REMEMBERING STEVEN J. RIGGS ’65

Dave Healey ’65 and Lee Woltman ’65 are looking toward the heavens. It’s dedication day, Oct. 1, 2016, at the Steven J. Riggs ’65 Rink, and although they’re watching the scoreboard, they could easily be in conversation with the long-departed hero for whom this stretch of ice is named. A quiet and competent, yet human, leader. A legend of North Country and Colgate Raider hockey, born on skates. The victim of a war synonymous with discord, incompetence, and waste.

Their eyes ask, “What do you think, Rigger?” There’s no answer, except for the roar of the crowd behind them.

The game of hockey might have changed radically in the 51 years since Steve Riggs earned his place in the Hall of Honor. Players skate faster, hit harder, and often have all their own teeth. But the sound of the fans is the same, and it can transport anyone back to the beginning of the story, once upon a time, when the world claimed to be simpler — and then, quite suddenly, became fatally complex.

Steven James Riggs was born on March 10, 1943. He was raised in Potsdam, N.Y., the land of mother, country, and apple pie; carved from the sandstone that surrounds the Raquette River. Solidly working class, fathers labored at Alcoa, Central Power and Light, the paper mill, the lumberyard, General Motors, or one of several universities in the area, including St. Lawrence, SUNY Potsdam, and Clarkson. Mothers might be stenographers or department store clerks, but they were more than likely at home.

Hockey was a pastime for some and a religion for most. “In the wintertime in Potsdam, you didn’t do anything but hockey — no one did. There’s nothing else to do,” said Steve’s older brother, Bill Riggs.

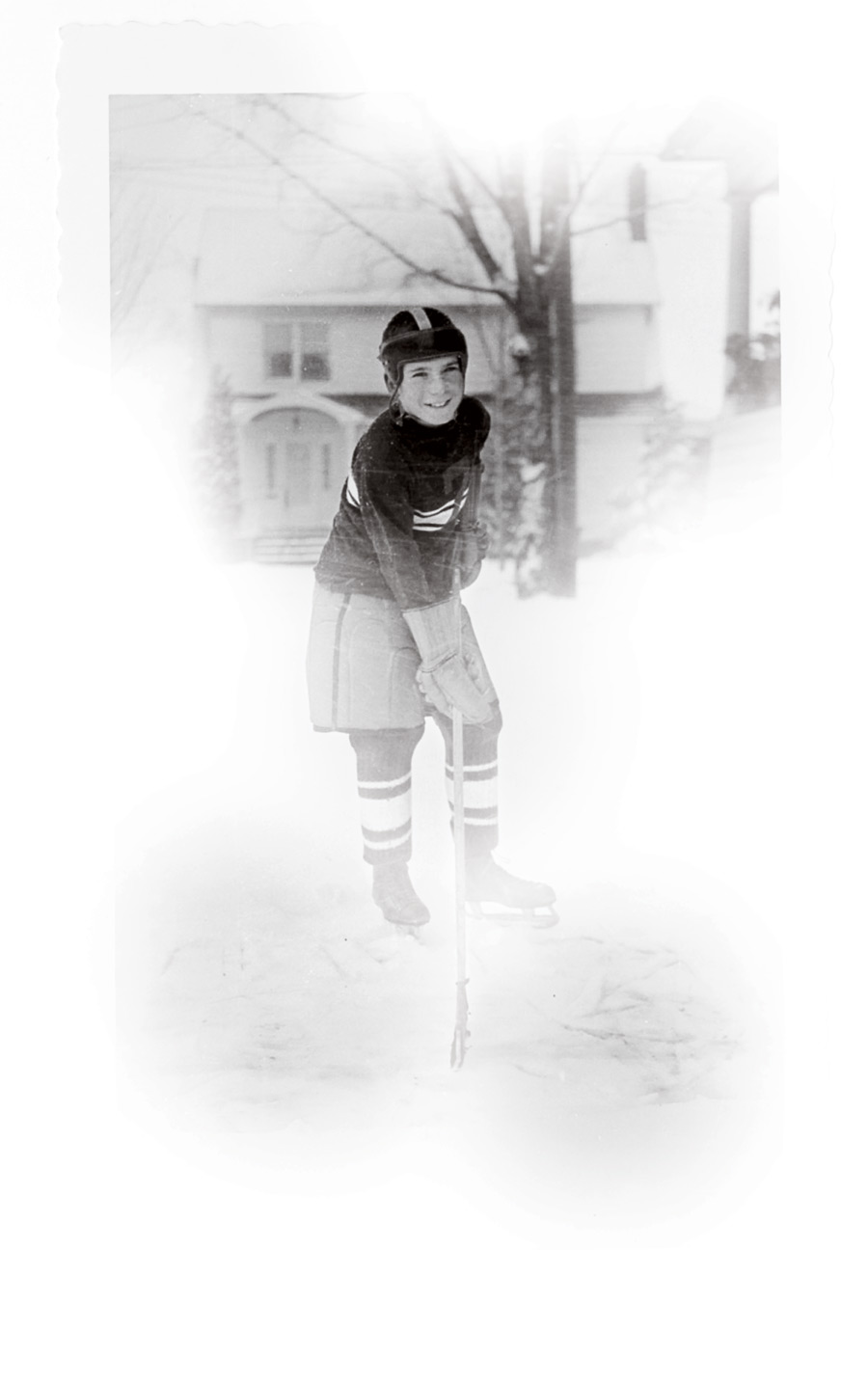

When Riggs was old enough to strap on skates, he played in the backyard on a homemade rink. At 9 years old, he hiked through the snowbanks to the Clarkson University arena for peewee training. He was picked for a traveling team at age 10, hoping that, after years of driving up and down the Northern Tier, he would play for the Potsdam Sandstoners’ high school squad. When he wasn’t playing, he watched college games at St. Lawrence and Clarkson. Between hockey seasons, there was baseball at the high school playground, tennis, and swimming at the local beach.

When Riggs was old enough to strap on skates, he played in the backyard on a homemade rink. At 9 years old, he hiked through the snowbanks to the Clarkson University arena for peewee training. He was picked for a traveling team at age 10, hoping that, after years of driving up and down the Northern Tier, he would play for the Potsdam Sandstoners’ high school squad. When he wasn’t playing, he watched college games at St. Lawrence and Clarkson. Between hockey seasons, there was baseball at the high school playground, tennis, and swimming at the local beach.

“In the wintertime in Potsdam, you didn’t do anything but hockey.” — Steve’s older brother, Bill Riggs

The second son of Wm. Frank Riggs, a local oil and gas company owner, Riggs was Potsdam’s golden boy. He started making the newspaper headlines for his sports prowess in the fourth grade. A small paragraph in the paper on July 5, 1956, simply reads, “Opening game of the Senior League in PeeWee baseball Monday night provided an oddity. Steve Riggs, pitching for the victorious Yankees, gave up a home run to Pinky Ryan, first man to bat for the Indians. It was the last hit the Indians got in the game.”

That reputation came with an attitude. Bill remembers his little brother as a 9-year-old hockey goalie, protecting the net against an opposing team of neighborhood friends on the backyard rink in the dead of winter. One of those friends made the mistake of scoring. Young Riggs, already a three-year veteran on the ice at 10 State Street and unable to contain his rage, skated up behind him, grabbed his collar, and ripped the sweater off of his back.

Over time, Bill said, the rage settled down and converted itself into an intensity, on and off the ice, that would become a hallmark of Riggs’s personality.

Proximity to Clarkson and St. Lawrence universities meant that Riggs had access to some of the greatest coaches in the country. Joe Thompson from the undefeated 1956 Clarkson hockey team lived in the Riggs home and played with the youngest family member in the rare moments when he wasn’t studying or practicing. All-Americans like Bill Sloan from St. Lawrence and Jack Porter from Clarkson helped train Riggs in his formative years with the Sandstoners. “He absorbed it,” said Dave Healey ’65, a fellow rink rat who moved to Potsdam just as Riggs’s name was beginning to appear in the sports pages of the newspaper. “He was an ideal student, because he had the skill sets and the ability, and he was easy to work with.”

— Dave Healey ’65

During his junior year at Potsdam High, Riggs and fellow Sandstoners John Fiske and Marty Manley became known as the Fabulous Three and were the first full line to be named to the All-Northern Class A Hockey Team. Riggs was elected captain for his senior season, and the team went undefeated until the last game of the Clarkson Invitational Tournament, when they lost by two points to fierce rival Canton. Off the ice, Riggs’s leadership was also well established. He was elected class president his last three years at Potsdam High and student body president as a senior. In addition to captaining the hockey team, he also led the school’s 1960 football squad.

It’s tempting to think that Riggs might have been the kind of leader who gave a rousing pre-game speech. But that wasn’t the case. “He wasn’t talkative or inspirational in a vocal sense,” Healey said. “He was there with purpose and commitment, and he was somebody you didn’t want to disappoint.” Riggs led by example rather than exhortation, even in his earliest days. That approach would only become stronger as he took on more responsibility.

Riggs had plenty to say one spring afternoon when Clarkson head hockey coach Len Ceglarski dropped by the Riggs family’s house. Steve, Bill, and Frank were planting the lawn, and Ceglarski had a captive audience as he talked hockey while sitting on the front porch. According to Bill, as Ceglarski wrapped up his visit and walked toward his car, he turned and said, “Steve, you know, if you want to come to Clarkson, it’s all free.” When the coach’s car cleared the curb, Frank said, “Well, you know where you’re going to college.”

But Riggs had met head Colgate hockey coach Olav Kollevoll ’45 and freshman team hockey coach Howard Starr. “Steve worshipped Howie Starr,” Bill said. “He thought he was the Lord God Almighty.” So when it came to a choice between a full-ride scholarship across the street and the opportunity to play in heaven, the answer was obvious.

“And that was the end of that,” Bill said.

Steve Riggs arrived in Hamilton at the beginning of September 1961, and the points started rolling in on December 2. At that time, first-year students couldn’t play varsity, so Riggs and Healey joined the freshman team, coached by Starr. In their premiere game against Rochester, Riggs scored the first goal unassisted and followed up with three more before the final buzzer. Rochester lost 11–1.

— BOB MEEHAN ’65

Graduating to the varsity team in the 1962–63 season, he launched a 72-game career and logged 123 points — 51 goals and 72 assists. He played 65 fewer games than today’s varsity hockey athletes, yet he remains on the top-25 list of all-time Colgate hockey goal scorers, one of only three from that era to secure such an accomplishment. If today a hockey-stats nerd were to play out average points per game for an additional 65 contests, Riggs would still be securely placed at the top of the scoring pantheon, where he originally finished in 1965.

Competing against Riggs was no pleasure. He had a hard, accurate shot that could light the lamp from the blue line and concuss a goalie who wasn’t quick enough to evade the puck. He was a fast skater who knew how to protect himself. “Wherever you wanted to go to hit him, he wouldn’t be there when you got there,” Healey said. When he took to the ice, his eyes grew wide — so wide that, a half-century later, his teammates still mention them first if they’re asked about Riggs’s leading characteristics as a hall of famer. “They never blinked,” Bob Meehan ’65 said.

Riggs was elected captain during his final year at Colgate, again leading by example rather than words. “Sometimes, between periods, he would say nothing,” Meehan remembered. “And it was seldom he said anything before the game, but on the ice, he was on fire.”

And those who weren’t as fiery? “He never made judgments or looked down on that in any way,” Healey said. “As long as you were trying as hard as you could,” he added.

Riggs still holds one Colgate hockey record: the most goals scored in less than a minute. It happened, of all places, back in that old Clarkson University rink, during his senior year.

Colgate VS. Cornell, March, 1964

It hovered just below freezing inside the arena on the evening of Friday, Dec. 11, 1964, but a capacity crowd of nearly 2,000 fans was far from frigid as the Raiders and the Golden Knights took to the ice.

Riggs, Healey, and the rest of the team had been in town since the evening before. Riggs had spent the night in his own bed; the rest of the squad bunked at a local hotel. If Carolyn Riggs had hoped to spend time with her son and maybe have lunch together on Main Street, she was sorely disappointed. Riggs spent the majority of the day sitting in the family’s living room, staring into space, lacing and relacing his skates. “It’s hard to break a pair of new hockey laces,” brother Bill said, “but Steve went through three pairs that day, just tying and untying them.”

The roar that greeted Riggs as he skated out in front of the crowd proved why preparation was so important. Although it was an away game, the men, women, and children packing the four tiers of wooden benchwork were cheering as much for him and for Healey as they were for Clarkson. Some, including Clarkson coach Ceglarski, would say they were screaming more for the away team.

“Steve just had an instinct for where to be.” — Dave Healey ’65

The game began well for the Raiders. After only 52 seconds of play, Healey fed the puck to Barry Tait, who put it into the net to draw first blood. But, after two periods, Clarkson had redressed the balance and upped the ante, and the score was 3–2.

During the break, they took a quick drink, heard a word from Kollevoll, and fully realized that they were losing, even though Healey’s little wool-wrapped siblings were banging their pots and pans so loudly, they were told to quiet down or leave the building. The Zamboni did its work. Then the Raider six were back on the center line, and the clock started its final countdown from 20:00. Riggs’s skates, so carefully tied, cut back and forth across the smoothed ice trying to find an opening in the Golden Knights’ sdefenses.

Healey’s job was to work the corners — the dangerous hinterland of the rink where unprotected faces could be mashed against wire-mesh netting with terrible consequences — and feed the puck to Riggs for a shot on goal. “I was on the left wing,” Healey said. “Steve just had an instinct for where to be.” At 14:35, Riggs received Healey’s pass and sunk the puck in the back of the net. The crowd went wild, the team returned to the center line, and the whistle blew.

Riggs was in the right place again.

And again.

In 59 seconds, Riggs scored a hat trick against one of the top teams in the league. The ceiling shook, the floorboards rang, and the lead held. Clarkson managed one more goal at 5:25 but, in spite of the 46 shots they aimed at Colgate goalie Casey Knobel ’65 that night, they couldn’t make a comeback. The final score was 5–4. In the locker room after the game, Rigger gave Healey a bear hug and, with a smile, simply said, “We did it.” And that was the last time that the Potsdam crowd would see him do it, the last time the sound of his powerful shot would ring off the walls of Clarkson Arena — his true home ice since age 9.

Goals came more easily than grades for the psychology major. Those who knew him best remember Riggs as someone who had to work hard to keep his balance in the classroom. According to teammate Win Guilmette ’65, Riggs chose his fraternity, Phi Delta Theta, because the house was more studious and disciplined than some others, and Riggs spent his spare time at his desk rather than at Hickey’s bar.

“Steve was never a big party guy,” Healey said. “You had to encourage him to come along, and then he would always be one of the more sane or moderate influences.” For all of his hard work and moderation, Riggs would just scrape the GPA required to earn his degree. But earn it he did. He received his diploma in 1965 from President Barnett, shook his hand, and said a quick goodbye to his friends and classmates. Then he headed home to Potsdam.

Riggs kept busy in the year after graduation. He took courses toward a master’s degree in education at St. Lawrence University. He coached his former rival, Canton High, to a 14–2 record that included the Northern League and Clarkson Tournament championships. And he continued to make local headlines by playing for the New York Rangers farm team, the Lake Placid Roamers.

The safe world of the Northern Country spun as it ever did. But the rest of the globe was far less tranquil. While Riggs was teaching teens how to scoop the puck between skate and stick, President Lyndon Johnson was increasing military draft numbers to more than 35,000 men per month, and personnel levels in Southeast Asia were rising to more than 385,000. As Riggs played his final game with the Roamers, the 3rd Marine Amphibious Force and other elements operating as Task Force Oregon were on their way to leveling 70 percent of the houses in a particularly contentious portion of South Vietnam called Quang Ngai Province.

The summer of 1966 was so peaceful in Potsdam, though, Riggs joined the volunteer fire squad for excitement. Only weeks later, he was invited by the U.S. Government to become a public servant of another kind, and the lull was over. The draft had found him. From September to November he was in basic training at Fort Dix, where he received an early promotion to private, thanks to his excellent physical condition and his aim with a rifle. Then he was off to infantry officer’s training at Fort Benning, Ga.

Riggs was always physically fit, and confidence was a part of his bearing even before entering the service. But friends did notice a change. Riggs visited Guilmette on a weekend pass, and his classmate saw that “he was more edgy, more intense.”

This changed Riggs was sent to the 46th Direct Support Group at Ft. Devens, Mass. He became the fort’s athletic director and an anchor of the post’s new hockey team. In the early days of fall 1967, he received a call from Colgate Athletic Director Everett “Eppy” Barnes ’22,asking if he’d like to try out for the 1968 National Hockey Team and represent his country in the Olympics. The army helped out by granting him leave to head an hour north to Framingham, Mass., where he spent a week dusting off his skills.

Meehan, by then a first lieutenant in the Air Force, also received the call and met up with Riggs on the ice for the first time in more than two years. They skated hard against competition from the East and the Midwest, and on the last day of tryouts, Coach Murray Williamson cut both Raiders. “We sat on the steps outside the rink,” Meehan remembered. “Steve said, ‘I know I’m going to Vietnam.’”

After losing out on his Olympic bid, Riggs was invited out to a movie with his Ft. Devens’s hockey buddy Leo Gould and a bunch of friends. It was Thursday, Oct. 12, 1967, and Leo’s wife, Judy, invited her cousin Janet Deschenes to come along. Only later did Janet realize that, while the evening was pitched as a group outing, it was actually a setup. “Steve and I paired up really fast,” Janet said with a laugh. “I guess we had an attraction. He was very handsome, very humble, very quiet. I probably did most of the talking.”

One date led to another. Janet, who knew nothing about hockey, started to appear in the stands at Ft. Devens matches. “I’d ask, ‘How come you’re down there and everyone else is back there?’ He’d smile and say, ‘Well, they just haven’t caught up yet.’”

The instant attraction grew into a deep connection. She learned to read Steve’s eyes (“chocolate brown”) for information about how he was feeling rather than waiting an eternity for him to say something. She could see his growing love there, and she could see when he was angry, worried, or jealous. Somewhere inside, that fierce 9-year-old goalie still lurked, and Janet caught glimpses — when she told Steve at the beginning of their relationship that she had previously made a date with another man and felt like she had to keep it, or when she loaned her car to a male friend, thinking it was no big deal. “He was very jealous. You knew when he was mad. You knew the look. He’d shut down, and it was definitely quiet time, but I never heard him raise his voice.”

“He was a man who always wanted to do the right thing.” — Janet Riggs

March 19, 1968, was Janet’s birthday, and Riggs didn’t bother with the teddy bear or flowers for a present. Although he and Janet had only been dating for five months, he opted for an engagement ring, and they set a wedding date for July 4, 1968. Worried that Janet’s Catholic family wouldn’t permit her to marry a Protestant, or that she wouldn’t be allowed to be married in the church in which she grew up, Riggs started taking classes to convert to Catholicism at Ft. Devens. “He was a man who always wanted to do the right thing, and he totally loved me,” Janet said. “He didn’t want anything to go wrong.”

Ecstatic to be engaged, the couple traveled to Potsdam to make introductions, and they stayed a week. They returned Sunday night, and Monday Riggs went to work as usual. Unusually, he called Janet before lunch and told her that he was coming to take her to their favorite restaurant and then to the mall for a shopping trip. While she thought that was odd, she chose to enjoy the outing. That night, the cousins descended on Leo and Judy’s place for dinner. Janet chatted happily about wedding preparations, but there was a dark mood in the house. No one was joining her in the enthusiasm. When she expressed her exasperation, Riggs took her by the arm, led her into a bedroom, and told her that he had just received orders to deploy to Vietnam.

Riggs was well aware that Janet’s brother, Specialist Fourth Class Thomas Deschenes, had been killed on June 22, 1967, just four months before the couple met. Riggs was ready for the response that his news would bring and the wounds it would reopen for the entire Deschenes family, but could think of no other way to soften the blow than with a special lunch and the purchase of a new dress. His brave attempt failed miserably. “I went totally hysterical,” Janet said. “Steve was just quiet — totally quiet — there was no talking.”

Physically ill and in an emotional tailspin, Janet took her fiancé to visit the family priest. “He calmed me down,” Janet said. “He said, ‘I know Steve is coming back, and it’s only going to be for a year.'” He also convinced the couple to marry immediately rather than waiting for the end of Riggs’s tour of duty. The wedding was rescheduled for April 6, less than six months after the couple first met. To Janet, it was the miracle wedding. She borrowed pink silk bridesmaids dresses from a friend who had recently wed, and they fit her wedding party without any alterations. The Riggs family appeared in Massachusetts and Bill served as his brother’s best man.

For three months, Mr. and Mrs. Riggs made a home together in a Fitchburg, Mass., apartment, although they spent most of that time traveling. They honeymooned in Bermuda (where Steve, ever the volunteer firefighter, became a local hero by putting out a midnight fire in the hotel kitchens). They spent several weeks in Potsdam with Frank, Carolyn, and Bill. Then they flew to San Francisco for a week. On July 4, the day they had originally intended to marry, Janet flew east, back to her parents’ house, to resume her job styling hair at a local salon. Second Lieutenant Riggs flew west to LZ Liz in Quang Ngai Province, known among soldiers as a hotbed of malaria, mud, and Vietcong guerillas.

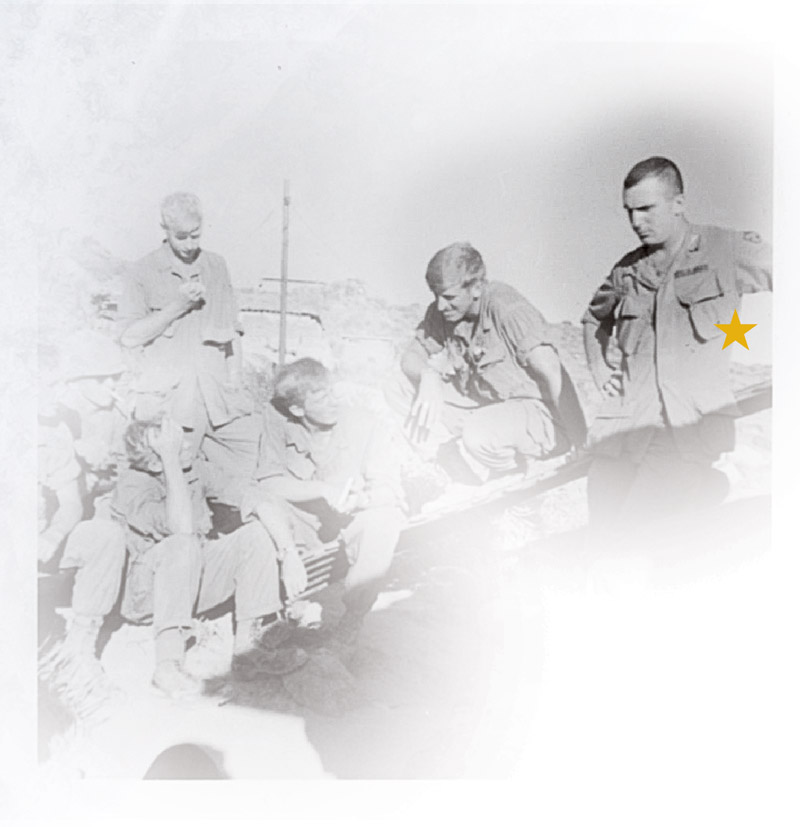

Riggs reported to the headquarters of the Americal Division and assumed command of Second Platoon, Bravo Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry (a.k.a. Sykes Regulars) on July 7, 1968. Americal had taken over where Task Force Oregon left off, and Riggs was at a disadvantage. While he had been earning his gold bar in Georgia and starting a hockey team in Massachusetts, the 1/20th had been training at the Jungle Guerrilla Warfare Training Center at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii. Yet they expected him to live up to the Sykes motto and fight with them: “Tant que je puis/To the limit of our ability.”

In spite of being in charge of 30 men, Riggs still found time to write regularly to his wife, the rest of his family, and some of his old Colgate classmates. To Janet, he wrote about plans for their apartment in Fitchburg, whether to buy a new cartridge-style cassette player, a reel-to-reel system, or a turntable. He checked to make sure she’d paid the rent and the credit bill at the gas station. He sent her a picture of a Vietcong prisoner who spent the night tied up in his hut. He outlined the basic way they spent their weeks, sending out ambush parties at night and occupying local huts for sleeping quarters during the day. “Every day is the same,” he wrote. “The easiest way to tell what day it is: every Monday, the medic gives us our malaria pills. Otherwise, we would have no conception of the day of the week.”

Her letters kept him going, and the snapshots she enclosed lifted his spirits. “I know that this separation is causing you plenty of grief and pain,” he wrote in return. “I’m going to make it up to you.”

A month after deploying, Riggs received a letter from Janet. On the envelope, she had written “IMPORTANT.” This is how a husband found out that he was also to be a father. The initial reaction was far from positive. It was unplanned, and he wasn’t there to help her through the process — to carry out his responsibilities. In letter after letter during the remaining days of August, he tried to pedal back from his first words of surprise and dismay. On August 19, he wrote, “I am with you 200 percent.” On August 20, he reminded her that, “I hope my first letters about your pregnancy have been forgotten. It was my first reaction, and I just couldn’t hold it back. I’m becoming as excited as you are.” He suggested a name for the baby: Thomas William Riggs.

In spite of being in charge of 30 men, Riggs still found time to write regularly…

Meanwhile, when he wasn’t using his pen, he was carrying his rifle through rivers and streams, sleeping naked to find relief from clothes made wet by the jungle humidity. Warm food was a luxury, tinned rations the norm. Riggs and his men were often relieved to leave the supposed safety of their base camp and wander into booby-trapped rice paddies. At base camp, on the high ground and surrounded by perimeter wire, they were tempted to relax. But they were prey for snipers who took regular potshots through the gates. “We were shot at all times of day and night,” said Keith Kolozie, a sergeant and radioman in Riggs’s platoon. On patrol, at least they were on guard, always expecting an ambush.

Riggs earned his men’s trust in much the same way he earned the captaincy of his college hockey team. He never gave rousing speeches, never yelled or hectored his men for a lack of skill. Instead, he led from the front and by example, turning to seasoned sergeants for advice and engaging in the fighting himself. “If we were calling in a fire mission for air support and he wasn’t sure of the ordinance and the plot lines on the map, he would ask for assistance,” Kolozie said. “Unfortunately, some officers who elected to go it alone brought fire down right on their own heads.” His care and concern were noted by the brass, and he was promoted to first lieutenant while in the field. He didn’t wear the silver bar, because the Vietnamese aimed for officers first in a fight.

On August 25, Riggs wrote to Janet, saying, “It’s been two days since I’ve had a chance to write to you. There has been a change in our location, and we’ve been very busy getting settled.” He failed to mention that, in those two days, during that change of location, he also engaged in such fierce combat with the enemy that he earned his first bronze star for individual acts of heroism.

Second Platoon filed out through the base camp perimeter with the rest of Bravo Company on the afternoon of Sept. 3, 1968. In a constant nearsighted search for booby traps, they followed the sun west across Duc Pho District for four hours, the squelching mud of the rice paddies and the grit of unpaved roads sounding off beneath their steel-toed boots. Kolozie carried the radio and walked in front of Riggs. Behind the L.T. came Sgt. Joaquin Garcia. Behind them, past the bombed-out huts and defoliated treeline of Quy Thien, the South China Sea lapped at darkening beaches.

Photo by Keith Kolozie

As the humid day ended in Southeast Asia, it was dawning back home in Fitchburg, gray, cool, and foggy. Janet switched off her alarm clock, feeling for signs of movement in her belly. Time to get ready for a day cutting hair. On the other side of the world, Riggs worked the evening shift. He began to set up an ambush near a fork in the Song Ba Lien river, preparing to kill Vietcong — to prevent them from slipping into the caves and tunnels that were as much a feature of the landscape as the jagged stumps of hopea trees.

While Janet turned on the percolator in her parents’ kitchen, a squad of Vietcong detonated three mines under Second Platoon, and the ambushers were ambushed.

Garcia still remembers the flash. The bang. The sight of Kolozie, flung 25 feet into the air, a rag doll strapped to a radio. Riggs prone on the ground. “I just remember thinking, ‘The L.T. is down. The L.T. is down,’” Garcia said, the confusion still audible in his voice after 47 years. “I’ll never forget the smell of blood and gunpowder as long as I live.”

Life continued, but not for First Lieutenant Steven J. Riggs. The 26-year-old newlywed, father-to-be, brother, son, hockey captain, soldier, classmate, friend was dead. It happened so quickly — after such a slow, long hike. Kolozie was standing directly on top of a mine when it exploded; the force launched him clear of the worst danger. Riggs, immediately behind him, absorbed the shrapnel, leaving Sgt. Garcia unscathed. “He was a shield,” Garcia said. “I would have caught all the frag.”

The explosion was followed by small-arms fire, which Garcia and other Americans returned with interest. Within two hours, Bravo Company tracked eight Vietcong to a hut near the coast and took revenge with a series of carefully placed grenades. “Anytime you killed any of our guys, it hurt,” Garcia said. “Once you started killing our brass…”

But vengeance couldn’t bring Riggs back to life, and it couldn’t keep Janet from feeling an unusually strong sensation of fear and apprehension as she fixed her hair. By the time she brushed away her foreboding and walked out the door for work, her husband’s body was being prepared to fly the first klicks of a long journey between two republics. The hometown boy made good again, but he couldn’t know that his last moment on earth was spent protecting a teammate. He would never rest his kind, competitive, chocolate-brown eyes on the story of his achievements in Potsdam’s Courier Freeman or pass off praise for his second bronze star with a quiet grin.

On Friday, Sept. 13, 1968, Riggs’s body lay in state at the Seymour Funeral Home in Potsdam. “I knew I had to take him home,” Janet said. The next day, under a clear sky, the community turned out in force to pay their respects at the funeral, presided over by a Protestant minister and a Catholic priest. Healey, who had severely fractured his leg during a softball game only weeks before, helped carry the casket while wearing a walking cast applied specifically for the event. Members of the Canton and Potsdam high school hockey teams sat together in the pews. A full honor guard drove in from Ft. Devens.

Eleven months after meeting Riggs on a blind date, five months after celebrating their marriage, Janet found herself in the middle of a very different sacrament. “I kept accidentally calling the funeral ‘the wedding,’” she said. The relationship that began with such fireworks ended with the crack of 21 guns.

When the class signed the beams that would go into the Class of 1965 Arena during their 50th Reunion, Steve put his — and his father’s — name on the steel.

The following spring, Janet gave birth to Steven T. Riggs. Within seven years, she remarried and had another son, Tom. Although she never thought she could leave her hometown and her family, she eventually moved to Florida where she lives today, a picture of her first husband and his 1965 Colgate hockey team on the wall of her Delray Beach condo.

When Steve T. was in high school, he met members of the Class of 1965, and they made him an honorary member of their cohort. Young Steve and Janet were there in 1990 when the class dedicated the hockey locker room in Reid Athletic Center in Riggs’s memory. When the class signed the beams that would go into the Class of 1965 Arena during their 50th Reunion, Steve put his — and his father’s — name on the steel.

Naming Colgate’s new rink after Riggs might seem counterintuitive, given his personality. This was, after all, a man who never spoke of his own accomplishments. He never lorded over those with less skill. He gloried in being a member of a team. But every team needs a captain. By doing his duty with quiet and uncommon skill, Riggs won the loyalty and admiration of his peers, and by displaying the spirit that is Colgate, he secured a place in the heart and soul of his campus.

In the decades to come, heads will tilt upward to read his name on the wall of the Class of 1965 Arena. “Riggs” will become synonymous with a Division I athletics program that punches hard above its weight on the field, the court, the rink, and in the classroom. When players and visitors discover who he was, how he lived, and how he died, Riggs will demonstrate more leadership by example. And although he never would have asked to become the symbol of the ethic he lived — the principles that ultimately cost him his life — no one can argue that he earned it.

View more information on the Class of 1965 Arena

Steve was a fine hockey player and a great man i loved him as a brother we played together at ft Devens and i was in his wedding hi son Steve is a chip off of the old block we had lots of fun together golfing and hockey one of our friends big Jim Lightfoot who keept us out of trouble those were the days i miss him dearly he was a hero