Professor Paul Humphrey explores the depiction of Afro-Caribbean religion in the world of comics

The sorcerer stands on the comics page, cape fluttering, eldritch energies crackling about his fingers. He’s a bridge between the realms of spirit and the mortal world, a master of strange and arcane magic. In civilian life, he’s a doctor. In costume, he’s hobnobbed with Avengers and X-Men in his capacity as Sorcerer Supreme. His name … is Jericho Drumm, Doctor Voodoo.

If you’re a comics reader — or just someone who enjoys superhero movies — you might have been expecting Doctor Strange. But while he hasn’t yet appeared in a massive blockbuster and has no A-list actor playing him, Doctor Voodoo embodies a fascinating and conflicted tradition at Marvel Comics: side characters that draw from Caribbean religions like Vodou. Such figures are the focus of new research by Assistant Professor of LGBTQ Studies Paul Humphrey. In a paper published in the latest edition of Studies in Comics, Humphrey traces the ways that American comics have depicted characters from Afro-Caribbean identities and religions.

Originally from the United Kingdom, Humphrey has spent much of his career studying the African-derived religions of the Caribbean. The most famous of these, Vodou, has long appeared in Hollywood and pulp literature as “Voodoo,” with imagery ranging from the exoticized to the blatantly racist. Santería, which blends Catholicism and West African spirituality, also tends to be cast as alien and slightly sinister. But Caribbean writers and artists are pushing back against such depictions. In a book that came out this year — Santería, Vodou, and Resistance in Caribbean Literature: Daughters of the Spirits — Humphrey argued that fiction from the region depicts Vodou and Santería as religions of resistance, standing against American neocolonialism, corruption, and Western Christianity.

While researching that book, Humphrey came across an independent comic called La Borinqueña, written by Colgate alumnus Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez ’93. It follows the adventures of a Puerto Rican girl who gains powers from the indigenous spirits of the island, enabling her to fight corruption and become the first Afro-Latina superhero. “I didn’t read comics as a kid. It was actually a brand-new topic for me,” Humphrey says. “So I delved further, and the article I wrote ended up looking at Marvel Comics in particular.”

©2018 Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez | www.la-borinquena.com

Since explicitly Afro-Caribbean characters aren’t common in Marvel comics, Humphrey focused on two in particular. The first, the Santerians, are a team of five superheroes created in 2005 by Marvel Editor in Chief Joe Quesada. Each member of the team has a code name and superpowers resembling those of the Santerian orishas — spirit deities — they embody. Their leader, Eleggua, for example, can understand all languages; Chango, orisha of flame and passion, can create electricity; Oshun, orisha of the rivers and seas, can control the liquids around her.

“Their role is to depict African-derived religions in the comic book world in a nuanced way, and to give people reading these comics from inside the United States a chance to see themselves represented,” Humphrey says. “The five members of the team have different skin tones, different powers, and different body types.” Readers didn’t get much of a chance to identify with them: the Santerians appeared just twice, in comic mini-series starring Daredevil and Spider-Man.

Doctor Voodoo — originally known as Brother Voodoo — got more of a chance to shine. Developed by Len Wein and Roy Thomas, and first drawn by artist Gene Colan, Jericho Drumm begins as a professional psychologist who’s summoned back to his native Haiti to help his cursed brother, a local priest of Vodou. After his brother dies, Drumm begins studying Vodou for himself — and eventually gets his soul joined with his brother’s ghost. While the character made regular feature appearances in the comics series Strange Tales, he wouldn’t get his own book until 2009, in a series called Doctor Voodoo: Avenger of the Supernatural. It was canceled after five issues.

Drumm is a complicated figure, Humphrey says. “He’s originally written in the very blaxploitation way — he’s bare-chested and is an imagined version of what a Haitian Vodou priest is going to be. So you’ve got a character who’s from Haiti and a whole series is focused on him.” Unfortunately, Humphrey says, even in Doctor Voodoo’s primary appearances, he has a tendency to be overshadowed. Doctor Strange shows up in early stories as the much more powerful and famous Sorcerer Supreme; when Drumm gains the role in his own series, Strange sticks around as a mentor and eventually gets the role back when Doctor Voodoo dies. (Comics being comics, he comes back eventually.)

This, Humphrey says, is pretty typical of a best-case scenario at Marvel. “The Doctor Voodoo series is well drawn, intelligent, and humorous in how it plays with the way Haitian Vodou works … but there’s still this narrative where Doctor Voodoo is never fully separated from his interactions with more established characters like Doctor Strange.”

Sometimes more famous characters get a touch of Afro-Caribbean flair attached to them, Humphrey says: the alien tree Groot, who got a somewhat unlikely star-turn in Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy films, gets an alternate origin story in the Marvel comic Guardians of Infinity, which identifies him with the great Ceiba trees. The trees are an important part of Puerto Rican indigenous practice, and have a role in Santería and Vodou as well.

This is the essence of the relationship between Afro-Caribbean identities and Marvel Comics, Humphrey notes: creators go out of their way to establish them as important, yet they never quite keep the spotlight. Part of the trouble is that even very respectfully depicted and drawn side characters are, ultimately, side characters, there to support the narratives of more marquee heroes like Spider-Man and Doctor Strange.

Independent comics not published by larger corporate entities like Marvel or DC Comics have picked up the slack and are an important part of Humphrey’s ongoing research.

“There’s definitely a narrative being written that says, ‘We’ve been represented in a certain way for a long time, and now we want to have a hand in representing ourselves,’” Humphrey says. “And if we work outside of the big titles like Marvel and DC, then there’s a possibility to do that.’”

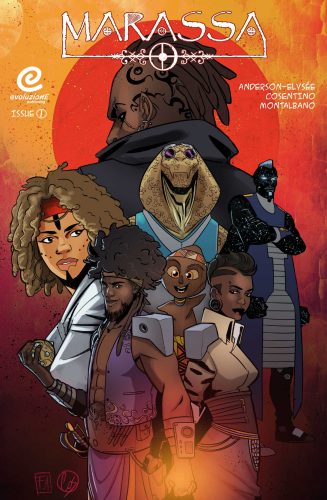

There’s the previously mentioned La Borinqueña and Greg Anderson-Elysée’s Is’nana the Were-spider and Marassa — the former can be likened to a Haitian retelling of a story about the trickster spider-god Anansi, and the latter is a future odyssey starring a pair of spirit twins, one of whom has a wooden mask baby as a sidekick. “These comics do deal with these issues of neocolonialism, slavery, neocolonial violence, gender and racial violence … they take these issues and imagine a different future based on Afro-Caribbean ideas, or a future in which Puerto Rico can have independence from the United States.”

Humphrey has proposed a spring course that will help students examine how comics allows us to read our own identities, with a focus on the identities of the Caribbean. “I think comics have long been a space in which folks dived in to try and find something they identify with, and then work through their own ideas: who am I, what do I represent, what can I be, what possibilities are there?”