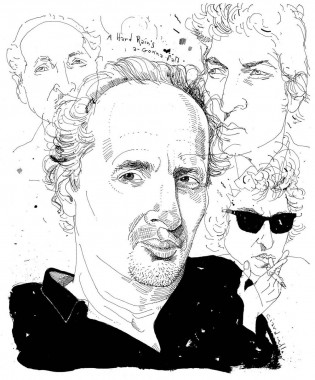

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello

With a pair of new books out this year — one a collection of his essays; the other, new poems — poet and English professor Peter Balakian unpacks, among other things, how language can, in his words, “ingest” the violence of history. The author of the New York Times–bestselling The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response and the prizewinning memoir Black Dog of Fate, Balakian has been called “the American conscience of the Armenian Genocide.” Last spring, he was invited to read and lecture at more than a dozen universities and made various media appearances including CNN and NPR’s All Things Considered in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of the 1915 slaughter of Armenians by the Turkish government. He received the 2012 Alice and Clifford Spendlove Prize in Social Justice, Diplomacy and Tolerance.

Excerpts from Vise and Shadow: Essays on the Lyric Imagination, Poetry, Art, and Culture trace his writerly sensibilities — first, their roots, and second, on the notion of poetry itself. Two poems from Ozone Journal embody that expression.

We were running wind sprints at the nearby grammar school, training for football, early, for the fanatics who “wanted it bad,” as coach said. It was late July, and in northern Jersey in dead summer, the humidity swells the windowsills, crabgrass wilts, any shirt sticks to you. The ground you run is dust, and you swallow it. After practice, we were dripping wet in the muggy air that was turning purple, walking in the hum of air conditioners on suburban streets, the water-pulsing sound of sprinklers on evening lawns. The dust was mud specks on our faces, and one of the older guys on the team asked me to come over to his house to pump iron. He was the best player on the team, and I was pleased to be asked. As we walked the quiet streets to his house, I was humming a song I couldn’t get out of my head, “Mr. Tambourine Man,” by The Byrds.

“It’s a Dylan song,” my friend said.

“Yeah,” I said.

“You know Dylan’s version?”

“Sure,” I said. Everyone knew it was a Dylan song. The DJs kept saying it was a Dylan song.

There was something gritty and earthy in it, something nervous and edgy.

I followed my friend into a dimly lit basement, linoleum floor, paneled walls. The bench press with big black Joe Weider disks on the bar in the center of the room. My friend turned on the air conditioner, tightened the collars on the weights, and put the needle down on a record. After a couple seconds of gravelly needle sound on plastic, a voice came out … came as a sinuous sound crawling into the air. It was quiet at first and gravelly, as if it were coming from the upper throat and nasal tunnels. There was something gritty and earthy in it, something nervous and edgy. This voice came out of the speaker and just hung there in that dense, humid air of a suburban basement. The voice hit me like broken glass under a tire, like metal scratching concrete. It wasn’t sweet; it was needling, like hitting nerve and skin, slightly liturgical — something minor key, the way the ghost notes wavered as they rose and fell. There was something ancient and primal in the voice, something raw and naked and intuitive, weirdly new. In that voice I would come to hear an estuary of traditions — bluesy, post-Guthrie Dust Bowl, folk, country and rock, Jewish cantoring and political edginess, social aberrance and poetic opacity. It was a transformative voice that carried with it some of the sediment of American culture. Some of those tonalities seemed familiar to me from the chanting and the drone modes I knew in the Armenian church on Sunday mornings and the cantoring rabbi at the bar mitzvahs of my friends.

The voice stung me as I stood there oblivious of my talented friend as he pumped the bar on the bench press with grunting vigor. Finally, he said to me: “Hey are you spotting for me or what?”

1965, Tenafly, New Jersey. Mostly playing for the coach. Pumping iron, being on the team. Studying as hard as needed. Dating girls in the progression of courtships, going steady, and breaking up. But mostly playing for the coach. Halfback one season, point guard another, shortstop another. More important than the girls, the camaraderie of the guys, inseparable on and off the field. The hours on the phone were split between talking with Debby or Arlene or Michele, or with Ed, Michael, Bill, or Brian, Ralph, or Tom. Talking, talking about nothing; just talking about songs and things that happened in a day or a class or on the field. This was suburbia, affluent, kind, white, full of love, or half-love, hypocrisy, fear, and repression.

The voice hit me like broken glass under a tire, like metal scratching concrete.

But news leaked through. The war was on TV. The war was someone’s brother who came back in a box in the next town. The war was the submerged anxiety of the unspoken. We knew it was waiting for us. We had ideas about jungles and swamps and people who didn’t look like us. We caught fleeting images in fuzzy color on the nightly news. VC, Nam, napalm, Gulf of Tonkin, McNamara — sound bites that floated through my head at night.

On the news we saw Dr. King in crowds, at podiums, in jail. We saw James Meredith trying to get in the front door of a university. We saw Negroes — men, women, and children — this was just before Black Power and Black Panthers. We watched Negroes in the South picketing, getting blasted by fire-hose water, getting mauled by dogs. We watched Muhammad Ali telling off America about the war and about racial equality. We watched his dance in the ring, his amazing hands….

In that strange mix of unknowing and sensing the world beyond our town, Dylan’s voice came like strange music. Between reading Romeo and Juliet, the history of battles at the Somme, and diagramming plays for Saturday’s game, Dylan’s voice snaked out of the nylon white-mesh speaker of my new RCA red-and-white vinyl record player (this was before stereos with speakers and amps and woofers). It wasn’t just a voice with music, it was words; not just words, but language, something that was connected in some indefinable way to what I was reading in school. Shakespeare, Homer, Hawthorne, Whitman, Dickinson. The Dylan words had fresh energy, passion, strange combinations of sensations. The songs told stories as ballads do, or sometimes as poems do, or sometimes as some fusion of the two….

I’m not sure whether I knew the word apocalyptic then. But ever since the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, ever since our Weekly Readers in fourth and fifth grade at Stillman School brought us images of Cuba and Russia, Laos and Vietnam as dangerous places of enemy force, I felt for the first time a sense of uncertainty about the order of things. I felt an undercurrent of anxiety that I couldn’t always shake off in the glow of a Yankees game or an episode of The Dick Clark Show or Leave It To Beaver. A feeling came over me at night as I lay in bed imagining the new hydrogen bomb, the radiant mushroom cloud rising into the sky, an image that had become an emblem of American power by the time I was 10, but an image that also meant the end of things.

A feeling came over me at night as I lay in bed imagining the new hydrogen bomb, the radiant mushroom cloud rising into the sky…

That undercurrent of anxiety was part of the mood of Freewheelin’, and I played it over and over, staring at the album cover with its whimsical image of Dylan in his scruffy jeans and winter jacket, arm around his girlfriend, Suzie Rutolo, as they walked a Greenwich Village street. The album moved with a narrative flow in which Dylan mixed slightly melancholic love ballads like “Girl from the North Country” and “Don’t Think Twice” with the quiet civil rights ballad, “Oxford Town,” and a diatribe against the military-industrial complex, “Masters of War,” a song that shook with the apocalyptic, and, finally, with “Blowin’ in the Wind” — which had become an anthem of 1960s liberation; had been covered by Peter, Paul, and Mary; and was so overplayed that it was, for me then, already a cliché.

I loved Dylan’s humor, which seemed like a blend of vaudevillian slapstick and playful, witty satire. The parodic “I Shall Be Free” kept playing in my brain as I sat in math class or through the long Armenian church service on Sunday morning. Dylan’s cement-mixing imagination lampooned sex, free love, celebrity, politics, advertising. With a Lenny Bruce–like verve, he poured acid on racism: “I flip the channel to number four / Out of the shower comes a football man / With a bottle of oil in his hand / It’s that greasy kid stuff / What I want to know, Mr. Football Man, is / What do you do about Willie Mays, Martin Luther King, Olatunji.” He had plucked the nerve of the color line in sports, but did he really know that Jim Brown had been denied the Heisman Trophy because he was black?

How did the sound of bells come over the cliffs

when the silks on the racks strangled the air —

before they turned to clouds of flowers?

That’s how the day came with its pomegranate seeds

and street screams; the priest who walked us last night

through the Armenian quarter was missing by noon.

The sky over the courtyard of Forty Martyrs Church

was frozen blue, ringing with AK-47s

and bells that my grandmother heard in another day.

We left our bags in the bedroom and wound

up in the boom-box café where workers in camouflage

slumped over coffee and sweet pistachios.

We rolled some parchment-thin pita

in our pockets, grabbed the cracked olives.

You ran into an empty building; I stayed

until the jeeps and soldiers left and some

of my Armenian friends came out with jars of water.

A tank was rusted out — some cameras were still hanging

from fences. Some fences rolled along the horizon.

Narrow screens do not allow for exact replication of poem format as originally published.

“A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” wound round and round my brain in the shower, in the football huddle, and in the morning when I was half asleep in homeroom as roll was called…. Those Hebraic, anaphoric catalogs and the tone of biblical prophecy put against an austere repetition of blues chords were beguiling, as were the images that were both contemporary and allegorical….

Dylan’s vision of poverty and racism took me out of Tenafly. This was not the poverty that we pretended not to see when we went into the city on weekends, as we drove through Spanish Harlem to get to my aunts’ apartments on Riverside Drive near Columbia, or through the Bronx or Queens. But poverty in the great middle of America, a place we called the breadbasket, the Great Plains, a place out there that was just a vague land to us East Coasters….

In his cantoring, minor key, which owed something to Jewish vocal tradition and something to blues, Dylan’s voice brought news of another America in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” a ballad (based on a true story) about a Negro hotel barmaid, a humble 51-year-old mother of 10 children who was bludgeoned to death by a 24-year-old rich, drunk, Maryland tobacco farmer. “William Zanzinger killed poor Hattie Carroll / With a cane that he twirled around his diamond ring finger / At a Baltimore hotel society gath’rin’ / And the cops were called in and his weapon took from him / As they rode him in custody down to the station / And booked William Zanzinger for first-degree murder.”

The way Dylan whined and dragged the name “Wil-lia-mm . . . Zan-zin-ger” was as exciting as it was unsettling — as if the meaning were so deep he had to wail it like a gospel singer hitting a note for the Lord. My obsession with phrases was part of me for as long as I could remember; words would get stuck in my head: toothpaste and cigarette ads, disc jockey rant, phrases from pop songs and college football cheers, weird things said around the house. All day and for days or months or more, some phrase that had some rhythmic energy, some odd force of syntax, music, and image would keep whipping or slowly rolling between my brain and ear. So the name Zan-zin-ger became a private mantra, one of those Dylan phrasings that hung around in my head all day — an encoded word that evoked racial injustice. As the song unfurled, Dylan’s voice grew into high-pitched emotion on certain phrases, against which the strummed chords were a quiet acoustic. An occasional mouthing of the harmonica creating that sense of pathos and then outrage, when in the end, justice is not delivered and the murderer is given a six-month sentence….

All day and for days or months or more, some phrase that had some rhythmic energy, some odd force of syntax, music, and image would keep whipping or slowly rolling between my brain and ear.

As I sank deeper and deeper into Dylan, I came to feel in ways that weren’t fully articulate to me yet, but still alive in me as instincts and intuitions, that my suburbia seemed to be about trying to blot the world out. Even in my family, which had inherited the dark legacy of survivors of the genocide of the Armenians in Turkey in 1915, the prevailing ethos on that past was one of repression and silence…. Because no one spoke about the Armenian past, that, too, became part of the conspiracy silence that pretended life was good and happy in America. History was better left to the dustbin of memory.

As I listened to these songs over and over through Christmas week of 1967, I thought about Dylan for the first time as a Jew. All I knew was that he was born Robert Allen Zimmerman in Duluth, a multiethnic Rust Belt city of the Great Lakes…. Whatever Dylan disguised with his new name and his pan-pop culture radical chic identity, he always had some ineffable Jewish sensibility and some Iron Range grit. Years later in his autobiography, Chronicles, he noted that his maternal grandmother with whom he was close — a woman who had only one leg, was a seamstress, and lived in Duluth — was from the town of Kagizman, “a town,” he wrote, “in Turkey near the Armenian border.” The family’s original name was Kirghiz, and his grandfather, too, had come from the same area, where they were “shoemakers and leather workers.” He confessed that his grandmother’s journey from Turkey across the Black Sea to Odessa and then to America was alluring to him, and how as a boy he identified with the mystery and outsiderhood of her past. Reading this in 2004, I found myself staring at the page unwilling to suspend my disbelief.

My obsession with phrases was part of me for as long as I could remember.

Kagizman — a place I knew well from my work on Armenia; it was an Armenian village, a very old Armenian village in the heart of historic Armenia not far from Armenia’s famous medieval city — Ani — today a walled city of ruins in the highlands of Turkey at the ravine on the Akhurian River, just a few feet from the Armenian border and a few hours by car from Mount Ararat, which is still Armenia’s national symbol even though it’s inside Turkey today. Given my own life and work, this small bit of family history that Dylan mentioned in passing but noted in precise detail, hit me in the strange way that odd historical coincidences do when they intersect on one’s own private map. I knew Dylan well enough from years of interviews and biographies to know he was a fibber and a mythmaker and liked to spin layers of exotica around himself. Was this bit of family history true? Dylan’s mother’s family — Jews from Armenia? Jews from a town that had not only been an ancient part of Armenia, but a place that endured destruction and massacre during the Armenian genocide. I wanted to ask Dylan face to face if it were so, and I regretted more than ever that I had been unable to attend the two dinners with him to which I had been invited several years earlier by my friend Jacques Levy, who had written Desire with Dylan and had also directed the Rolling Thunder Revue….

Between 1962 and 1967, in a five-year period, between the ages of 21 and 26, Dylan mined a wild array of cultural resources, pulling everything he could out of his imagination — mixing, mashing, cutting, and splicing, making wild collages like musical versions of Rauschenberg’s great combines…. His linguistic turgidness and his cultural and historical expansiveness owe something to an American literary tradition that includes Whitman, Hart Crane, Faulkner, and Ginsberg, and out of that wellspring he invented what I call literary rock — that fusion of music and language that embodied something of what it means, still, to be living in our age.

— from “Bob Dylan in Suburbia”

As carbon might be put under pressure to create a diamond, the vise grip of lyric language gives a poem or song a value and a legacy as a deep mine of knowledge and culture in which human thought and emotion, language, and insight intersect and mingle, and come together as distinctive, memorable aesthetic form….

In taking in violent events and traumatic aftermaths, poetry offers no answers, but it does offer meaning and insight — and that can be redemptive or, even [as 20th-century Polish poet Czeslaw] Milosz suggests, salvational. A poem allows clarity and imaginative depth in the face of forces that have sought to destroy natural and human order and, perhaps, what one might call the guideposts or ethics of civilized social order.

After Auschwitz, [critical theorist Theodor] Adorno sensed that there should be a new kind of poetry, as the violence of Auschwitz would have to prompt the human imagination to reconsider and reflect more deeply on human experience and the meaning of history, to change its relationship to the world. I believe that the kind of poems that ingest violence can have sacramental meanings. No matter how horrible the realities they embody, these poems give us an aftermath of consciousness that allows us to understand something — personal, intimate, social, collective — about the impact episodes of mass violence leave on the landscapes we inhabit.

In this way, the poem that ingests violence also provides us with a form for memory that captures something of the traumatic event that has passed. Poetry’s appeal to chant and prayer, song and psalm, whether oblique and symbolistic or plain and homily-like, returns us to the ancient, primary human voice that poems embody. And the poem, of course, catches the event of violence in its own music, in its peculiar qualities of rhythm, in the web of language-sound that syntax creates, so that a peculiar kind of language might get stuck in the ear as it gets spun in the brain. In the lyric memory that poetry can provide, the speech-tongue-voice of the poem leaves its imprint on a historical aftermath, and it becomes one of our truest records of history, as well as an enduring embodiment of knowledge.

— from “Ingesting Violence: the Poetry of Witness Problem”

Driving Route 20 to Syracuse past pastures of cows and falling silos

you feel the desert stillness near the refineries at the Syrian border.

Walking in fog on Mecox Bay, the long lines of squawking birds on shore,

you’re walking along Flinders Street Station, the flaring yellow stone and walls

of windows where your uncle landed after he fled a Turkish prison.

You walked all day along the Yarra, crossing the sculptural bridges with their

twisting steel,

the hollow sound of the didgeridoo like the flutes of Anatolia.

One road is paved with coins, another with razor blades and ripped condoms.

Walking the boardwalk in January past Atlantic City Hall, the rusted Deco

ticket sign, the waves black into white,

you smell the grilled cevapi in the Bacarija of Sarajevo,

and that street took you to the Jewish cemetery where the weeds grew over

the slabs and a mausoleum stood intact.

There was a trail of carnelian you followed in the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem

and picking up those stones now, you’re walking in the salt marsh on the

potato fields,

the day undercut by the flatness of the sky, the wide view of the Atlantic, the

cold spray.

Your uncle stashed silk and linen, lace and silver in a suitcase on a ship that

docked not far from here; the ship moved in and out of port for years, and

your uncle kept coming

and going, from Melbourne to London to Kolkata and back, never returning to

the Armenian village near the Black Sea.

The topaz ring you passed on in a silver shop in Aleppo appeared on Lexington

off 65th;

the shop owner, a young guy from Ivory Coast, shrugged when you told him you

had seen it

before; the shuffled dust of that street fills your throat and you remember how a

slew of

coins poured out of your pocket like a slinky near the ruined castle now a disco in

Thessaloniki where a young girl was stabbed under the strobe lights — lights that

lit the

sky that was the iridescent eye of a peacock in Larnaca at noon, when you walked

into the

church where Lazarus had come home to die and you forgot that Lazarus died

because the story was in one of your uncle’s books that were wrapped in

newspaper in a suitcase and

stashed under the seat of an old Ford, and when he got to the border

he left the car and walked the rest of the way, and when you pass the apartment

on 116th and Broadway — where your father grew up (though it’s a dorm now) —

that suitcase is buried in a closet under clothes, and when you walk past the

security guard

at the big glass entrance door, you’re walking through wet grass, clouds

clumped on a hillside, a subway station sliding into water.

Narrow screens do not allow for exact replication of poem format as originally published.