Student-professor partnerships ask probing questions

Countless Possibilities. That’s what researchers expect when they propose a hypothesis and embark on the unknown. At Colgate, students are oftentimes the ones who are forming the questions, while their professors look over their shoulders — sometimes in the same room, sometimes virtually from a different country — to ensure that students stay on course.

The result is a rich experience that gives students independence and the chance to work as professionals — collaborating with authorities around the world and periodically getting their findings published in journals.

There are certainly times when the results are contradictory or inconclusive to the original hypothesis, but that’s OK — in fact, failures can be fortuitous.

“Failure is an integral part of worthy research,” noted Professor Roger Rowlett, who is the immediate past president of the Council on Undergraduate Research, a national organization. “My students’ ‘failures’ are often anomalies that wind up being discoveries worthy of publication and further exploration,” added Rowlett, the Gordon and Dorothy Kline Professor of chemistry, who has supervised more than 100 students’ research. “Although it’s self-affirming to confirm one’s initial ideas, it’s often far more personally and professionally rewarding to have discovered something unexpected after successfully defeating challenges along the way.

“As Louis Pasteur famously said, ‘Chance favors the prepared mind.’ Undergraduate research prepares young minds,” he added.

So, join us — no lab coat required — as we observe recent projects that attempt to answer the unanswered.

Some early birds might steal the worm

CHEATING AND RISKY BEHAVIOR ARE INFLUENCED BY PEOPLE’S CIRCADIAN CLOCKS.

When’s the best time of day to make decisions? That can depend on whether you’re a night owl or an early bird.

Psychological factors aren’t the only part of our behavioral equation. Biology can also influence why we do what we do. A Colgate group has taken a closer look at this, specifically people’s ethical decision making and risk taking as it relates to our sleep cycles.

The findings were recently published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, in an article by Professor Krista Ingram (biology), Professor Ahmet Ay (biology and mathematics), Soo Bin Kwon ’16, Angela Escobar ’15, Molly Gordon ’15, and their collaborators.

Our circadian clocks — a set of genes involved in our internal rhythm — help determine our sleep cycle and affect alertness during the day. “There’s a master clock in our brains, but we also have clocks in our kidneys, livers, and skin that also keep time,” Ingram explained. There’s even a “hair clock,” which is how the researchers were able to noninvasively track their subjects’ internal rhythms by obtaining RNA samples from hair follicles.

“Not only is their circadian rhythm not at its peak in the afternoon, but also, their homeostatic energy — the pool of energy individuals have when they wake up in the morning — is depleted as they go through the day.” — Professor Krista Ingram

With the help of Professor Ay, Kwon (a computer science major who is now pursuing her advanced degree in bioinformatics at UCLA) wrote a computer modeling program to track if the subjects’ RNA was cycling early or late. The subjects then took an ethics test and a risk-taking measurement at various times of day.

The researchers found that, “on average, larks [morning people] are more likely to make unethical or risky decisions in the afternoon,” Ingram said. “Not only is their circadian rhythm not at its peak in the afternoon, but also, their homeostatic energy — the pool of energy individuals have when they wake up in the morning — is depleted as they go through the day.”

The same can be said about night owls making riskier and less-ethical decisions in the morning, but the correlation isn’t as strong, according to the team’s research. The reason being, while night owls aren’t at their circadian peak in the morning, they still have more energy at that time than larks who run out of steam at 3 p.m.

Having just wrapped up their two-year grant from Colgate’s Picker Interdisciplinary Science Institute, the team is still analyzing data and writing more papers on their findings.

Stay tuned. Next up: this group will explore how circadian rhythms affect athletes’ academic and athletic performance.

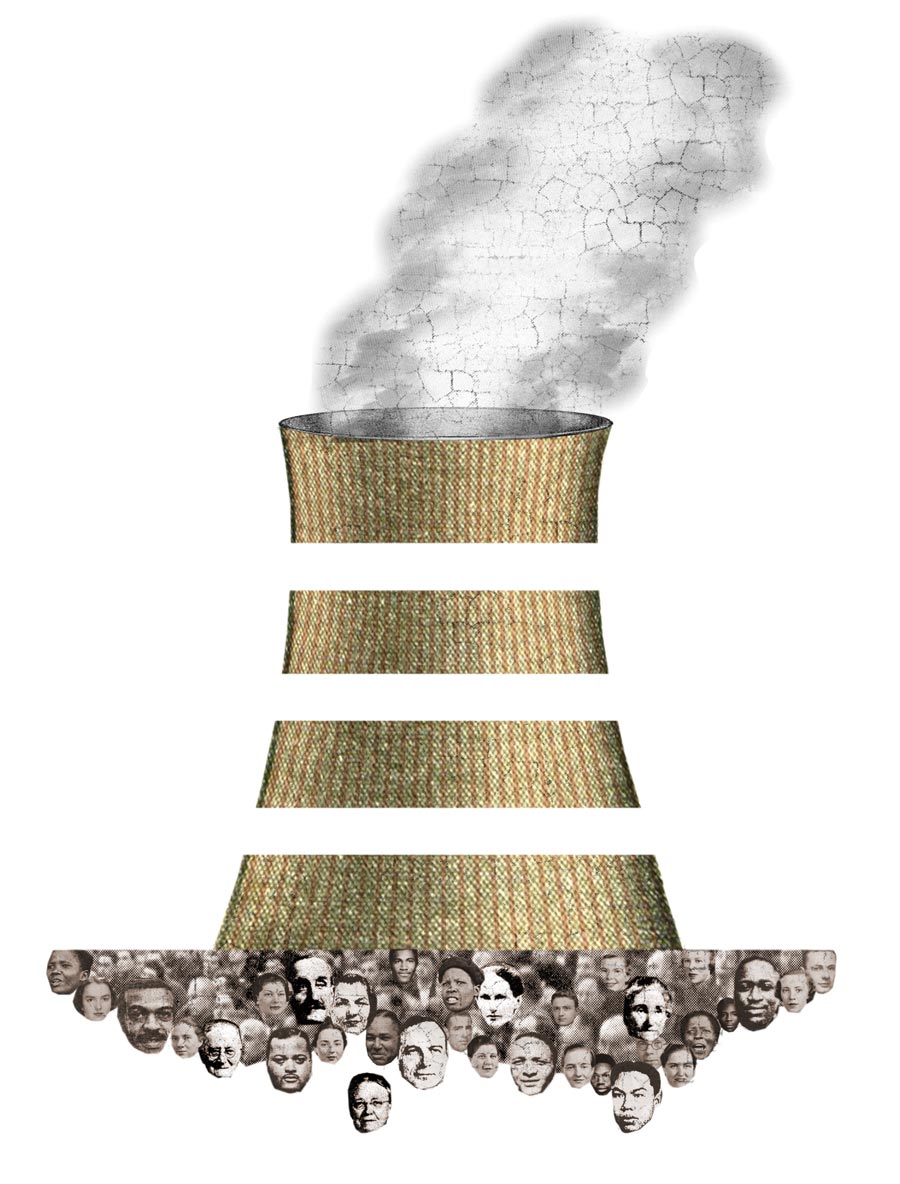

Power outage

OBSERVING THE POTENTIAL IMPACT OF NUCLEAR DECOMMISSIONING ON A COMMUNITY

With a research topic straight out of the headlines — the scheduled closure of the FitzPatrick Nuclear Power Plant in Scriba, N.Y. — Julia Feikens ’18 and Angelica Greco ’18 spent this past summer entrenched in that community. The pair’s goal was to examine the socioeconomic effects of the proposed nuclear plant decommissioning.

With a research topic straight out of the headlines — the scheduled closure of the FitzPatrick Nuclear Power Plant in Scriba, N.Y. — Julia Feikens ’18 and Angelica Greco ’18 spent this past summer entrenched in that community. The pair’s goal was to examine the socioeconomic effects of the proposed nuclear plant decommissioning.

Feikens had a previous summer’s experience of analyzing two closed New England plants as comparison. And the two students Skyped weekly with their adviser, Professor Daisaku Yamamoto (geography and Asian studies), who was on sabbatical in Japan.

Shouldering a weak economy that depends on the utility sector, Scriba and the surrounding area were predicted to reel from the plant closure, scheduled for January 2017. “It’s a big deal, especially because there are so many people who are unemployed and little income coming into the county,” said Feikens, who is majoring in environmental geography.

The reason behind the proposal to shutter the plant?

“It’s not profitable,” said Greco, a geography major. “The price of natural gas is so low. Because nuclear energy costs more [to make], the plant has been losing money.” The FitzPatrick plant, owned by Entergy Corp., isn’t an outlier in its fragility. “Overall, nuclear plants in the United States are disappearing,” she added.

“The price of natural gas is so low. Because nuclear energy costs more [to make], the plant has been losing money.” — Angelica Greco ’18

To get a fix on the potential impact, the pair combed through financials, including several years’ worth of school district budget plans. Their methodology also relied primarily on interviews with local players, including Scriba’s town supervisor, the school superintendent, members of the plant workers’ union, and people representing the energy company. To learn more about the environmental implications, the students spoke to renewable energy advocacy groups.

“We tried to talk to as many different stakeholders as possible,” said Greco, who also spent time studying the grassroots movement, called Upstate Energy Jobs Coalition, that was rallying around keeping the plant open.

Even though the school district in Mexico, N.Y., derives a significant portion of its support — $12 million or 23 percent — from plant taxes, Greco’s takeaway on the closure took her by surprise. “They seemed prepared for what could happen.”

There is a growing debate about whether nuclear power is a risk to the environment (potential accidents and nuclear waste disposal problems) or an environmental savior (low carbon emission during operation), according to Yamamoto. “Local viewpoints are often overlooked in these global discussions, and that’s what we’ve been trying to address,” he said.

For the moment, the debate is moot: On August 9, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that Exelon Corp., the owner of two other plants in the state, will purchase FitzPatrick and keep it open.

Although the students remained objective in their research, they also recognized the real impact on lives. “We’re glad that the people are feeling more relief economically, because it was obvious that they were struggling with that worry,” Feikens said.

Have microfossils, will time travel

TAKING A CENSUS OF WHAT’S BURIED DEEP IN THE OCEAN FLOOR IS HELPING TO CHART OUR FUTURE.

Each summer, Professor Amy Leventer returns to campus with samples from the bottom of the world.

Leventer, who has traveled to the Antarctic 23 times with a team of scientists, collects sediment core samples that are recovered from the seabed. Back on campus, her students study the fossilized microorganisms to reconstruct climate patterns dating from the recent past to 8 million years ago.

“These organisms are proxies for past climates and oceanic conditions,” said Kaylie Patacca ’17, an environmental geography major who is minoring in geology.

She and Meghan Duffy ’18 spent the summer carefully preparing slides from the core samples, slipping them under a microscope, and painstakingly counting unicellular algae — called diatoms — to look at how the ocean has changed over time.

“Learning things about these past climates can help us figure out how oceans might look in the future.” — Kaylie Patacca ’17

“You can tell how the patterns of each species have fluctuated,” said Duffy, a geology major. If there’s an abundance of a certain species that has a strong association with sea-ice presence or open-water conditions, “you can make inferences about what the oceanic conditions would have been like millions of years ago,” Patacca said.

The microfossils indicate changes in oceanic productivity, nutrient concentrations, light levels, and sea ice and glacial ice extent. “Learning things about these past climates can help us figure out how oceans might look in the future,” Patacca explained.

Meanwhile, Glenna Thomas ’17, an environmental geology major, catalogued and studied protozoa called radiolaria, with a similar goal. Because few people specialize in radiolaria (and Leventer isn’t one of them), Thomas has been consulting with scientists around the world. Patacca and Duffy, too, have been collaborating with U.S. scientists who have been helping with the analyses. In addition, for a paper that Leventer and the students are co-authoring, she is having colleagues around the country review their findings.

So, with funding from the National Science Foundation, this small group of students in Hamilton, N.Y., has had the opportunity to work with experienced scientists around the globe — and, most importantly, develop theories about the future of the world.

Attempting to settle the unsettled

WHY DO ANTIANXIETY AND ANTIDEPRESSANT MEDICATIONS WORK DIFFERENTLY FOR WOMEN VS. MEN?

It’s well known that women have higher rates of anxiety than men. But it’s also been proven that certain treatments work better for women than men, and vice versa. The reason why is a mystery. Professor Christina Ragan and her students set out to learn more.

It’s well known that women have higher rates of anxiety than men. But it’s also been proven that certain treatments work better for women than men, and vice versa. The reason why is a mystery. Professor Christina Ragan and her students set out to learn more.

“Women don’t respond well to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), whereas men’s symptoms of anxiety and depression subside,” Ragan said. “On the other hand, women will respond more favorably to a serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) like Prozac.”

Led by Ragan, Chris Higham ’18 and Jaime Ransohoff ’18 first tried to replicate the natural differences in anxiety with the sexes. Next, they wanted to figure out some of the underlying brain mechanisms that differ in males and females.

“We used a rodent model, because the biology is similar to humans,” Ragan explained. To test for baseline anxiety in the animals, the students used an elevated plus maze: a maze with two open arms and two closed arms that is raised off the ground. Like humans, rodents are innately fearful of open spaces, bright light, and height. The students observed the animals in the maze to gauge how long it took them to approach an open arm and how much time they spent there. Finding that the female rodents naturally spent more time in the closed arms than the males, “it was encouraging that we were able to replicate [the natural differences in anxiety],” Ragan said.

The animals were then divided into male and female groups. Those two groups were each divided into “acute” and “chronic” groups. Each animal in the acute groups received a single injection of either saline, a low dose of the TCA clomipramine, or a high dose of clomipramine. Meanwhile, the chronic groups were also divided into those three categories, but they each received one injection daily for three weeks (approximately the amount of time that it takes for TCAs to work in humans). On the last day of treatment, the students put the rodents into a second maze that was slightly different so that it would be a new testing environment.

“We found the opposite of what we expected,” Ragan said. Males that were given a low dose were significantly more anxious than the females in the same group. And animals in the high dose group, regardless of sex, exhibited more anxiety than the acute low and acute high dose groups.

The reasons for the unexpected outcomes could be many, the researchers explained. One possibility: the researchers didn’t induce anxiety in the animals, and the clomipramine could cause anxiety in animals that weren’t previously anxious. Also, the high dose may have been too high. “Which happens in humans, too — we sometimes have to optimize the dose that we give people,” Ragan said.

Chalking it up to the nature of the beast, Higham said, “I didn’t expect we’d be solving all the problems we set out to.” He added, “That’s what science is at its core: trying to find an answer to a question, and if that leads you to seven new questions, you have new directions to aim for.”

“That’s what science is at its core: trying to find an answer to a question, and if that leads you to seven new questions, you have new directions to aim for.” — Chris Higham ’18

This fall, the researchers are working on the next phase: studying the animals’ DNA methyltransferase 3a, a protein that is associated with anxiety. They’re also conducting a follow-up experiment by adding a group that receives treatment for seven days — to bridge the gap between one day and 21 days.

Looking beyond this semester, Higham, a cellular neuroscience major who has been involved in research since his first year at Colgate, has folded this continual pursuit of knowledge into his career plans. “I’ve always known that I want to be a doctor,” said the pre-med student whose Alumni Memorial Scholar grant helped fund this study. “But now I’m aiming for an MD/PhD, which would allow me to do research as well as be a practicing physician. It’s a lot of fun being able to develop a question and an experiment based on that question.”