Photography hits Close to Home

“Photography helps me figure out my place in the world,” said Linn Underhill, associate professor of art and art history, during the opening reception for her Close to Home exhibition at the Clifford Gallery.

Underhill candidly opened up about her personal struggles with the art of photography, her family history, and her search for her own identity when she introduced the show, which ran from February through April.

One of the most momentous points in Underhill’s journey with photography was visiting the childhood home of her father. He had died when Underhill was 12 years old, and she went to Sonoma County, Calif., 40 years later to search for traces of him. Underhill had been struggling with using a view camera, but realized that “suddenly, the camera was no longer my enemy.” Rather than forcing a perfect image, she said, “I [just] wanted to find some evidence of my father.” Two Polaroid pictures that she took of his ranch introduce the viewer to the exhibition.

The photographs in Close to Home are black and white as well as color. There are several series, including portraits of her neighbors that line one wall. Others emphasize nature and the changing of seasons. “One Year,” for example, delineates the passage of time by marking the seasons. Although distinct in their own way, each collection captures the beauty, and complexity, of everyday life — from scenic landscapes, to family gatherings, to a path mowed out of the grass in her 8-acre field.

“I have always been interested in photographs as a narrative,” Underhill said.

This exhibition deviated from her previous work — such as the Cosmic Dominatrix series, which relied heavily on the use of props, costuming, and a studio-controlled environment.

In Close to Home, Underhill explored the world outside the studio, and challenges the viewer to question how one experiences the passage of time and space.

(Photo above is Underhill’s Plenty:Davy)

— Marilyn Hernandez-Stopp ’14

Dancing with gender issues

In the last movement of her dance piece titled Wires, April Bailey ’14 (pictured in pink) breaks free from the group and moves independently — just as she’s demonstrated academically. Drawing from a famous essay by Marilyn Frye, Bailey choreographed and directed Wires as a complement to her women’s studies and psychology research on gendered ways of moving. Frye’s essay “uses the metaphor of a birdcage to explain how different iterations of oppression intersect to confine individuals,” Bailey explained.

The November performance, which drew more than 160 people to Brehmer Theater, concluded Bailey’s fall semester independent study class with Professor Mary Simonson.

“I was interested in using the communicatory medium of dance to discuss gender and sexuality, drawing from my academic training in feminist theory and gendered movements,” explained the women’s studies and psychology double major. (She has continued the research this semester for her psychology honors thesis.) Bailey, who began dancing at the age of 8, was mainly trained in classical Russian ballet, and is a member of Colgate’s contemporary/modern group FUSE Dance Co.

Featuring 17 dancers, Wires was composed of four movements. The first asked the audience to consider the ways that social mores and customs about gender constrict behavior; gender was marked by shirt color (blue, pink, or purple) following stereotypical associations. The second movement considered how sexual desire maps onto expectations about gender. The third presented one of the unfortunate consequences of strict gender norms: gender-based violence and manipulation. The fourth provided a space for rebellion and genuine expression of the self, regardless of gender stereotypes.

“A moving image is visceral, [so] people don’t get sidetracked by words that they don’t understand or that they have negative associations with,” Bailey said.

Indeed, some might be unfamiliar or uncomfortable with the topics she explores. The performance even took the dancers outside of their comfort zones, which was revealed during an engaging Q&A discussion afterward.

Sebastian Sangervasi ’14, who partnered with another male performer, remarked that “it was less the man-on-man contact that was weird for me, but more that I’m used to supporting [a woman], not being the one supported and releasing myself in someone’s arms.”

Danielle Iwata ’15, who performed a duet with Bailey during the fourth movement, also chimed in: “I was the masculine character, and it was definitely different for me,” she said, adding that another dancer commented that she wasn’t necessarily acting like a man but, rather, like a dominator.

“This discussion demonstrates the project’s effectiveness in inciting a conversation about gender and sexuality on campus,” Bailey said.

The project continues to influence Bailey’s work. “Wires made me examine the way my own choreography is affected by my gender identity,” she said. For example, in developing a piece for the spring Dancefest that is not about gender, she said, “I am conscious of cultivating a gender-neutral aesthetic and movement style to be mapped onto all bodies.”

The maze between Knecht’s ears

Professor John Knecht screened his animated short film Deluge and other works at Brooklyn’s UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art in February.

Professor John Knecht screened his animated short film Deluge and other works at Brooklyn’s UnionDocs Center for Documentary Art in February.

In Deluge, scenes of popping flowers, falling construction materials, and driving rain begged questions. But, “I am not providing the answers,” said the Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of art and art history and film and media studies.

He did, however, shed some light on his recent work during a discussion with Rebecca Cleman, the director of distribution at Electronic Arts Intermix. The conversation, Knecht said, was an opportunity “to be able to give the work a deeper context … to probe the maze between my ears.”

Examining the Holocaust through art

Striking images of Holocaust victims overlaid with paint and text stared back at viewers as they encountered the pieces in the exhibition One Day, One Woman, One Child. The exhibition was composed of 15 monoprints by Serbian-Canadian artist Gabriella Nikolic, who uses multiple screens and pigments for her printmaking process in which ink is transferred to paper from a plate that can create varying images. One Day, One Woman, One Child was on view in the Longyear Museum of Anthropology from November through February.

A collection of 20 Nikolic prints was a gift to the museum from Canadian benefactor Susan Robson in 2001, but they had not been publicly displayed prior to this exhibition. Thus, Sarah Loy ’15, under the guidance of Carol Ann Lorenz, senior curator, set out to research the images and texts incorporated into the art.

Loy did the research last summer with support from the J. Curtiss Taylor ’54 Student Research Grant in the Division of Humanities. She wrote the exhibition labels as well as an essay that analyzed the images and texts, placing them in the context of the Holocaust.

“I knew little about art, but I wanted to pursue this because I thought it would allow me to study the Holocaust from a new angle,” explained Loy, a double major in peace and conflict studies and religion.

The title, and the collection, are based on Nikolic’s Serbian family history, which was profoundly affected by the Holocaust. Fifty-two members of her family died in “one day,” but “one woman” (her grandmother) and “one child” (her father) survived. Nikolic’s work uses archival photographs and texts to place her ancestors’ personal story in the context of mass suffering. “In my work, I commemorate each and every one of them,” Nikolic wrote in her artist statement.

Several Colgate classes, including Jewish and German history courses, two first-year seminars, and a peace and conflict studies class, incorporated the exhibition. And the learning experience was not limited to Colgate students: thanks to Melissa Davies, the education coordinator at the Picker Art Gallery, a group of Hamilton high school students visited the exhibition as well.

As Loy reflected, “I have a new appreciation for the power that art has to look at tough issues and events like the Holocaust, and how it can expand on information given in books and other academic sources.”

— Hannah O’Malley ’17

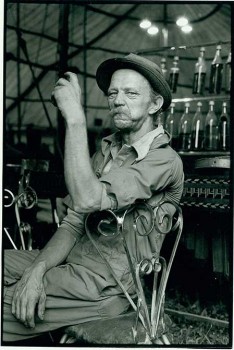

Photography by John Hubbard ’72

The work of the late John Hubbard ’72, longtime Colgate photographer and editor, was on exhibition at the Bennington (Vt.) Museum from February through March.

Faces of Bennington, 1972–1978: Photographs by John Hubbard featured more than 25 black-and-white portraits by the beloved photographer, who died in 2010.

While a sports reporter and photographer at the Bennington Banner in the ’70s, Hubbard took countless portraits of the people he encountered in the area.

Many of his images in the exhibition depict young progressive types including artists, craftspeople, and back-to-the-landers, as well as older people.