A scroll from India unfurls discussion among professors

Sri Lanka and Thailand and Andaman

The cursed tsunami snatched away lives.

A hundred-year-old sage said, “I’ve seen nothing like this before”

Why did you destroy, tell me (God), Thailand and Andaman?

The cursed tsunami snatched away lives.

Husbands lost their wives

What pain, merciful (God), what pain!

Why did you destroy, tell me (God), Sri Lanka and Andaman?

The cursed tsunami snatched away lives.

To protect people who are in tears

Why did you destroy, tell me (God), Thailand and Andaman?

The cursed tsunami snatched away lives.

They took pictures and said beautiful words to inspire people.

Why did you take so many lives (God)?

How did you know about the break in the ground?

Hearing the news, news reporters arrived

And here I end this poem of prayers.

My name is Momi Chitrakar and I am from West Bengal

The cursed tsunami snatched away lives.

Song and scroll by artist Momi Chitrakar

(Lyrics translated by Professor Navine Murshid)

On December 26, 2004, an earthquake in Sumatra, Indonesia, set in motion a series of tsunamis that bulldozed areas of southeast Asia and killed more than 220,000 people in 12 countries.

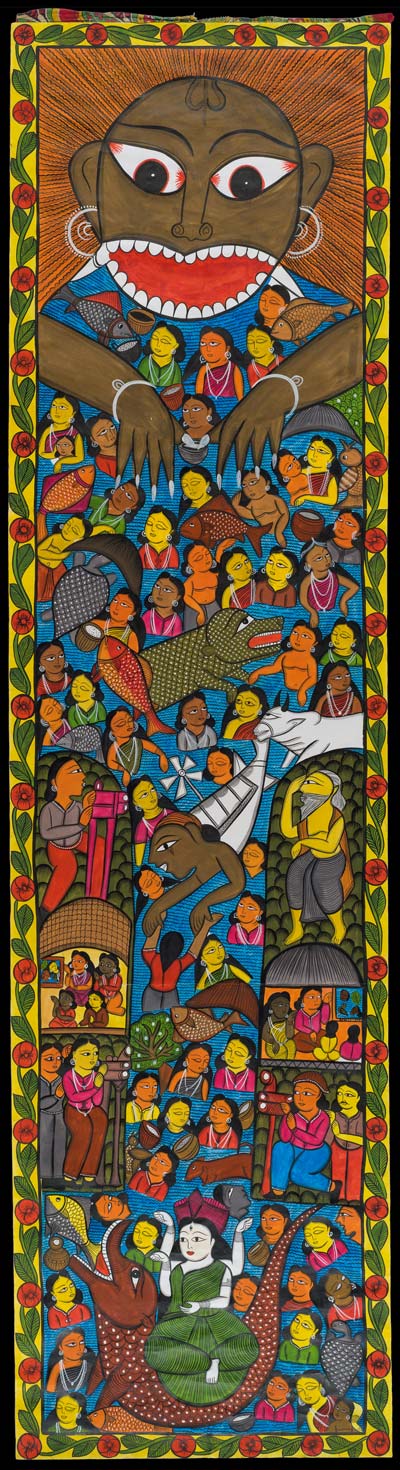

Eight years later, Colgate professors on a faculty development trip to India stopped in the Delhi Craft Museum, where a 7-foot–tall scroll depicting the tsunami caught their attention. Its creator, Momi Chitrakar, performed for them a mournful song about the painting. The moment sparked a lively, on-the-spot exchange among the professors, who shared their own academic perspectives on the tsunami and the art it inspired. They decided to buy the scroll and brought it back to campus, where they began passing it around for further discussion in classrooms and at professional conferences.

This past January, thanks to art and art history professor Liz Marlowe and support from the Teagle Foundation (see sidebar), the scroll took up residence in Case Library, in a specially built case. As part of the display, Marlowe also reignited the conversation that began in the Delhi museum by inviting professors from around campus to write mini-commentaries from the perspective of their disciplines. “Powerful objects like the tsunami scroll can pull people together in shared wonderment, curiosity, and inspiration,” Marlowe said.

— Aleta Mayne

Christian DuComb, theater

Like the script of a play, the scroll shapes but does not entirely determine the performance, which depends as much upon the singer’s voice as upon the painting itself.

By unrolling, holding, and pointing to the scroll as she sings, Momi offers her audience an aural and gestural interpretation of the imagery. Together, the words, the painting, and the singer’s voice and actions create a multisensory performance of the trauma wrought by the tsunami.

Padma Kaimal, art and art history

The vertical layout of the scroll presents a coherent visual narrative of an incomprehensible tragedy.

At the top, a frightening deity with red eyes, fangs, and a gaping mouth personifies the tsunami itself. Halfway down the scroll, a helicopter lifts a woman from the water. The helicopter’s front half takes on a human form, a magical hybrid accomplishing a miraculous rescue. To the right, a bearded, holy ascetic touches his forehead in wonderment at the sight. Television cameras operated by two women on the left, two men on the right, flank the scene. Families at home watch the disaster unfold on their TVs. Those who die in the water join the goddess at the bottom of the scroll. The vertical third eye in her forehead marks her connection to Shiva, a god who governs the cycle of life, from life to death and rebirth.

Maureen Hays-Mitchell, geography

The 2004 tsunami left a gendered landscape of disaster in its wake.

All across the Indian Ocean, the death toll among women far exceeded that of men, as this painting accurately reflects. In many regions, women were less likely to know how to swim or climb a tree. Flowing dresses hindered rapid flight. In southeast India, December 26 was a festival day. Crowds of women brought offerings of food and flowers to the seaside. When the water suddenly retreated, many women and children rushed out onto the exposed sands to see the surprises the water had left behind. When the wave returned, it swept them and their bowls of offerings — also depicted in the painting — out to sea.

Naomi Rood, classics

Momi Chitrakar’s practices and philosophical questions have much in common with those of ancient bards such as Homer.

Both traveled around to religious festivals. Both adapted traditional songs, making modern notions of authorship and originality inappropriate lenses through which to view their work. Both seek to make meaning in the aftermath of chaos and catastrophe in order to preserve and shape cultural memory, and to explore human relations with the gods. Both ask what it means to be mortal.

Joel Bordeaux, religion

Scroll paintings are typically connected to medieval storytelling traditions.

They served as visual aids during lengthy recitations of folk epics at temples and festivals. They often told stories about local deities who caused natural disasters to get people’s attention and spur them to worship.

Karen Harpp, geology

This scroll and song are a cultural form of scientific record.

Details like the “break in the ground” and the painting’s squiggly lines radiating outward from the god’s head accurately capture the tsunami’s cause — the shockwaves that radiated out from a major earthquake on the Indian Ocean floor. Geologists have only recently begun to realize the wealth of information that can be learned from ancestral stories, songs, and artwork about natural disasters, the largest and most dangerous of which may only occur at intervals of hundreds or thousands of years. Fortunately, people have been preserving information about natural disasters since long before the first geologist tied her hiking boots.

Liz Marlowe, museum studies

Powerful objects like the tsunami scroll can pull people together in shared wonderment, curiosity, and inspiration.

The insights offered here reflect extended conversations we’ve had in front of the painting, both in India and on campus. These conversations were greatly enriched by the diversity of our perspectives and ways of knowing. This display thus celebrates the fruitfulness of intellectual inquiry across disciplines, a central tenet of the liberal arts.

This project was generously sponsored by President Brian Casey and by the Teagle Foundation.

Crossing disciplinary boundaries

Installing the scroll in Case Library was Colgate’s first object- and exhibition-based teaching initiative funded by the Teagle Foundation. The three-year grant also supports parallel programs at Skidmore College, Hamilton College, and SUNY Albany. Each college rotates its faculty coordinator every semester, creating new exhibitions and projects for that term. Professor Liz Marlowe launched Colgate’s program in the fall of 2016. The scroll exemplified “the idea of an object standing at the intersection of multiple ways of knowing, multiple ways of thinking,” she said. “It’s the kind of thing that can bring us together across those disciplinary boundaries.”

Read more about the professors’ trip.

Additional faculty write-ups:

Connie Harsh, Dean of the Faculty

India was chosen as the destination of the 2012 faculty development trip for the many ways it spoke to all four Core components. As the world’s largest democracy and a nation with a rich history and unique model of modernization, it is poised to become an economic leader in the twenty-first century. Its propensity for cultural and religious syncretism provides an instructive example of moving beyond rigid boundaries. Its embrace of technology and its active confrontation of environmental issues show how science and society can intersect. Many of these themes are present in the faculty perspectives on the tsunami scroll.

Patricia Jue, Chemistry

Traditionally, painted scrolls were stored rolled up, and only unfurled during performances at religious festivals. The painted paper was glued onto recycled sari cloth. This provided durability, allowing the scroll to be rolled and unrolled without tearing. The paints were made from plant materials – red from betel leaf, yellow from turmeric, and so on. Because our scroll was created not for performances but for tourists, who might hang it on a wall, some of these traditional practices have been adapted. Unlike vegetable dyes, synthetic colorants won’t fade when exposed to light – and also allow for the brilliant hues of the blue water and hot pink saris we see here. But the use of sari-cloth backing has been preserved. A bit of it is visible along the scroll’s upper edge.

Navine Murshid, Political Science

At the NGO-run shop at the Delhi Craft Museum, our attention was drawn to the display of a dozen brightly painted, unfurled scrolls. Following our gaze, the artist-vendor sang snatches of the songs they illustrated – about 9/11, the Titanic, and the battles of the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata. When we settled on the tsunami scroll, she let us record her performance of the mournful song commemorating that tragedy. As a political scientist, what I see is how Momi Chitrakar had to commodify herself and “sell” her culture in order to make a living. I see how NGOs participate in the commodification and marketization of rural women. I am conscious of how by buying the scroll and displaying it for wider consumption, we in the “West” are not only consumers but have laid a certain claim to ownership.

Lesleigh Cushing, Jewish Studies

This painted scroll shares interesting traits with the Hebrew Bible. Although we encounter it as a printed book in Core 151 Legacies of the Ancient World, in synagogue settings, the Torah is inscribed on a scroll, which is unrolled and recited aloud during the weekly Shabbat liturgy. The Torah begins with Genesis, the story of a God who opens his mouth and speaks the world into being. In the tsunami scroll before us, we find an image of a great open mouth and a stream not of creation but of watery destruction. This theme also features in Genesis; and like the tsunami scroll, the Noah story is also ultimately about regeneration.

Cat Cardelús, Biology

Nature can defend us from itself – if we let it. Coastal mangroves and wetlands absorb wave energy, reducing wave height, speed and damage. Coastal ecosystems also store carbon, enhance soil quality, and house innumerable animal species. In many regions of the Indian Ocean, however, shrimp farming and real estate development have reduced coastal wetlands. Their conservation won’t make any one person rich, but it will protect many lives and livelihoods. With storm intensity predicted to increase with global warming, conservation efforts are more critical than ever.

Meg Worley, writing & rhetoric

The structuring of time and space in this painting connects with the American comics tradition. While sequential events run from top to bottom, simultaneous ones — such as the suffering of the people and the attention of the journalists — are arranged horizontally, recalling comics panels. Comics depend upon cultural conventions and expectations to convey information in compressed space. So, for example, Bangladeshis understand immediately how gender is marked in this image, whereas Americans have to figure it out. Finally, comics are sometimes defined by the interaction of image and text, which reminds us of this artwork’s missing other half, the song which our scroll once accompanied.