Charles Schwartz ’70, Kevin Strauss ’90, and Richard Steet ’94

Although their days in Hamilton were years apart, Richard Steet ’94, Charles Schwartz ’70, and Kevin Strauss ’90 found each other through their professions — and they’re now collaborating on a three-year $1.8 million grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation. They are studying neuron functioning in neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s and autism spectrum disorders by zeroing in on the chains of sugar molecules that adorn proteins and lipids.

Steet is an associate professor at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center at the University of Georgia in Athens, where the majority of the grant’s research will take place. He met Schwartz, the director of research at the Greenwood Genetic Center in Greenwood, S.C., nearly a decade ago while visiting colleagues at the center. Schwartz’s laboratory is focused on identifying the genes underlying intellectual disabilities, birth defects, and autism.

Steet and Schwartz decided to collaborate on a project identifying the genetic mutations responsible for “Salt & Pepper” syndrome, a rare neurological disorder named for the skin coloring resulting from alternating areas of too much and too little pigmentation. They found that the mutation disrupted an important biological process called glycosylation, where sugar (carbohydrate) molecules are attached to proteins or lipids during their biosynthesis.

Glycosylation is a different function of sugars than most people think, Steet explained. “We tend to think of sugars only as fuel for metabolism, but they have other essential functions in cells. When added to proteins and lipids, sugar chains impact their properties.” For example, the sugar chains on proteins help stabilize and protect them, ensuring that the protein can carry out its function in the cell.

By examining a type of stem cell derived from patients’ skin cells, Steet and his colleagues at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center have found interesting changes in glycosylation when you compare normal and diseased cells. With the new grant, they’re expanding their research into neurons, by coaxing the skin stem cells to turn into brain cells. These neurons will have all of the same genetic mutations as the patients, allowing the team to understand how mutations can affect glycosylation.

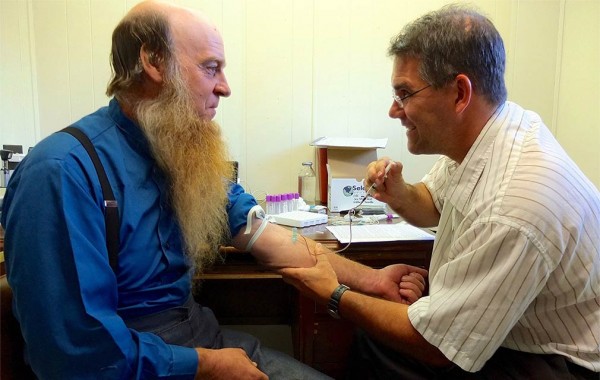

Strauss joined Steet on the project after the two met through another colleague. Strauss is medical director at the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pa., which diagnoses and treats genetic diseases in the Amish, who have particularly high rates of some gene mutations and diseases.

“Both [Schwartz and Strauss] have access to a large repository of cells from patients with neurological disorders,” Steet said. They will be providing the majority of the patient samples, while he will be introducing some of the genetic mutations into an animal model to further examine the effect of the gene changes on glycosylation.

There is also a therapeutic component to the grant. “One of the things we’re looking for is compounds that specifically affect glycosylation in neurons. These could potentially become therapies for the neurological diseases,” said Steet.

Already knowing that they both were Colgate alumni, Steet and Schwartz “realized when we were putting the grant application together that Kevin also had graduated from Colgate,” Steet explained.

The coincidence is remarkable, he added. Steet anticipates this is only the beginning. “I foresee that we will be collaborating beyond the scope of the grant for many years.”

— Allison Curley Marin ’04