The fraught history of the Bible in North America and how American Indian communities have grappled with it.

More than 500 years have passed since the European invasion of the Americas, lands that were not an unpopulated paradise, but rather homes to distinct peoples and their many cultures, languages, and technologies. As scholars have attempted to grapple with the legacy of colonialism, they’ve identified a number of tools the invading forces used to perpetrate their violent claiming of the land: firearms, large militaries, slavery, and disease. But equally important in the invasion was another form of conquest: the Christian Bible.

In a new paper, Christopher Vecsey, the Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of the humanities and Native American studies in Colgate’s Department of Religion, describes the holy text as “a weapon of spiritual conquest.” The twist, however, is that the sword has just as readily been turned back on the missionaries and other colonizers of American Indians.

Originally commissioned to write an entry for the forthcoming book, The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, Vecsey reviewed his decades’ worth of research on the subject and ended up writing something too long for the publication. Instead, the work found a home in the journal English Language Notes, and it offers a summary of the ideas Vecsey has explored throughout his career.

In the Beginning

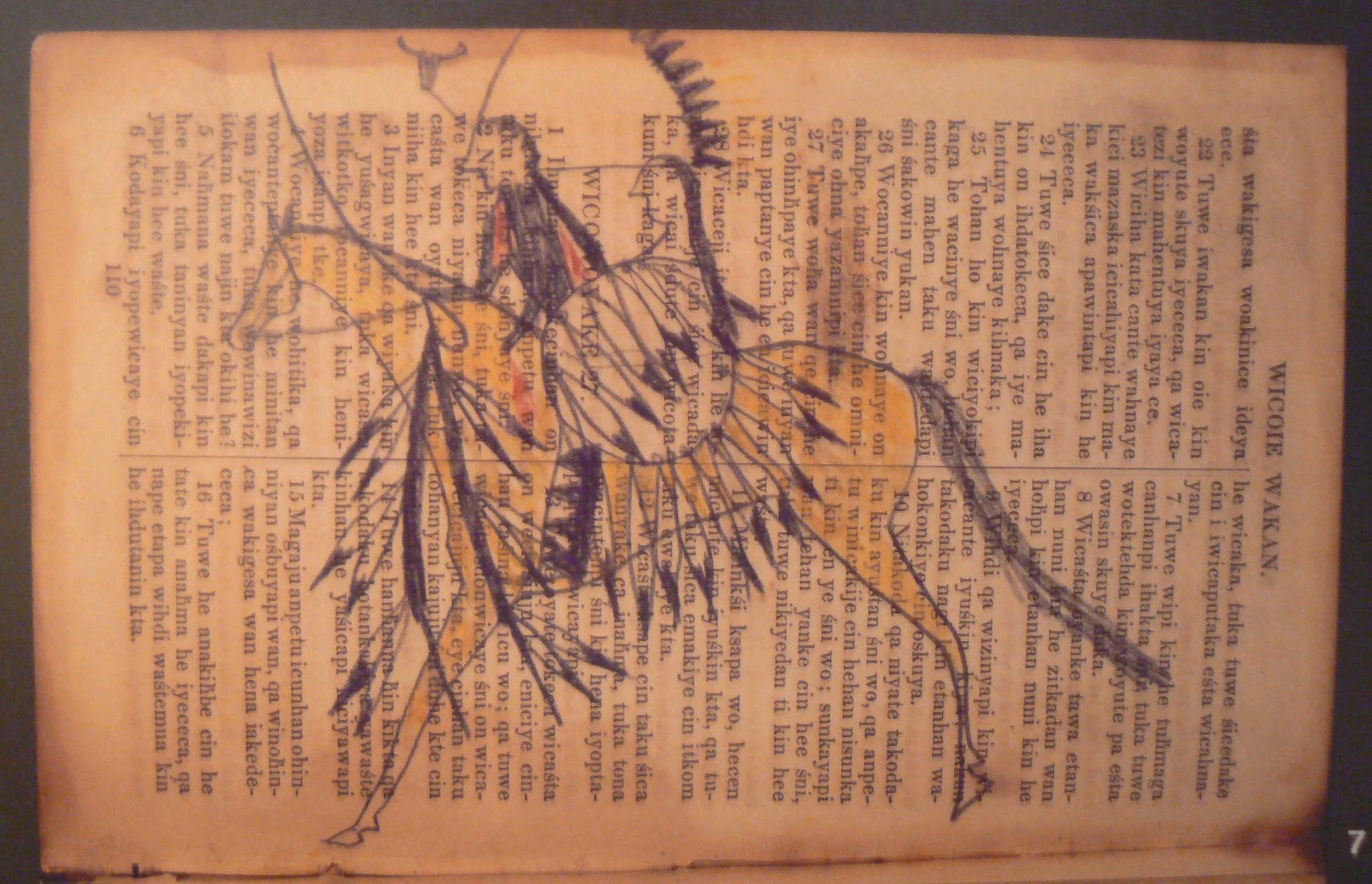

Early in the colonization process, missionaries began translating the Bible into many different American Indian languages. They often framed scripture not only through the lens of Christian charity and kindness, but also as condemnation of the Natives’ way of life. From the start, however, Native communities did more than simply imbibe the Word of God as proffered by Europeans. They used it to reflect for themselves on their experiences — and criticize the colonizing powers in return.

“Here’s the intellectual lesson,” Vecsey says. “When Christian Europeans introduced the Bible and wanted Native peoples to convert, little did they know that those people would adopt the Bible in ways the Europeans couldn’t have imagined. Their adoption was not passive. It was active.”

The Presbyterian Mohegan Samson Occom rejected categorizing Native peoples as a “cursed race,” Vecsey writes, and compared his Indigenous nation, the Brothertown Indians, “to the Israelites who would escape their ‘captivity’ and enter their own promised land.” Occom drew on numerous Bible passages to preach homilies on Christ’s promise of redemption, the importance of giving thanks, and the evils of slavery.

He was hardly the only Native American to transform these messages. Different communities incorporated Biblical characters into their own lore and myths. The Yaqui Catholics of southern Arizona went so far as to say the characters of the Old Testament were not from the Middle East, but had originally walked the desert of the Americas, as had Christ.

More recently, Native Americans have founded and joined Bible schools, such as the American Indian College in Phoenix. Some have become evangelicals, hoping to spread Biblical messages. The question among those groups is often how to interpret the Bible into Native practices, such as using drums as part of worship.

A Testament to Injustice

But just as there have been supporters of the religious text and its teachings, plenty of other Native people argue the Bible can never be used for the purposes of peace or justice since it was imposed on their communities through violence.

“We’re still in the colonial period; it has not gone away,” Vecsey says. “When contemporary Indian intellectuals talk about the colonized mind or colonizing knowledge, what they’re referring to is not just that Europeans came here and took natural resources and changed the environment and dislocated them. They’re also saying, ‘They put things in our mind that we can’t get out.’”

Vecsey cites the late Sioux academic Vine Deloria Jr., the author of Custer Died For Your Sins, as a particularly vocal detractor of Christian colonization.

Deloria wrote, “I have in my lifetime concluded that Christianity is the chief evil ever to have been loosed on the planet.” The son of clergy, Deloria felt strongly that the Christian religion could not be separated from the harm it had caused. “It has been said of missionaries that, when they arrived, they had only the Book and we had the land; now, we have the Book and they have the land,” Deloria declared.

That critique was echoed by Robert Warrior, an Osage scholar. “Do Native Americans and other Indigenous people dare trust the same god in their struggle for justice? Maybe, for once, we just have to listen to ourselves.”

Others have denounced the Doctrine of Discovery, the assertion that lands occupied by Europeans belonged to the colonial power that seized control of them, not the Native populations long in residence — an understanding among European governments that was given divine support by papal fiat and was even cited in decisions handed down by the United States Supreme Court.

Laying Claim to Eden

But how can such ideas be removed from the brain once they’ve taken root? How do individuals and communities go about the process of extricating themselves from Christianity when the influences of the Christian world are all around? Vecsey notes that prominent Native novelists like Leslie Silko, Linda Hogan, and Louise Erdrich all draw on Biblical imagery as a source of parody or allusion. It may be a form of subversion, but also shows how deeply ingrained those stories and beliefs remain.

Vecsey cites Cherokee scholar Laura E. Donaldson as calling for a new way forward by having Native people, once again, read the Bible on their own terms. She points specifically to Matthew 28:19-20: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.” The passage, Donaldson says, has been used to create “the most brutal system of conquest and exploitation the world has ever known.”

These arguments are nowhere near resolved, but this is a larger reflection of religious diffusion around the world. “The history of religion is the history of peoples being in touch with other peoples and sharing their deeply held beliefs and their cosmological stories,” Vecsey says. It may be a contentious, even bloody, process, especially in the context of colonialism, but it also shows the crucial importance of ideas from all participants — not just those who happen to be in power.