Manipulating their rakes differently at first and then in coordinated, graceful sweeps, four students performed Archive of Regional Raking on the 100 Broad Street lawn. Those passing by on that dusky Halloween eve probably wondered why a crowd was gathered round what normally constitutes a fall chore.

Photos by Andrew Daddio

The only sounds in the first act were leaves swishing, geese honking overhead, and cars driving by on Broad Street. Then, leaf blowers provided a drone effect. Lastly, rakes that were rigged with microphones produced a melodic soundtrack synthesized by the event’s orchestrator: artist Chris Kallmyer.

Kallmyer was one of 11 artists in residence during the two-month-long Perfect Strangers: Machine Project and the Hamiltonians. Together with the Colgate and Hamilton communities, these artists conducted experiments that facilitated discussions and posed philosophical questions, including: What is art?

Machine Project is a Los Angeles–based organization “that works with artists to develop new projects often involving performance or participation with the public,” explained founder Mark Allen. Its troupe has traveled the world, performing in various combinations and sites, but this fall was the organization’s first collaboration with a whole town.

Events ranged from interpretive dance, to protest songs, to intuition workshops. “Machine Project is part of a larger genre, which is sometimes called social practice,” said art and art history professor DeWitt Godfrey, who invited the group to Colgate. “Artists use the relationships between people or within communities as a kind of material — not just a setting, but actually how people interact with each other and what that says about who we are.”

Godfrey met Allen almost 10 years ago, through a program at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas. “I was really taken by his description of what he was doing with Machine Project,” Godfrey recalled. “It seemed to me that it would be an engaged public art happening that would be valuable for Colgate and our students, as a way of taking art out of the gallery into the community, to see how art works in that context.” This fall, the timing was right, and Godfrey’s department colleague Professor Lynn Schwarzer agreed to be a coordinator. Machine Project was supported by the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation Artists in Residence program.

Almost all of the projects were tailored specifically for Hamilton and Colgate. Allen invited artists whose work could be done outside of a studio and who he thought would connect with different audiences. “It’s like making a mixed tape,” Allen said. “You think about how one project moves into the next. You want transitions that are logical, but then you want real diverse ways of interacting.”

There was something for everyone, said Godfrey. “You’re not required to like it all. It’s like a concert hall in a particular season.”

Computing with the dead: In an homage to John Vincent Atanasoff, the inventor of the digital computer who was born in Hamilton, N.Y., Brian Crabtree and Kelli Cain spun an electromechanical installation using music and light. Photo by Zoe Zhong ’17

Defining the undefinable

A first-year seminar called Art in Community, taught by Godfrey, was organized around Machine Project’s visit. “We started with talking about what art is,” explained Ally Shahidi ’19. “[It’s difficult to try] to put a definition on something that’s completely undefinable. That’s what Machine Project is — they push the boundaries on where the definition of art is and what falls in and outside of that category.”

The class looked at historical studies, discussing how art has evolved over time, and used Machine Project as a case study — talking about how it fits.

“This thing we call art occupies an impossibly wide spectrum,” Godfrey emphasized. “We were really focused on the things that might not seem at first to be art, that don’t fit people’s regular criteria. If art is having a séance over experimental music at Merrill House, then what is a painting? What is a sculpture? It requires you to shift your categories.”

The 10 students were each paired with an artist (in one case, a collective of two artists), interviewing them about their work and helping as an assistant when needed. “We’re not just presenting culture — we’re helping to produce it,” Godfrey said.

Both as a participant and an observer, “you realize you’re being asked some very interesting, and maybe even profound, questions about how art can function,” Godfrey said. “What does art tell us about the world that other constructions of knowledge don’t?”

Signs, signs, everywhere there’s signs

Hanging in the windows of businesses around town, bold-colored logos were designed by Tiffanie Tran for the 40 storefronts that signed up. “How you bring a group of artists into a community, and have [both groups] feel as though it’s a mutual kind of greeting and exchange was an interesting process,” said Schwarzer. The signs represented that reciprocal welcome.

Photos by Lynn Schwarzer

An original duplicate

When Mercedes Teixido (pictured above) said she wanted to work in a library setting, Schwarzer asked Hamilton Public Library director Hilary Virgil to help welcome Machine Project.

Hosting several sessions throughout the building, Teixido listened to participants reading passages, or just talking, while she used a contraption to make artistic interpretations of what she was hearing. The apparatus was based on Thomas Jefferson’s polygraph machine, which he used to copy his letters. “[Jefferson] used it primarily to make duplicates,” Virgil explained, “but Mercedes takes it in a different direction entirely. She makes it an art form, using the spoken word.” The library was a natural setting because of the readily available reading materials.

At one of Teixido’s events, people lined up to participate. “Because the library works with such a diverse population, it was a great opportunity to make [Machine Project] widespread — introducing it to children, teens, adults, and elderly folks,” Virgil said.

In protest of the protest song

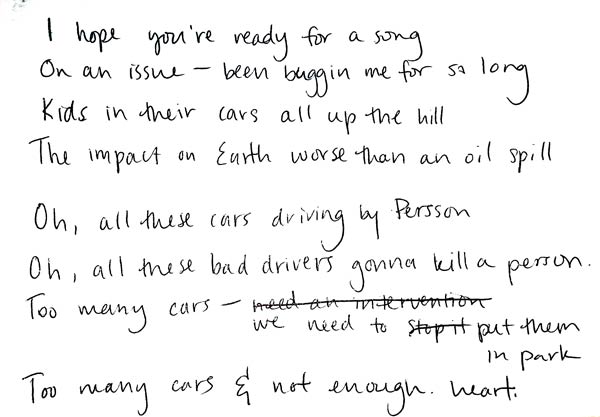

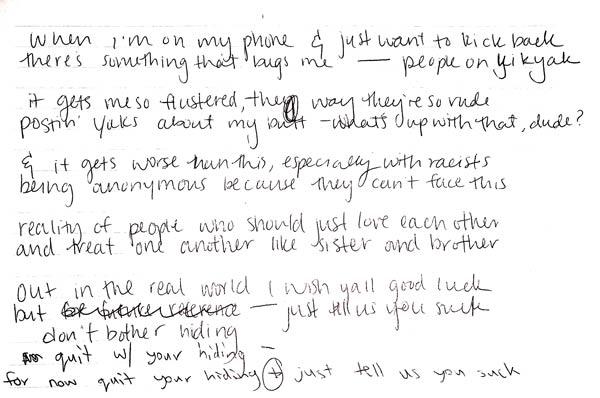

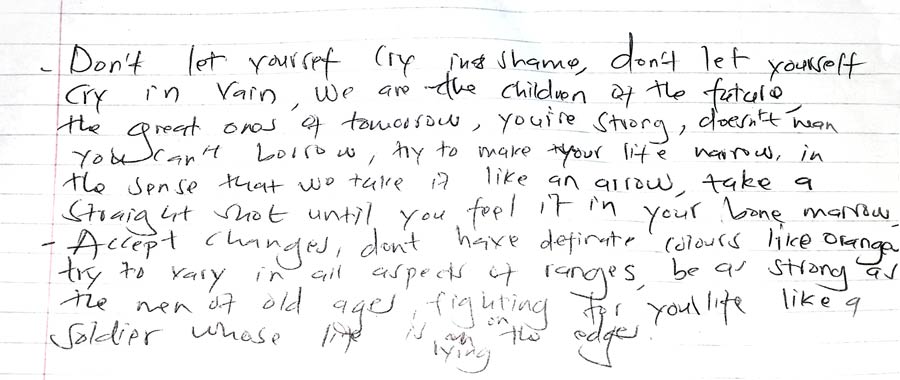

Adam Goldman ’94 also engaged multiple generations — but in song — at the elementary school, the homecoming tailgate, Hamilton Center for the Arts, and the Palace Theater.

Through his project, “I’d Rather Listen to a Bad Song,” the professional musician helped participants make protest songs. Goldman’s project was motivated by taking a famous quote by folk singer Phil Ochs and turning it on its head. Ochs famously once said: “I’d rather listen to a good song on the side of segregation than a bad song on the side of integration.” Goldman flipped it: “I’d rather listen to a bad song, as long as it was about something that I could get on board with,” he said.

Goldman set up a song-making booth at various locations, asked people what they wanted to protest, and then worked with them to develop lyrics. Then, they sang while he played a musical track.

Some of the songs were silly, like the first-graders who sang about their favorite games, including Hungry Hungry Hippos. Others addressed serious issues, like white privilege. “It was supposed to be fun, but also, if they were able to express something that was bothering them, [my] most idealistic version of [the project was] that conversations about uncomfortable things start,” Goldman said.

He recalled that, even as a Colgate student, he was making music and liked to push boundaries. “I did a rock opera here, with a couple of friends, called Glam: the Story of All the Young Dudes,” Goldman said mischievously. “It was about glam rock and we were very straightforward about what that scene was like, from what we read.”

“It’s a reminder that you need to exercise all the brain.”

Glam rockers made “different kinds of protest music — like David Bowie being a gender-bending polysexual back in the early ’70s,” Goldman explained. “And Prince in the ’80s, just being the way he was.”

Goldman added that he “was always more interested in frilly, high-gloss music.” After earning his master’s at California Institute of the Arts (where he met Machine Project’s Mark Allen), Goldman played in an electronic band called Fol Chen for 10 years. They released three albums under Sufjan Stevens’s label, Asthmatic Kitty. Goldman eventually burned out from touring and found more enjoyment in composing/producing. He now produces records for other artists from a studio in his house and is currently working with Andrew Bird, a solo musician who first gained fame with the band Squirrel Nut Zippers. “[Musicians] come to me if they want it to be a little bit weird; but I also understand the mechanics of pop music,” Goldman said.

He is also getting back to his filmmaking roots, which were inspired by Professor John Knecht at Colgate. Goldman is making a documentary about the history of luxury tourism. “It’s a reminder that you need to exercise all the brain,” he said.

Zoe Zhong ’17

Meaningful movement

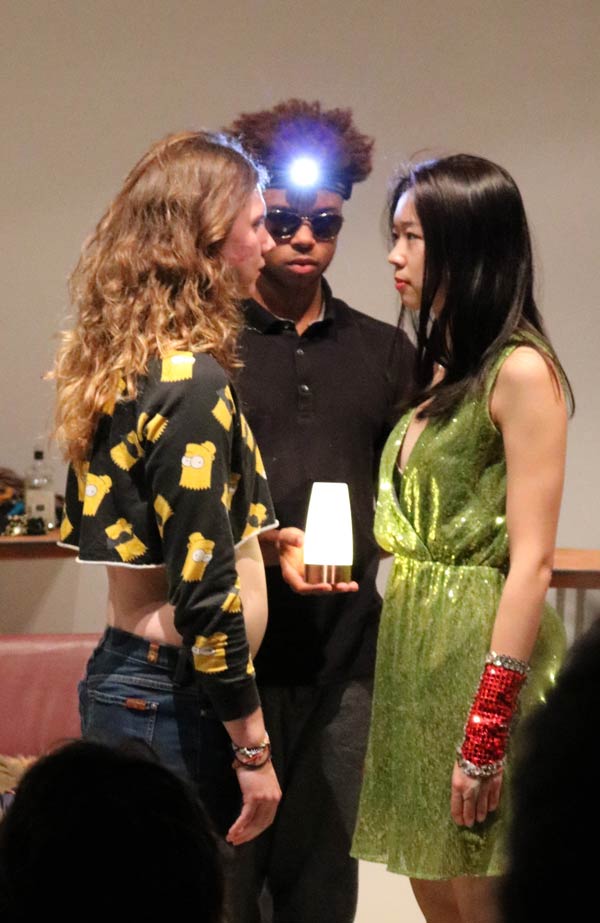

Hana van der Kolk first came to Colgate last March to meet with art department professors. When the professors learned of van der Kolk’s social justice performance work, they told her about the September 2014 campus sit-in sparked by race issues.

“I got the sense that people were still [affected by] that experience even though it happened in the fall,” said van der Kolk, explaining that it inspired her project proposal.

Students applied — seven were accepted — and van der Kolk spent three intensive weekends with them this fall. “I melded two projects from the past as a starting point and invited the students to specifically think about race, gender, and difference,” she said.

The first weekend, she invited activist Angelica Clarke to help her co-facilitate “a preparatory situation where we did a lot of work around conscious communication, responsibility around media intake, and discussions around power and privilege,” van der Kolk said. “Then we wove in movement exercises that would help the students embody those ideas.” The next weekend, the group practiced performance exercises and “skills [for] developing greater intimacy with themselves and each other.” And the third weekend, they “generated the performance from the material that had arisen the first two weekends.”

The students were initially “anxious about the level to which we would have to open up to each other, or the level of discomfort we were about to endure,” Sharon Ettinger ’18 said. However, through exercises and dialogue, they found unity, she added. “We opened up the space through [talking about] our personal backgrounds, childhood memories, pop-culture interests, and ultimately, our individual conceptions of privilege.”

Carmina Escobar, from Mexico City, gave “sonic massages.” She used the vibrations of her voice on different spots in recipients’ bodies and selected her pitches depending on their bone structures.

Van der Kolk said that the final performance “came from their own bodies, from various experiences of experimenting and improvising together.” She had also asked the students to write about their experiences around privilege, and to look for other writers who inspired them, so they planned some readings throughout.

“We opened up the space through [talking about] our personal backgrounds, childhood memories, pop-culture interests, and ultimately, our individual conceptions of privilege.”

During the final rehearsal days, student activists on campus were again speaking out — this time against sexual assault (see pg. 3). One of van der Kolk’s rehearsals was affected by a gathering in the chapel where survivors told their stories. “Two women in the group went to support their friends, and the rest of us ended up going to support them, too,” van der Kolk said. “The students kept apologizing [because it delayed rehearsal], but I told them that this is ultimately what this is about — having community so that we have the strength to speak truth to power.”

Van der Kolk taught the students how to use artistic practice as a way to work through issues. “We came together to simultaneously speak out and fully hear each other, finding solace in facing discomfort and thus tackling this discomfort in unity,” Ettinger said.

“They thought about their identities on campus, but more broadly, how they could articulate the concerns that they have as members of the community and some of the tensions that have surfaced,” Schwarzer explained. “[That experience] gave those students a significant engagement with ways of thinking about art as identifying and solving so much more than you could ever have hoped for.” It was also meant to be a learning experience for the audience, who joined in a group dialogue after the performance.

Godfrey added: “That was a great example of how art can have some real agency in helping to mediate and articulate these high-intensity issues in ways that make them accessible outside of language.”

Open-ended

Machine Project proved that sometimes art is intended to ask questions, not answer them.

“It opened my mind to other possibilities of the art world,” said Emily Wortmann ’19, one of Godfrey’s students. “Everybody just thinks of art as what you’d find in a gallery, but it can be so much more — it can be an interaction. And even if you didn’t think it was art, you had an interaction or experience that you otherwise never would have had.”

“As I told my students,” Godfrey said, “[the meaning of this] might not all come to you immediately, but let it sit there and it’ll be the kind of thing that all of us years from now will go, ‘Oh, remember that time?’”

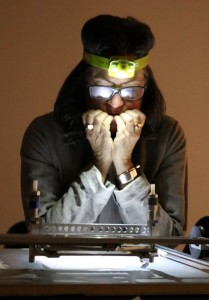

Photo of Chris Kallmyer by Andrew Daddio

Behind the Scene

How often do you have a chance to save the day with a broken metal utility handle? Strangely, that ended up being the case when I had the pleasure of working with artist Chris Kallmyer.

Kallmyer works with sound, exploring a participatory approach to making music using everyday objects. On the lawn outside of Persson Hall, he was testing a rake that he had modified by attaching a microphone to it. The raking would send vibrations up the bamboo tines and would be picked up by the microphones, which would then be processed through synthesizers, producing unique soundscapes correlating to each movement.

I shot a portrait of Kallmyer, as well as images of him raking up huge piles of leaves that would later be used for the performance. But, after less than 15 minutes, the wooden handle of the rake snapped where he had drilled the hole to mount the microphone. He wasn’t sure that it could be replaced because he had bought the last two bamboo rakes at the local hardware store.

I remembered that I had a metal utility handle in the corner of my garage. The plastic mount had broken, but it seemed like it would still attach to the rake with a clamp and screw. I went and got it for Kallmyer.

When I showed up that night to shoot the performance, Kallmyer had the metal handle firmly attached to the bamboo rake, and he informed me it was also a telescoping handle. The handle made it through the performance without a hitch. Because it was too large for airline travel, Kallmyer left it with the art department. As a side benefit, it can also be comfortably used by unbelievably tall individuals!

— Andrew Daddio, university photographer