’re in charge. Your body’s pose will tell it all.”

Bailey continues to explore the subject in the social psychology PhD program at Yale University.

— Emma Loftus ’16

Real-world problem, real jury

When the students in Strategy and Security: Theory and Practice presented their proposals for security development in Somaliland, they were judged not only by their instructor, but also an official from the self-declared independent state.

The spring 2015 peace and conflict studies class explored the co-evolution of military practice and ideas of security. For their final project, course instructor Jacob Stoil gave students the challenge of proposing a development plan for Somaliland, with a budget of $15 billion plus $1 billion per year.

Stoil had invited Rashid Nur, Somaliland’s head of mission representative to the United States, to join him in hearing and evaluating the students’ proposals.

Drawing inspiration from key military strategists like Giulio Douhet, Julian Corbett, Alfred Thayer Mahan, and Mao Zedong, students applied the strategy principles they had learned to the context of Somaliland. To ensure the stability of the nation both in the short term and the long run, one group tackled the problem through military, economic, and international relations perspectives. For example, they suggested that Somaliland establish trade relations with China. This would not only allow Somaliland to better tap the potential of the fishing industry, but would also result in more secure waters and international flotillas. Most groups also talked about boosting border security with Puntland, a country that has a territorial dispute with Somaliland.

Nur said that he was impressed by the performance and knowledge of the five groups who presented. “What they suggest are the priorities of Somaliland. I will ask Professor Stoil for their proposals to read more thoroughly,” said Nur. “Although Somali-land is a functional democracy, it is still unrecognized internationally, and that affects the maintenance of security and the growth of the economy, which are the two big challenges Somaliland faces today.”

During his visit to Colgate, Nur also delivered a talk titled “Somali-land: Security and Development in an Unrecognized State,” and dined with a few students.

“Somaliland is a good case for students to synthesize what they have learned,” said Stoil. “This project is like a bridge between theoretical and reality, and is a practical level to learning.”

To the students, such a high-stakes presentation was an interesting challenge. “I think the biggest challenge for this project was to decide what was the most important, practical, and efficient strategy,” said P.J. Benasillo ’17, a member of the winning team, from Staten Island, N.Y. “That really gave us a perspective about strategy analysis in the real world.”

— Quanzhi Guo ’18

How to: Buddhist chanting

After a whole week’s work, how would you start your weekend? Every Friday this past spring, approximately 10 people from the Colgate community joined Professor Mahinda Deegalle for an hour of Buddhist chanting. Born and raised in Sri Lanka, Deegalle is a Buddhist and scholar who has authored many books, including Popularizing Buddhism: Preaching as Performance in Sri Lanka.

During the chanting sessions, Deegalle used a traditional collection of sayings of the Buddha written in Pali. An English translation helped students understand the meaning.

To try chanting yourself, here’s what Deegalle says you need to know — or not know!

— Iris Chen ’17

1. Relax. There is no fixed position. When you begin a session, pick your favorite spot in the room. Sit on a chair, a cushion, or just on the floor. Choose your most comfortable position, and start. Chanting is a kind of meditation. All you’ll need is to relax and let the sound carry you away. Many Americans feel uncomfortable meditating because of the silence, but during chanting, there is no awkward silence.

2. Break down the syllables to learn the pronunciation. Once you know how to separate syllables and how to read them together, the rhythm of the poetry becomes easy. My students only spent about 10 minutes learning each verse!

3. Just do it. When you first start to chant, you might be nervous about whether you are pronouncing the words correctly — but don’t worry. The repetition and musicality of the text will help you master it, and after that, you don’t need deliberate effort to continue. Once you learn everything and get going, it becomes like a song.

Speeches and sushi

The Japanese speech contest celebrated its 13th year this April with a lineup of 13 competing speakers, food, and performances. Organized by Professor Yukari Hirata, the event provides students with an opportunity to improve their language skills and gives members of the local community a chance to share their interest in Japan. The contest judges are Japanese people from the surrounding area; two of them have been a part of the event since the beginning.

“It’s amazing to see how students benefit from the continuity,” said Hirata. “Few have the guts to [compete] as a first-year student, but after watching the event, more will sign up in the following year. By their fourth year, people are ready to shoot for first prize.”

This was the case with classics major Elizabeth Johnson ’16, who watched last year and decided to give it a try this time. Her speech, about her internship at a tatami shop (making traditional Japanese floor mats), earned the Japanese Culture prize. Although she was initially nervous, she said, “When it was time for me to deliver my speech, I was really excited because I had worked really hard on it.”

Dang Minh Nguyen ’15 was one of the few brave enough to participate in the contest when he was just a first-year student, but his approach has changed since then. “I used to spend more time polishing my grammar and practicing, but this year I decided to write a little more loosely.” It clearly worked, because his speech about graduation won the prize for humor, and the audience hardly stopped laughing throughout his delivery.

Although he is not a Japanese major, Nguyen said that he feels like one, and many others who regularly participate in the contest feel similarly.

The cultural highlights included a choir, a taiko drum performance, and a traditional tea ceremony. During the reception afterward, attendees sampled a variety of Japanese food, such as yakisoba (fried noodles) and inarizushi (rice inside thinly sliced tofu).

“We want to be open to people who are vaguely interested in Japanese culture, even just in anime,” Hirata explained, “so they come in, eat food, and mingle.”

— Story by Meredith Dowling ’17; photo by Zoe Zhong ’17

No man is an island

Turquoise waters, white sand, and azure skies give the beach at Anse Cafard the guise of a tropical paradise. But “you feel like something really horrible happened there,” said Mahadevi Ramakrishnan, who leads Colgate’s alternative spring break trip to Martinique.

More than just a feeling, 20 8-foot-tall somber stone statues line the beach and symbolize a darker past. In 1830, a slave-carrying ship crashed and capsized; the shackled slaves aboard drowned. “Being there, everything is so light, the sun, the weather, it’s beautiful… And then you have the weight of these statues,” said Ali Kadhem ’17, who went on the trip this past March.

A Romance languages senior lecturer, Ramakrishnan has taken groups to the Caribbean island four times. This year, students studying French and those in her ALST/FRE 226: Interplay of Culture, Language, and Identity in Martinique class spent six days learning about a history steeped in colonialism and slavery. As Kadhem said, “The experience taught me how to become a traveler, and not a tourist.”

Jessica Pearce ’18 commented on visits to a sugar plantation and a distillery where the students learned about the manual labor required to produce rum. “I couldn’t have comprehended it fully without being there, seeing all of the manpower involved and thinking about how many people had to sacrifice their lives for the production of a good,” she said.

At a local high school, the group spent one morning helping Martinican students with their English in exchange for learning about the Creole language. They left having made friendships and shared contact information.

A walk through the rainforest included a tour of a greenhouse with plants used for medicinal purposes. Pearce was enthralled to scratch and sniff the bark of a cinnamon tree they passed.

Kayaking through mangroves to observe the island’s ecosystem and biodiversity, the group also noted the symbolism of the mangrove’s resiliency. “A pod can be dropped anywhere, and it will still flourish and grow,” Pearce said. Comparably, much of the Martinican population is rooted in slaves having been brought to the island, and despite the “three centuries of brutality, they rise above,” added Ramakrishnan.

Act 2

A week after returning to campus, students dug deeper into their exploration of slavery, race, and identity — on stage, with members of the theater department.

The collaboration began earlier in the semester when Christian DuComb, a University Theater professor, contacted Ramakrishnan about an intriguing discovery. His friend Andrew Daily, who is a University of Memphis history and French professor, stumbled upon a historically valuable play from the 1970s that was buried in Martinique’s archives. Titled Histoire de Negre (Black History), it compares the anticolonial struggle in Martinique with the civil rights movement in the United States.

Daily and Emily Sahakian, a French professor from the University of Georgia, translated the play from French and Creole into English. Through a Colgate Arts Council grant, Daily and Sahakian then spent a week working with students — providing historical context and helping them digest the content — for their on-campus performance on March 29. “This play is intense and quite raw,” Ramakrishnan explained. “We wanted to make sure that the students were emotionally and intellectually prepared.”

Pearce recalled reading the play in class before the trip, “and elements of it didn’t make sense to me. But after going to Martinique, it all started to connect.” The group also recognized commonalities between what they’d learned and current events. “I could understand the importance of performing this play, especially on campus after the sit-in last semester,” Pearce said. “People sometimes forget that what happened in history still makes an impact on our behavior now. Tying them together made me more aware of the fact that we don’t live in a post-racial society.”

Finale

On another stage, this time in New Orleans, La., the educational and personal journey concluded for this year’s group when four of Ramakrishnan’s students formed a panel at the Caribbean Studies Association Conference. The students were Laine Barrand ’17, Nicole Jackson ’18, Matthew Kavanagh ’17, and Linh Le ’18. Ramakrishnan supported them from the audience as they played the taped performance of Black History and reflected on the experience as a whole.

“I was impressed and touched by how much thought and work had gone into their presentations,” Ramakrishnan said, “particularly the connections that they drew between the play, the class, and their experiences during the trip.”

“The trip and the conference helped to actualize my studies; they showed the pertinence and realness of what we studied in class,” said Kavanagh. “In this context, the performance took on a new meaning for me, one of necessity and importance in the development and expression of a society that most of the world knows nothing about.”

As for Ramakrishnan, she’ll continue to educate others about Martinique’s complex identity — not only with future students, but also with her new book: Interplay of Cultural Narratives in Martinique (Caribbean Studies Press).

— Aleta Mayne