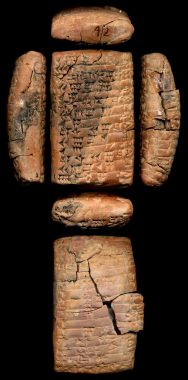

Above: A 3D-printed model of a cuneiform from Colgate’s collection

3D printing the past

Call it modern Mesopotamian claymation. With the help of the latest Artec3D equipment, archivists and instructional technologists at Colgate have teamed up to produce 3D scans and models of the university’s collection of 4,000-year-old Sumerian cuneiform tablets.

The ancient Sumerian people of Mesopotamia developed cuneiform — one of the earliest systems of writing. They created the tablets by using a blunt reed to press a design into wet clay and making recognizable wedge-shaped marks. Colgate’s collection comprises 48 cuneiform tablets documenting the trade of goods like silver, fish, flour, and sheep.

“Our cuneiform tablets and most of the tablets that you find are economic texts, like receipts and accounting records,” said Sarah Keen, university archivist and head of special collections.

The artifacts are often used in Colgate classrooms as teaching aids for courses in anthropology, sociology, and related subjects. “They allow students to study the primary goods that were traded and what fueled these economies,” Keen added. “[A tablet] gives you an entrée into some aspect of that society.”

Instructional technologist Doug Higgins partnered with Keen and Colgate’s conservation technologist, Allison Grim, on the project. They were joined by Ian Roy from Brandeis University and Jordan Tynes from Wellesley College.

“Three-dimensional scanning, modeling, and printing will allow us to bring the archives out of the boxes and to the Colgate community both locally and globally,” Higgins said. “We have the ability to share the artifacts digitally or to bring the models up the hill and have a closer study of the items within the classroom without fear of them being damaged.”

Handheld 3D scanners work by gathering a steady stream of photographs as the object is rotated. The scanner then uses software to stitch those photographs together in order to generate a model that measures to a 10th of a millimeter for accuracy.

The digital cuneiform models have already proved useful as educational tools. Professor Tony Aveni has used the models to supplement his anthropology course Comparative Cosmologies by projecting them onto the 32-foot wide screen of the Ho Tung Visualization Lab.

“My students had the opportunity first to handle the cuneiform, hold them in their hands, and see what they look like,” Aveni said. “Then we did a projection in the visualization lab of the 3D scans so that you could rotate them, spin them around, and look at the flip side. It gives students another perspective of the artifacts they’ve seen. These are marvelous teaching aids.”

The success of this cuneiform scanning project leaves Higgins hopeful for others like it in the future. One potential application of this technology is the 3D scanning of Colgate faculty research. Higgins envisions professors capturing 3D scans of archaeological sites abroad and bringing the images back to share with students.

He said, “I’m excited to see what we can do next.”

— Brianna Delaney ’19

Engineering Club reaches for the sky

Somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, a Styrofoam cooler filled with GPS equipment and GoPro cameras floats toward Nova Scotia. The cooler is actually the body of a weather balloon designed and built by the Colgate Engineering Club.

The club launched the balloon on October 5 and tracked its flight via satellite GPS. It passed within a quarter mile of the Ho Science Center and then drifted east until atmospheric pressure burst its balloon, thus triggering its parachute and dropping the cooler into the ocean 70 miles off Cape Cod.

“The balloon reached a height of about 120,000 feet, which is three to four times the height that a commercial airliner flies at,” said physics major Brendan Corrodi ’18, the club’s president and co-founder. “If we had the video, you could see the curvature of the Earth.”

The group continued to track the cooler as it floated in the ocean; physics majors Stephen Paolini ’18 and Austin Chawgo ’18 led the mission to recover it. They contacted the Cape Cod Coast Guard for help and used public-access GPS data to reach out to nearby fishing boats.

“A lot of the boats in the area were commercial, non-trap lobster boats,” said Paolini, the club’s project manager. “They could potentially sail past and scoop it right up in their nets, but none of them were near enough.”

The balloon’s GPS stopped transmitting on October 9 and the group abandoned the rescue mission, but they hope that the cooler will make it to the shores of Nova Scotia intact and be found. “My phone number is on the side, so if someone finds it, we might get a nice present,” Corrodi said.

If the weather balloon makes it back to Colgate, the club will be able to recover the GoPro video footage of its journey and reuse the equipment for another launch. In the meantime, they can use the GPS data to analyze wind patterns, air currents in the jet stream, and even ocean currents.

— Emily Daniel ’18

Professors talk Zika

On Zika: “The possibility of local transmission through mosquitos remains the biggest public health concern.” (Photo by iStock/Dr_Microbe)

When confronted with government warnings and media headlines about a new global health threat, it’s best to speak directly to those in the know. Before heading home for Thanksgiving break, students and faculty had the chance to discuss the Zika virus outbreak with biology professors Geoff Holm and Bineyam Taye.

During the November 14 conference, sponsored by the Shaw Wellness Center and Global Health Initiative, Holm drew on his experience as a virologist to describe Zika’s structure and behavior.

“Zika is a plus-strand RNA virus, which means it has one strand of RNA that functions as its genome,” Holm said.

In this way, the pathogen — which is often spread by animals and insects — resembles Yellow Fever virus, Dengue Fever, and West Nile. In behavior, Zika is similar to a Xerox machine, relying on its unwitting host to help it replicate and export itself to other cells.

“Understanding these replication mechanisms is the purview of basic virology,” said Holm. “We try to identify targets for therapeutic intervention so that we can potentially stop the virus from replicating within the host cell.”

Zika has garnered widespread attention in recent years due to a rare syndrome response called microcephaly, a birth defect that Holm defined as decreased head volume and brain size with consequent central nervous system disabilities.

Symptoms of the virus are typically mild and may include conjunctivitis, joint pain, fever, and rash. These usually clear up within a few days.

Because 90 percent of Zika cases are asymptomatic, men and women may transmit the virus sexually without knowing they’re infected, posing a risk to pregnant women and women who may become pregnant.

Epidemiologist Taye noted that there had been more than 4,000 cases of Zika recorded nationwide as of November 2016, and more than 600 cases in New York City alone.

“To date, the only cases in New York State are in people who acquired the virus while traveling to Zika-affected areas, or through sexual transmission from someone who had traveled to those areas,” Taye said. “However, the possibility of local transmission through mosquitos remains the biggest public health concern.”

— Emily Daniel ’18

New research on measuring greenhouse gases

It turns out that we may have been measuring carbon emissions incorrectly all along. And not in a good way.

New research led by environmental studies and physics professor Linda Tseng, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology and reported in Scientific American, identified an overlooked source of greenhouse gas emission — from wastewater treatment — that may increase current greenhouse gas emission estimates from that sector by 13 to 23 percent.

The international body that recommends guidelines for greenhouse gas emissions accounting does not currently include wastewater treatment plant carbon dioxide emissions because they are considered to be from natural biological sources that are carbon neutral. Tseng, along with colleagues from the University of California–Irvine and the University of Melbourne, found that a fraction of wastewater emissions actually has fossil origin (produced from petroleum) due to the household use of man-made synthetic detergents and soaps.

“We hope this study would promote efforts to quantify greenhouse gas emissions more accurately, matching the increasing global interests to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” Tseng said. “The results of this research should be seen as an opportunity to reduce and sequester emissions from wastewater treatment and could help wastewater treatment facilities meet their emission goals.”

Letting the good be the enemy

Suppose, for a moment, that the Good Samaritan didn’t rescue just one person merely by chance. Let’s say that he spent his entire life walking up and down mountain passes, finding wounded travelers by the hundreds, spending his children’s lunch money on the medical bills. Would we still respect him?

When New Yorker staff writer Larissa MacFarquhar looks at the world, she sees heroes and do-gooders who go to moral extremes. In her November 15 campus presentation — part of the Lampert Institute for Civic and Global Affairs speakers series on Crossing Borders: Peoples and Cultures, Goods and Information — she drew the distinction.

Heroes have greatness thrust upon them by circumstances. We like them because we could see ourselves behaving in the same way if the tables were turned. Do-gooders, on the other hand, often make us feel uncomfortable, because their altruism stretches beyond the pale. They sacrifice their own comfort and often the comfort of loved ones. They don’t confine their good deeds to their own social spheres.

In her book, Strangers Drowning: Altruism at Home and Far Away, MacFarquhar profiles several of these do-gooders, including an Indian lawyer-turned-doctor who launched a leper colony and a husband-and-wife team who adopted 20 children who were unlikely ever to have a family because of age, race, or ill health.

Freud might have called their behavior moral masochism. Freud’s daughter would have spoken of altruistic surrender, the affliction that requires someone to obtain gratification through a proxy. MacFarquhar doesn’t buy it. “These people have a sense of purpose,” she said.

In wartime, MacFarquhar asserts, individuals are often called upon to make ultimate sacrifices. But decades have passed since World War II — the last time that Americans were asked en masse to think beyond the bonds of blood when calculating the value of life and property. Perhaps that fact has altered our perceptions of normalcy when it comes to performing good deeds.

Decide for yourself. Join the Lampert Institute audience for MacFarquhar’s presentation, archived at colgate.edu/macfarquhar, and ask yourself the same questions that guided her research: “Is there a sense of too much morality? Can you push it too far? What would a life of moral extremity look like?”

Syllabus

Cyborgs of the World, Unite!

Science Fiction from Russia and Beyond

Mieka Erley, Assistant Professor of

Russian and Eurasian Studies

TR 1:20–2:35 p.m.

Lawrence 201

Course description: What does it mean to be human? Can our species survive climate change? Can we build a utopian society on Mars? These are questions that science fiction — a genre that bridges the “two worlds” of science and the humanities — has considered for more than a century. Focusing on philosophical, ethical, and environmental questions, this course introduces students to a wide range of science fiction literature and film, with a strong emphasis on works from Russia, the Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe from the 20th century to the present day. Among other topics, we will discuss human-machine interfaces and ethics, life-extension and transhumanism, space travel and colonization, and the prospects and perils of the rationally planned society.

This course places questions of biological and social diversity at its center, moving past the “local and transnational” to the transplanetary, transhuman, and beyond. The works read in class interrogate the very borders that structure the world and our experience of it — borders between ourselves and others; between the human, the animal, and the machine; and between the “natural” and the “artificial.” Students have the chance to reflect on new forms of social organization and new ways of “being human” in a diverse and changing world.

The professor says: “This is the only science fiction course currently offered at Colgate, and I’ve been overwhelmed by the interest from students. Science fiction is valuable because it liberates us to imagine other biological, social, and political formations than the ones that now structure and dominate our world. Given the enormous changes that are already upon us, we need this space of creativity, inspiration, and ‘thought experiment’ more than ever.”

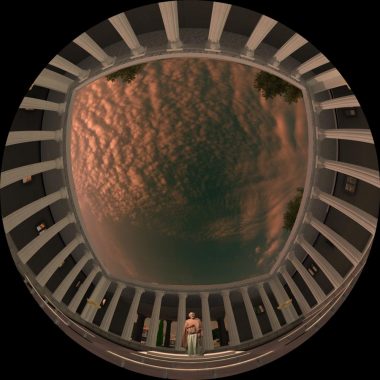

Socrates returns to life (momentarily)

Some say that the death of a great philosopher in Colgate’s Ho Tung Visualization Lab on October 27 was a miscarriage of justice and a stain on Athenian democracy. Socrates’ suicide, reenacted on the domed screen by actor H.C. Selkirk, didn’t require the response of law enforcement, but it did draw a crowd of spectators.

Students dressed in ancient Grecian garb ushered faculty, staff, and friends into the intimate theater on the Robert H.N. Ho Science Center’s fourth floor. The lights went down, and the audience was transported through time into the agora in Athens, digitally reconstructed during the past two years by Colgate University and Hamilton Central School students under the guidance of Vis Lab director Joseph Eakin.

The film, Socrates on Death Row, used live action and a voiceover by history professor Alan Cooper to tell the tale of one of Athens’s most famous citizens, who was a font of notable quotes and a deep thinker who never published. We know of Socrates’s philosophy and his eponymous method of Q&A through the writings of Plato and Xenophon. Relying on those texts, classics professor Robert Garland drafted the script for the show, which he considers a prequel of sorts to his previous show depicting the murder of Julius Caesar, Murder on the Ides.

Through Garland’s words, we hear of Socrates’s service in the Athenian army during the Peloponnesian War against the hated Spartans and their allies. We learn of his sympathy for nobles who would rather take government out of the hands of the hoi polloi. Socrates goes on trial for corrupting the youth and defends himself against his prosecutors, mostly by asking questions that make them look like fools. When the jury finds him guilty, he baits them into ordering his execution in an effort to prove the folly of their judicial system. We stand beside Socrates as he downs his dram of hemlock and sighs his last breath.

Thanks to Garland, Eakin, and their collaborators, the death of a classical hero demonstrates the life and vitality of Colgate’s interdisciplinary approach to liberal arts education.

“This is a new way of bringing the classics to a wider audience,” Garland said. “I want to show that classics is exciting, gripping, and that it can engage you.”

Eakin and his student staff have produced four full-length planetarium shows as well as flybys of the Grand Canyon, Rome, Mexico’s Teotihuacan, and other locales. “It brings these cultures to life when you can show what it was really like to be there,” he said.