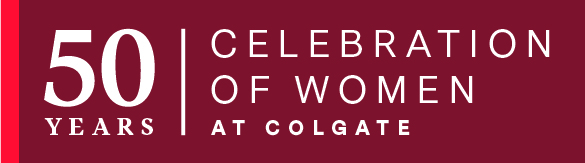

Female students brought new life to Colgate when the University went coed.

Four young women from Philadelphia, their parents, and a U-Haul stuffed with piles of clothing, record players, and a TV made their way north to Hamilton on Sept. 6, 1970.

“We had gone to an antique shop to buy fur coats, and we had all kinds of boots, because we knew how cold it was,” remembers Covette Rooney ’74. She and her twin sister, Cozette (Rooney) Ferron ’74, rode in the back seat of their parents’ baby blue Rambler, while their high school friends Angela Nolan-Cooper ’74 and Deborah (Booker) Matthews ’74 traveled separately with their parents.

This was the second time the four friends from Overbrook High School were coming to Colgate together. They’d visited the winter of their senior year, upon the invitation of Stephen Bradsher ’74. He was a recent Overbrook graduate who’d returned to his high school with another Colgate student to recruit women during a college fair.

“It took some convincing for our parents to allow us to take a trip to Colgate with these two guys [that winter],” Covette remembers.

“It was so pretty,” recalls Rae Scott-Jones ’74, whom they knew through church and invited to the pre-freshmen weekend. “There were icicles on the trees, like you see on Christmas cards. I had never seen that before in my life.”

“It was beautiful, and it was my top choice,” adds Matthews, who’d also applied to Penn State, Yale, and Indiana State. “It was a totally different experience that I felt I needed to be a part of.”

Come autumn, the five friends would join 10 other Black women who had been accepted as part of Colgate’s first coeducational class. They moved into their suites on the fourth floor of Center Stillman, above three other floors divided by gender and race.

The World Was Adjusting, and So Were They

In those early September days, “War” by Edwin Starr was the No. 1 single. More than 100 Vietnam veterans were marching in an 80-mile antiwar protest en route to a Labor Day peace rally in Valley Forge, Pa. (featured speakers would include John Kerry and Jane Fonda).

Closer to campus, Syracuse City Hall had just been taken over by women participating in the National Women’s Strike for Equality, sponsored by NOW. And Colgate students looked forward to Gloria Steinem’s coming visit as the Union Board Lecture Series’ first speaker of the semester.

The Class of 1974 comprised 132 women and 452 men. More than 600 women applied, and 235 were accepted. Of the 20 Black women who applied, 15 were accepted and they all enrolled.

“We came to Colgate because we knew we were going to get a good education,” Diane Ciccone ’74, P’10 said in an oral history interview. Having attended high school in West Winfield, N.Y., she had taken Colgate classes through a program for gifted students from area schools.

Ciccone was Cozette’s roommate who ended up forming a close friendship with the twins and their cohort. Although the idea of segregating students’ residential assignments by race sounds irrational today, “I felt comfortable because everyone on that floor looked like me,” Matthews says. “Coming from a predominantly Black high school, I could meet people who maybe shared the same experience I had.”

“I thought of it as a positive thing,” Scott-Jones adds. “I didn’t feel so foreign, so strange. I had a group of folks whom I knew, and it was going to be all right.”

The women also remember the University’s preparations — or the lack thereof, as some would say — for female students. The first semester, only one full-length mirror was available, in the bathroom, for 15 of them to share. Nolan-Cooper, for one, didn’t consider it a limitation. “We were very natural,” she says. “I don’t think any of us wore makeup.”

“They weren’t ready for us,” counters Matthews. “You had to make sure you showered around other people’s times because they didn’t have enough [facilities].” A number of women from the Class of 1974 — even those in other residence halls — also remember the urinals in their bathrooms, which were “decorated” with plastic rhododendron pots.

“On one hand, I could understand it because it had been all male,” Scott-Jones says. “But on the other hand, I thought, [they knew we] were coming, so get those bathrooms in order.”

After Thanksgiving break, the fourth floor Stillman women returned to find mirrors in their individual rooms. Over time, the University would begin to square up with its new identity.

The Long and the Short of It

Then-President Thomas Bartlett admits, “We did have a housing problem” — but he’s referring to the number of rooms, not their accoutrements. “Colgate didn’t have adequate housing for the students it already had, let alone to grow, but we made do the best we could.” That fall, the University started its final planning stages to build more housing units.

Bartlett, now 90, recalls his focus to be “the mechanics: housing arrangements, selection processes, getting the word out and applications in.” He also spent much of his early presidency traveling to alumni get-togethers, in order to discuss Colgate’s coeducation and alleviate concerns. “I would get some naïve questions,” he says. “[Once,] someone in the audience asked me, straight-faced, ‘How will the coeds hang their long gowns in the short closets?’ I was amused by that as I watched our very robust [female students] going to class, marching by in the snow in their army boots. The last thing I was worried about was how to deal with ‘these poor delicate females.’ I’d always been in coeducational institutions, and nothing like that was an issue.”

The University recruited Bartlett in 1969 when he was president of the American University in Cairo (Egypt). Having grown up in Oregon and been involved with four academic institutions that were all coeducational, Bartlett didn’t “understand this particular eastern phenomenon.” Indeed, when the possibility of Colgate going coed began to gain traction in 1963, a number of single-sex colleges in the East — including Dartmouth, Bowdoin, and Amherst — were still holding out.

A poll of Colgate faculty members showed that 91 of 108 were in favor of coeducation, according to a Nov. 4, 1964, Maroon article. John Rexine, associate professor of the classics, said the presence of women would raise classroom spirit, provide academic incentive for both sexes, and result in a heightened competitive standard. Huntington Terrell, associate professor of philosophy and religion, said, “All for it!” Herman Brautigam, also of philosophy and religion, commented that the idea “represents a certain amount of cultural lag.”

English professor Russell Spiers argued for the social advantages of coeducation: “It’s in the air today — inevitable — a good thing,” he told the Maroon. “Any young man with good red blood is going to be interested in some young thing with good red lips … there’s no good in trying to interrupt the process by segregating the sexes.”

Wanting to move the University in the direction of coeducation faster, Colgate’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors established an independent study group, according to Becoming Colgate by James Allen Smith ’70. The president at the time, Vincent Barnett, was displeased with the faculty’s action, so he created a separate committee.

As the University began weighing its options, two choices became apparent: Colgate could either restructure to become a coeducational institution or establish a coordinate women’s college, similar to the Brown/Pembroke model.

A Committee to Study Coeducation formed in 1965. The required cost for either model was a primary concern, but the committee considered the future of education and determined that coeducation was valuable for the academic experience as well as society in general. It initially favored a coordinate college model, Smith wrote in Becoming Colgate, but Board of Trustees Chairman Warren “Andy” Anderson “intervened to dismiss that idea outright, recommending that Colgate move toward a fully coeducational campus, and despite their skepticism, he was able to bring the board along.” (Read more about Anderson’s life in this issue’s “Flashback.”)

When Bartlett assumed his post as the new president, “we had virtually no endowment,” he recalls. “The thing that picked up the deficit was that Colgate had one of the most loyal and committed alumni bodies of any institution in the country,” Bartlett says.

Although many alumni were supportive of the move to coeducation, some were not. Consequently, Bartlett “spent a lot of time on an airplane” to ensure that alumni continued to support the changing institution.

Margaret (Digan) Sinclair ’74 remembers making fundraising calls: “Some of the alumni did not care for the fact that females were at the University,” she says. “You’d make calls to solicit them for money, and you’d have to convince them that you didn’t have horns. It helped [when I said] ‘I had a grandfather and a great-grandfather attend Colgate, 1890 and 1917.’”

Growing Pains

Providing facilities and extracurricular activities for women was not just a budgetary concern, Bartlett remembers, but also a process. As the student body began to include more women and the University gained a sense of what those women needed and wanted, Colgate would be better informed to expand its offerings.

“The numbers had to build up, and the response had to come,” he says. “Unless you have the money to do all of those things in advance, it becomes an action and reaction growing process, because that’s all you can afford.”

Leta Caplan Smith ’72, who came to Colgate from Skidmore on an exchange program in ’69, remembers running through the snow dripping wet after swimming. “There were no women’s locker rooms or changing areas,” she says, “so it was just ‘let your hair flow and freeze’” as you sprinted back to your room. By the fall of 1970, the University had converted the former sophomore locker room into a women’s locker room and “ordered hairdryers for feminine use,” according to the Sept. 6, 1970, Maroon.

The administration’s strategy of letting the new first-year women drive their own extracurriculars worked, to some extent. The Rooney twins and Matthews had been cheerleaders at Overbrook High, while Nolan-Cooper was a majorette, so they decided to form their own group at Colgate. They picked up their pom-poms and batons and proudly led the band. “If you could have seen the faces on the alumni [watching] these young Black women with big afros marching out on the field,” Nolan-Cooper says. “The students didn’t have any problems with it that I recall, but the alumni sure were taken aback.”

A few of the Philadelphia women also started an African dance troupe and produced a publication called Speak, Brother, Speak. “No matter what we asked, they never said no,” Nolan-Cooper says of the administration’s support.

“I don’t think the University was ever malicious. I think they just didn’t think some things through,” Gay Clark Jennings ’74, H’15 said in an oral history interview. She was on the first volleyball team, and one of the issues she remembered fighting for was equal medical coverage as an athlete.

Denise Cashmere ’74 was part of the group of women who went to the athletic director and said, “We want intercollegiate sports.” She’d played volleyball, softball, and basketball in high school, and she continued to play all three at Colgate. “The first two years we played as club status,” she said in an oral history interview. “We had whatever coach was around. We didn’t have uniforms. They brought out the men’s old basketball shirts, but that didn’t work because they went down to our knees and the scoop necks went almost down to our waists.” In her junior year, they hired a volleyball and basketball coach for the women and bought uniforms. “They ordered these little short cheerleader skirts,” she recalled. “Imagine dribbling a basketball while wearing a little short skirt.”

Of course, some women joined Colgate’s already established extracurriculars. Gloria Borger ’74, P’10 was one of the first women to join the Maroon staff and became the first female editor. Susan (Venarde) Mahoney ’73, P’12,’14, who transferred from Northwestern as a sophomore, was one of the first female DJs for WRCU. “I think they were open to having women DJs,” she says. “I just thought it would be really fun to choose what kind of music was being played on the radio… The whole Spear House was covered with shelves and shelves of albums. You could delve back into the jazz section because Robert Blackmore [’41, English professor and WRCU adviser] was there and he loved jazz. That aspect of it was really fun.”

The Weekenders

In a 2014 commencement speech, Borger joked about the University putting ironing boards in the women’s rooms. “Although, to this day, as my family can attest, I still have no idea what the ironing boards were for,” she said.

“We wore jeans and T-shirts, so I don’t know what we would have ironed,” Susan (Kornfeld) Kennedy ’74 adds. “It was the busloads of girls who came in from the girls’ schools who had everything ironed and looking pretty.”

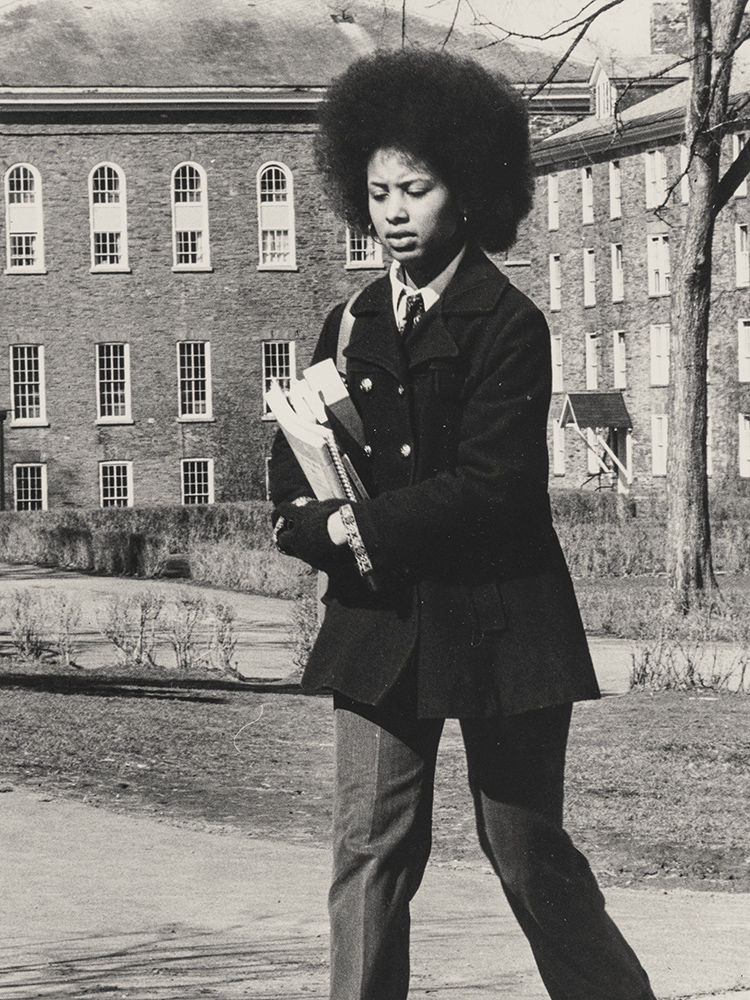

Kennedy is referring to the women from nearby colleges (such as Skidmore and Cazenovia) who came to Colgate on the weekends to socialize with the male students. Before Colgate’s first class of women, and even in the early years of coeducation, the men often vacated campus to travel to other schools for dates.

“Especially in the beginning, the older guys left on the weekends or they’d invite their off-campus girlfriends in,” Laura (Macomber) Weeks ’74 said in an oral history interview. “So there was a feeling of, ‘Hey, what about us?’”

“The one thing that bothered us most was party weekends — all these women from other colleges were bussed in,” Cashmere remembered. “The busses stopped [coming] as we became upperclassmen because there were more women on campus.”

The Colgate students did also date amongst themselves, of course. Kennedy, for example, ended up marrying an upperclassman, Paul Kennedy ’72. And Mahoney married her classmate, William Mahoney ’73.

Paul Kennedy was a Phi Psi, so Susan went to some of that fraternity’s parties. But she and others note that there were other fraternities women knew to avoid because of rape culture, excessive partying, and dangerous behavior in general. “It just scared me,” Kennedy says.

For the most part, “the Black women did not socialize with white men [at first],” according to Ciccone.

“The [Black] male students, the ones who came before us, were so protective of us,” Nolan-Cooper says. “We pretty much stayed in that little clique,” Matthews adds.

The cultural center (now ALANA), which was the result of campus protests at the end of the ’60s, was their social hub. “It was a great environment because we were able to cook foods that we were used to eating, like soul food,” Nolan-Cooper says. “We were able to bring African American jazz artists… And we brought Nikki Giovanni.”

Class Miss-Dissed

As a class, “the women are considered academically superior to the men,” Dean of Students Guy Martin said in the Sept. 6 Maroon. Martin had overseen the selection of the 1974 class as dean of admission the previous year. “While the mean SAT verbal score for entering men was 618, the mean score for women was 635. In the SAT math scoring, however, the men surpassed the women 639 to 620,” according to the Maroon. “And while one half of the women who applied qualified for [the] War Memorial Scholarship, only one out of every seven male students did so.”

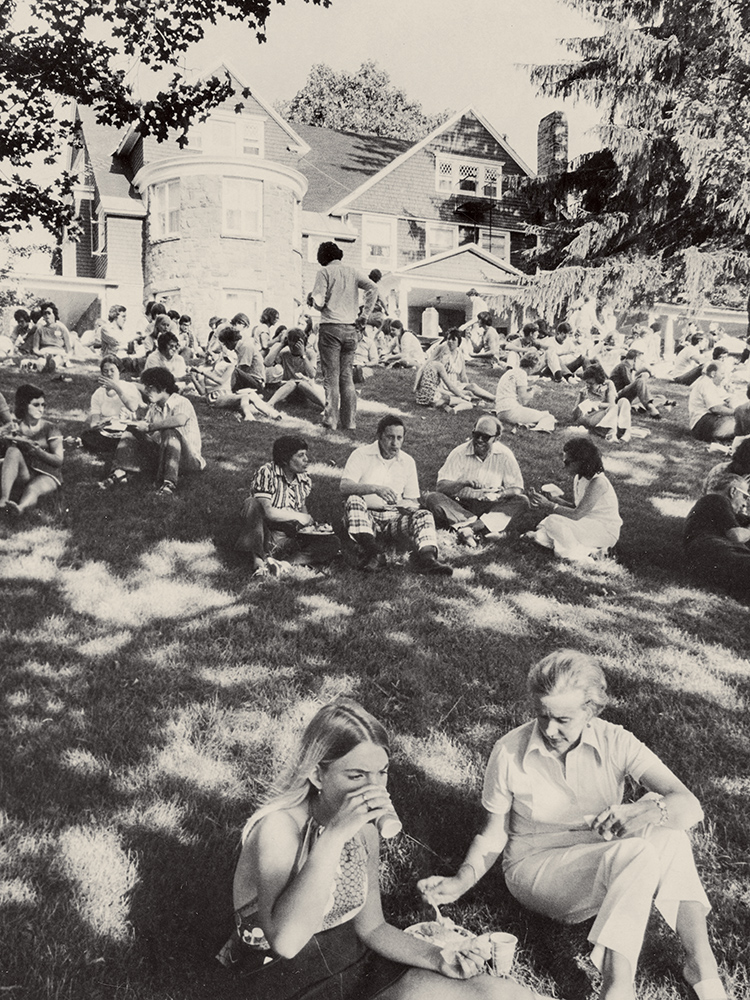

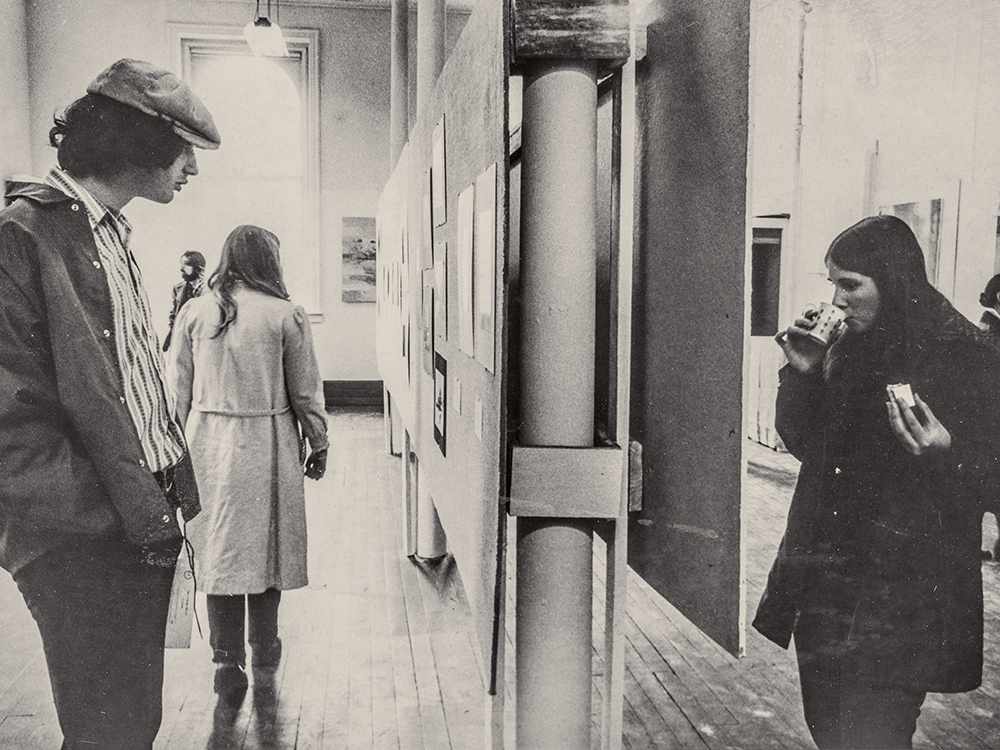

Despite the female students’ academic strength, their classroom experiences were not all positive, depending on the professor. “I sensed that some of the older male professors were not that happy to have women,” says Mahoney, who majored in art and art history and English.

From a faculty member’s perspective, James Clarke, professor of education and social science emeritus, remembers, “There were those who were old boys and wanted to keep it old boys, but they were few and far between.”

Jennings, a sociology major, remembered: “I had some great professors who were really attentive, and there wasn’t any difference between the men and women. Then there was a longtime history professor, who refused to call on women, so most women avoided his class. You could sit there an entire semester and he refused to acknowledge women’s presence because he was against coeducation.”

Carmela (McCain) Simmons ’74 said in an oral history interview that she took classes from a biology professor who was close to retiring, and “he thought women were idiots.” She’d been warned by her upperclassmen friends not to take his class, and “it was the lowest grade I ever got at Colgate.”

Several women interviewed report either receiving low grades or failing classes, which they believe was because of their gender, and in some cases, their race. “Even though I had gone to a small, [majority] white, rural high school and got exceptional grades, at Colgate, they just saw me as this Black girl who didn’t have the same intellectual capacity as the white students,” Ciccone said. “Either you were ignored or you were called upon to give the definitive answer on growing up Black.” As a political science major, she felt that certain professors treated her as though she didn’t belong in the department. “I had professors who were really wonderful, really saw me. But there were professors who [didn’t].”

Kennedy remembers being literally chased around the table by a well-known English professor. “His classes were really good,” she says, “but he had a reputation with the women of being a little handsy.” The sense among the women if they reported any of this behavior to the administration, she says, was that the response would be “Boys will be boys. That’s just how it is.”

On the other hand, [literature professor] Frederick Busch, Kennedy says, “was the best teacher I ever had at any level,” and she kept in contact with him until his death. “He wasn’t easy on me, but he guided me in a really loving way. My writing improved phenomenally, and I [used that skill] professionally in the rest of my career.”

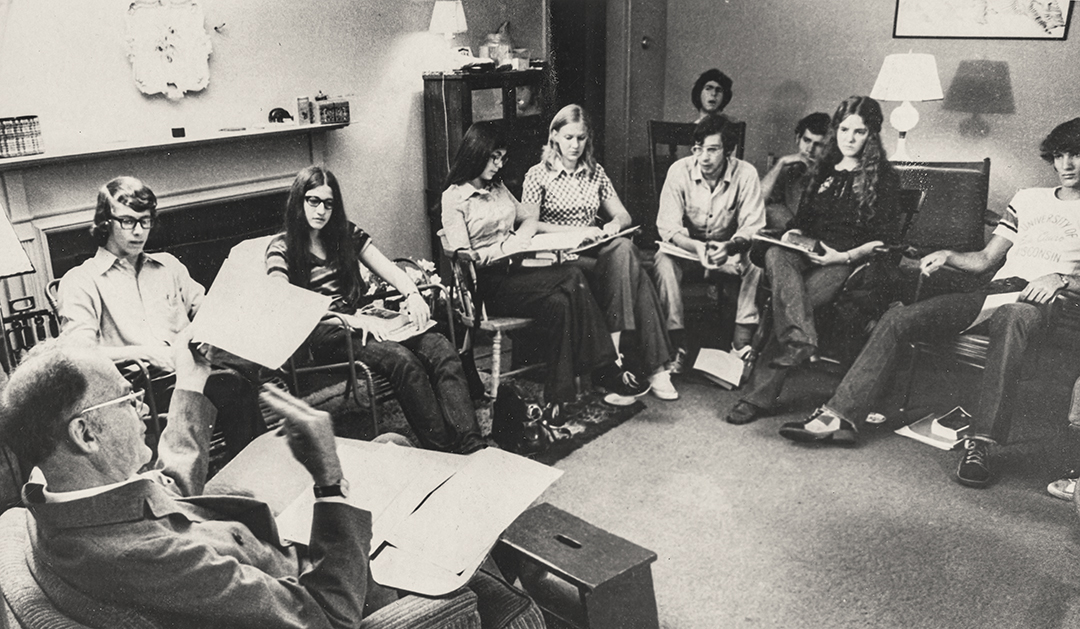

Numerous professors like Busch had a lifelong impact on their female students. Ferron entered Colgate wanting to become a teacher, but there was no educational studies major. “Professor Clarke,” she says, “saved me.” Hired in 1962, he’d been pushing for the program to be accredited as a major. Although “it started out very gradually,” and “not easily,” it did eventually come about, remembers Clarke, who is now 89 years old. He was also able to develop a teaching intern program through which Ferron and others could practice fieldwork at a local high school. Still today, Clarke believes in the importance of not just teacher training, but also giving students a well-rounded liberal arts education. “He was the one who really got me thinking outside of the box,” Ferron says. “He combined philosophy and stressed inclusiveness — creating a utopia where everyone benefits.”

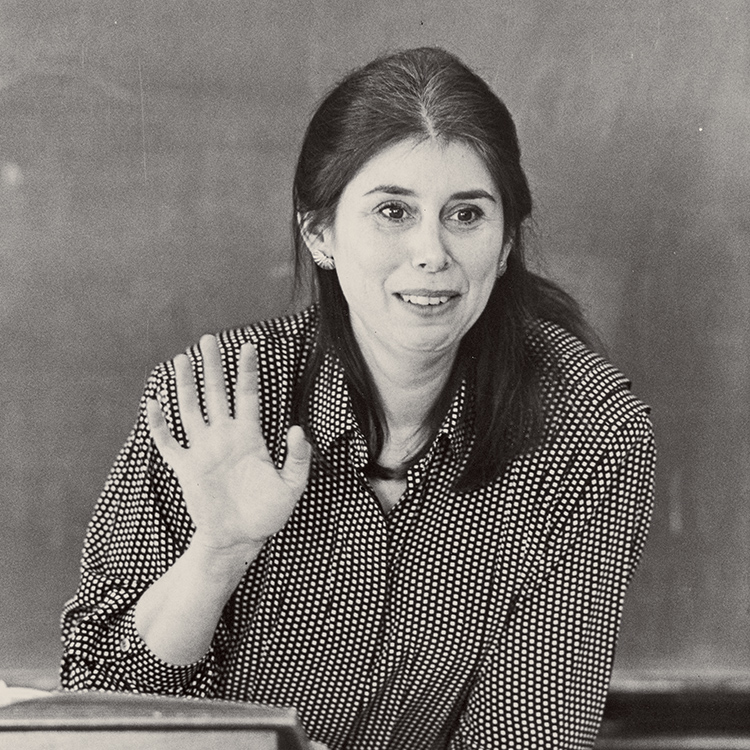

Meanwhile, Simmons recalled, philosophy and religion professor Jerry Balmuth heard students talking about Gloria Steinem, made a point to read Steinem’s work, and incorporated it into his next syllabus. “He said, ‘I want to know what you all are thinking about,’” Simmons said. “[And] Jane Pinchin was a wonderful English teacher who went out of her way to incorporate women’s studies into the English department.”

Sisterhood for Life

The alumnae from the Class of 1974 have different comfort levels with calling themselves “pioneers” or even “feminists.” But one thing they can agree on is, despite the ups and downs of their Colgate experiences, they relied on themselves — and each other — to thrive.

“I’m closer than sisters with some of these women,” Simmons said. “We went through a unique time in history…. We were very close and we still are.”

“We didn’t have mentors,” Ferron says, “so we mentored each other.” Her former professor, Clarke, comments on Ferron and her friends: “They were some of the first Black women who came to Colgate, so they had additional burdens, not so much because of prejudice but because when they walked around campus, they looked different than all the white guys. They were very good at adapting to that because they were fun and intelligent.”

Ciccone said that her Colgate experience prepared her for law school at Hofstra University: “I went from a predominantly male undergrad experience to a predominantly male graduate experience. I learned that I can’t get by on my merits. I had to be three times better, and I had to learn to accept that.” She went on to have a career in law and journalism, and she has served on both the Alumni Council and the University’s Board of Trustees.

Scott-Jones, Nolan-Cooper, and Rooney also went into law, while Matthews and Ferron had successful careers in education. They’ve all stayed friends over the years — standing up in each other’s weddings and becoming godmothers to some of their children — and they contributed to founding Colgate’s Alumni of Color group. “We’re still very connected,” Matthews says.

Laying the Groundwork

Professors Jane Pinchin, Wanda Warren Berry, and a handful of other female faculty members were pioneers in their own right — and they, too, faced uphill battles.

Pinchin and German professor Johanna Henry were the first two female full-time faculty members hired in the mid-’60s (until that point, all of the female faculty members were part time). “I was 23,” Pinchin recalled in an oral history interview. “Wherever I was, people knew who I was…. Being a woman on the faculty was a strangeness of that year.” She wryly remembers one of her first classes, a literature course that included Aristotle’s Poetics, and a student asking her about classical sensibility and homosexuality. “It was quite clear that what he was doing was seeing whether this teacher would fold, and it was so funny the way he presented it with such naivete,” she said. “It was a wonderful way to begin teaching, and in some ways, completely confidence building, not confidence destroying. Certainly, there was gender in the mix of that beginning.”

Berry was fighting to prove her intellectual capacity as soon as she arrived in Hamilton with her husband, Donald, in 1957 when he joined the faculty as assistant university chaplain and member of the Department of Philosophy and Religion. “I had just finished a three-year graduate theological degree at Yale, so I had had some experience with dominantly male institutions,” she wrote in her 2003 essay, “Hoping with Our Feet: Forty Years of Women at Colgate and Beyond.” Nevertheless, she added, “I soon learned that the small-town culture of the day was no more ready for professional women than was the college.” An example she shared in that essay “to epitomize the way things were when I first encountered Colgate,” was that she’d asked a religion and psychology professor to audit his course, because she had been working in that field. The professor obliged her, but midway through the term, the dean’s office sent her a message saying that as a woman, she was not supposed to be in the classroom. “It was as if I might open a floodgate — or somehow dilute the intellectual exchange,” Berry wrote.

In the fall of 1962, she and Gretchen Kreuter (whose husband was in the history department) were invited to teach sections of two core courses. The Kreuters did not stay at Colgate long, Berry noted, but Berry built a 40-year-career at the University. She is now professor of philosophy and religion emerita, and in 2018 (15 years after retiring) she was given Colgate’s AAUP Professor of the Year Award for her service on behalf of affirmative action.

The University hired two more women in the fall of 1970: Carol Bleser, associate professor of history, and Wanda Williamson, instructor of romance languages. The feeling among the female faculty members at the time was that they had no voice or power in the University’s decision making — not only to speak up for their own status but also as Colgate transitioned to coeducation.

Berry and others formed the Colgate-Hamilton Women’s Caucus because “we thought there should be a conscious and visible presence of women here when the first-years arrived,” she wrote in her essay. That academic year, the caucus sponsored programs, held discussions, and “asked to be on the agenda of the Committee on Admissions in order to challenge the fact that the plan for coeducation placed a quota on the presence of women in the student body.”

“The Year of the Woman” came about in 1974 when the faculty adopted an affirmative action policy. Five women were hired into tenure-stream faculty positions: Marilyn Thie (philosophy and religion), Margaret Maurer and Lynn Staley (English), Myra Smith (psychology), and Mary Bufwack (sociology and anthropology). By the end of that decade, 43 women (20%) taught at Colgate, but only 27 were full time. Berry noted that the tenuring process was slow over the next 20 years or so. Today, women make up approximately 46% of the faculty (at press time).

On the 13th of every month this academic year, the University will host an event celebrating the 50th anniversary of coeducation. The first event, in September, was a panel discussion moderated by Lee Woodruff ’82, H’07, P’13 and featured Tom Bartlett, Colgate’s 11th president; Jill Harsin, Thomas A. Bartlett Chair and Professor of history and director of the Division of Social Sciences; and Jane Pinchin, Thomas A. Bartlett Chair and Professor of English emerita. Visit colgate.edu/coeducation for the full list of events.